Trade War Two, China's supply subsidies, unintended consequences, and the mother of all bubbles

It has been a few days since my last post so there’s plenty to cover, starting with Donald Trump’s appointment of Peter Navarro and what it might mean for global trade.

Here comes trade war two

Oh boy. Last week Donald Trump announced that old mate Peter Navarro will be part of his new administration, in a newly created role of “Senior Counsellor for Trade and Manufacturing”.

Navarro, for those who don’t remember, is an economist with very heterodox views on trade. Released from prison around five months ago for lying to Congress, Navarro is a neo-mercantilist who formalised his thoughts through his 2007, 2009 and 2015 books The Coming China Wars, Manufacturing a Better Future for America, and Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World. He also produced a film in 2012 called Death by China, which is likely what influenced Trump’s thinking given he doesn’t read books.

The problem is that Navarro’s books are riddled with “arguments [that] are not based on economic analysis”, while the film is pure “propaganda”:

“…that ignores the essential realities of our maturing trade relationship with the world’s most populous nation. If the Trump administration accepts the distorted worldview put forward by this film and its author, the results cannot be good for citizens of either country.”

The US and China are already in the middle of a trade war. Indeed, just last week both nations escalated their dispute yet again:

“Beijing banned the export of several esoteric materials with high-tech and military applications, ordering retaliation after President Joe Biden imposed more curbs on China’s access to vital components for chips and AI.”

If Navarro is advising Trump for another term, expect tensions to ramp up again next year. Proponents might claim that it’s all part of a plan to “escalate to de-escalate”, and trade will be freer once Trump has made deals with everyone. But the fact that most of Trump 1.0’s tariffs are still in place or have been broadened under Biden makes me sceptical.

To be clear, the tariffs in and of themselves won’t destroy the US economy, which gets away with many more shenanigans than does Australia because of its size. For example, the Tax Foundation estimates the cost of Trump’s 2018/19 tariffs at around 0.2% of GDP, which is about $55 billion in an economy of over $27 trillion.

There are many costlier policies passed all the time in the US with far less hysteria. For instance, the Council of Economic Advisers estimated that emissions standard regulations for vehicles costs the economy 0.3% of GDP each year. For reference, that policy is what the Albanese government based its own version on and tried to gaslight us all into supporting with some dodgy modelling.

My biggest gripe with Trump’s tariffs is that they will increasingly isolate China and other countries. Remember Russia, which spent a decade “rebalancing” its economy towards self-sufficiency to “give it more freedom in international affairs” after being burned by falling oil prices and sanctions?

Ultimately, the less globally connected China becomes, the lower the economic and political costs Xi Jinping (or a future leader) will have to consider when deciding whether to start a conflict. By continuously talking about the threat of China, and responding by increasingly isolating China, the US risks setting in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Note that the same argument applies to the US; being reliant on, say, semiconductors out of somewhere like Taiwan also changes the calculus for a US President who might be considering aggression. If everything deemed critical for war is ‘onshored’, it reduces the costs of the decision to go to war.

Scale, China style

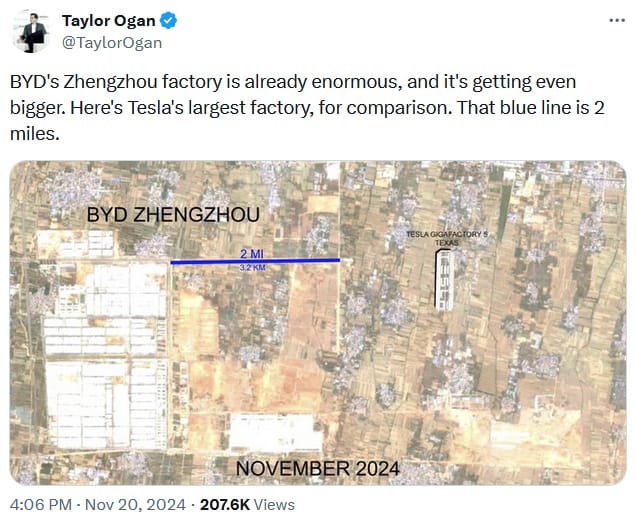

China can’t produce everything. If it makes all the world’s cars, it won’t have the people and capital to produce myriad other goods and services. But boy, is it ever good at making cars:

That sort of scale is how manufacturers like BYD are able to produce large quantities of high quality vehicles at competitive prices.

Is it a good use of resources? It’s tough to say; the Chinese government has sunk considerable sums into pushing its auto sector, which comes with the opportunity costs of exchanges that never took place. Perhaps China’s auto sector would have been half as big, but several other industries would have taken off if the government hadn’t redirected capital and bid labour away from them as part of its auto favouritism.

The Chinese government isn’t some omniscient being. It also directed capital into building a lot of cities that no one moved into, hundreds of kilometres of high speed rail that no one uses, and huge bridges in the middle of nowhere. As podcaster Dwarkesh Patel recently surmised:

“We subsidise demand and restrict supply. They [China] subsidise supply and restrict demand.”

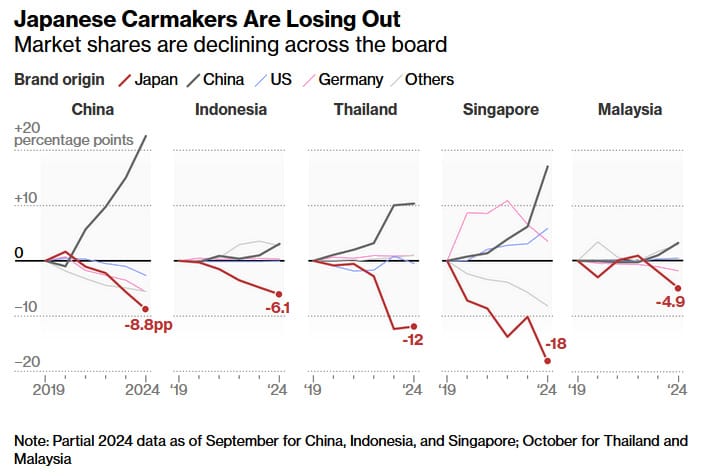

The good news is that surplus cars can be exported, so foreigners like us stand to benefit from BYD’s scale and the Chinese government’s allocation of resources away from its most productive uses. The losers will be incumbents who don’t adapt:

“As a group, Japanese carmakers have been slow to shift to fully electric vehicles. That could cost them dearly as they fall further behind in an industry where winners are being minted based on cutting-edge battery technology and smart software.”

We should be thankful for China’s over-investment in green tech like EVs and solar, because it allows us to reduce our carbon emissions at a cost well below what we would have had to pay otherwise.

The Greens don’t get it

The Greens have so many bad policies that it’s almost not worth covering them all. But given that there’s a reasonable chance they form the next government with Labor in some kind of “power sharing” deal, when they announce something, it’s worth at least listening. Especially if it’s something that might appeal to Labor politicians, such as this:

“The policy would force banks to limit the interest rate they offer to first home buyers at just 1 per cent more than the cash rate.

Greens treasury spokesman Senator Nick McKim said the major banks were ‘crushing mortgage holders’.

‘They are currently making billions of dollars in profits ripping off struggling mortgage holders by overcharging them on their mortgage,’ he said.”

First of all, the premise is wrong. The banks make billions of dollars in profits but their profitability is nothing out of the ordinary:

Eye balling that chart suggests return on equity of around 12%, which is low – companies should be aiming for something more like 15% to 20%. But as boring intermediaries, profitability should be a bit lower in the banking sector, especially given their effective oligopoly licence from the government (e.g. implicit bailout guarantee) and systemic importance. In the US, bank profitability is a similar 12.5%.

So, what might happen if mortgage rates for first home buyers are capped at 1% above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) cash rate? There are a few possibilities:

- The risk/reward ratio for a bank of issuing a mortgage to first home buyers will change, forcing banks to raise their standards, with those at the margin (likely the least well-off) now unable to secure financing from a major bank.

- Major banks will charge fees to make up for the smaller margins and preserve their profitability, as happened when mortgage rates went negative in certain European countries.

As JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon once said in response to these sort of regulations:

“If you’re a restaurant and you can’t charge for the soda, you’re going to charge more for the burger. Over time, it will all be repriced into the business.”

There is no free lunch, and there will be unintended consequences that, depending on the forms it takes, may well be worse than the action they’re trying to prevent.

The mother of all bubbles?

A recent article in the Financial Times (FT) suggested that “American exceptionalism” has been overbought, and may well end in tears:

“On indices that weight stocks equally regardless of size and correct for the domination of Big Tech, the US has outperformed the rest of the world by more than four to one since 2009.

…

Talk of bubbles in tech or AI, or in investment strategies focused on growth and momentum, obscures the mother of all bubbles in US markets. Thoroughly dominating the mind space of global investors, America is over-owned, overvalued and overhyped to a degree never seen before.”

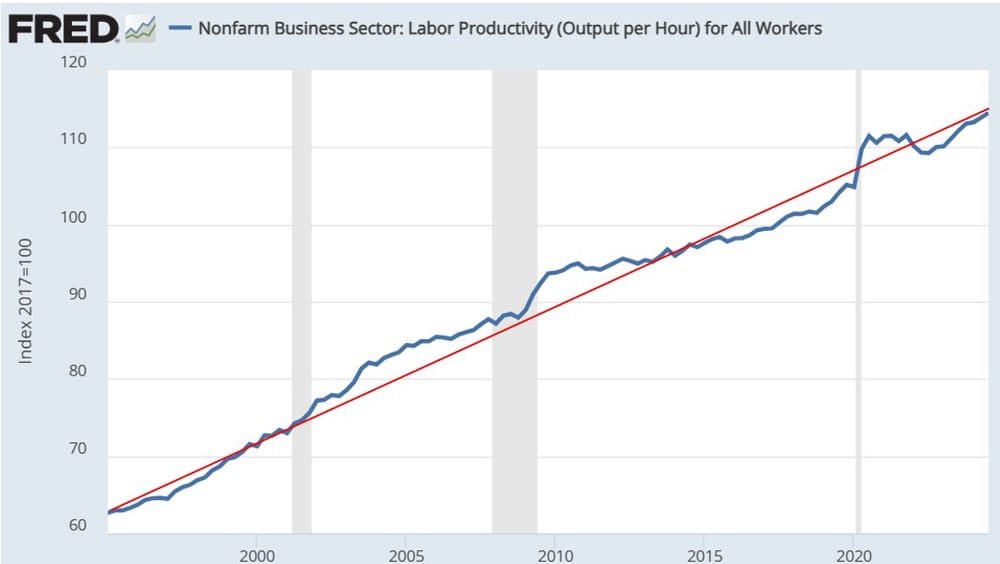

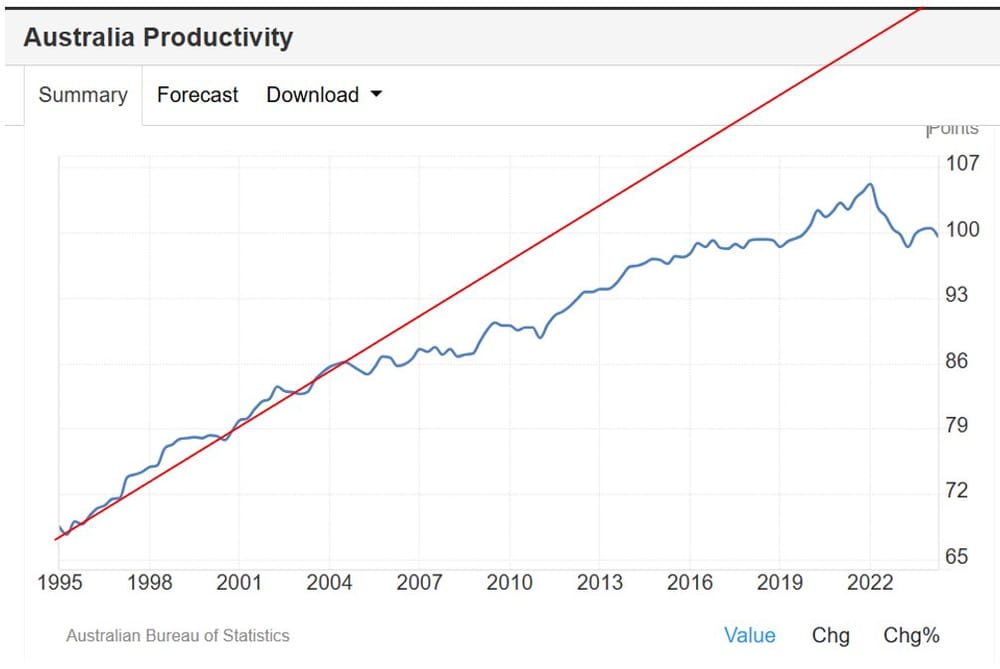

I don’t pretend to know if US markets are a bubble or not. All I’ll say is that in the long run, productivity is everything, and the US has been a world leader on that front for decades. Over time it adds up, and explains at least part of why US markets continue to outperform the rest of the developed world:

“All told the accumulated productivity difference between the US and the rest of the developed world in the last couple decades in level terms adds up to 20%+ in some cases. That’s a huge accumulated difference in terms of the value of output achieved in one economy vs. another.”

Capital has a way of flowing to where it will be most productive, and unless other countries get their chainsaws out and meaningfully reform their economies, then more often than not that’s the US.

Bubble, or just one of the only remaining markets in the world where your capital is secure from expropriation, and productivity – which helps boost corporate incomes – is still growing? Clearly markets expect “American exceptionalism” to continue, which explains why American assets are more highly valued than those elsewhere (expected productivity is capitalised into values today).

Whether markets are correct is another question, but neither I – nor the author of the FT piece – can know. All I’ll say is that betting against American exceptionalism continuing has been a losing bet for many decades.

Fun fact

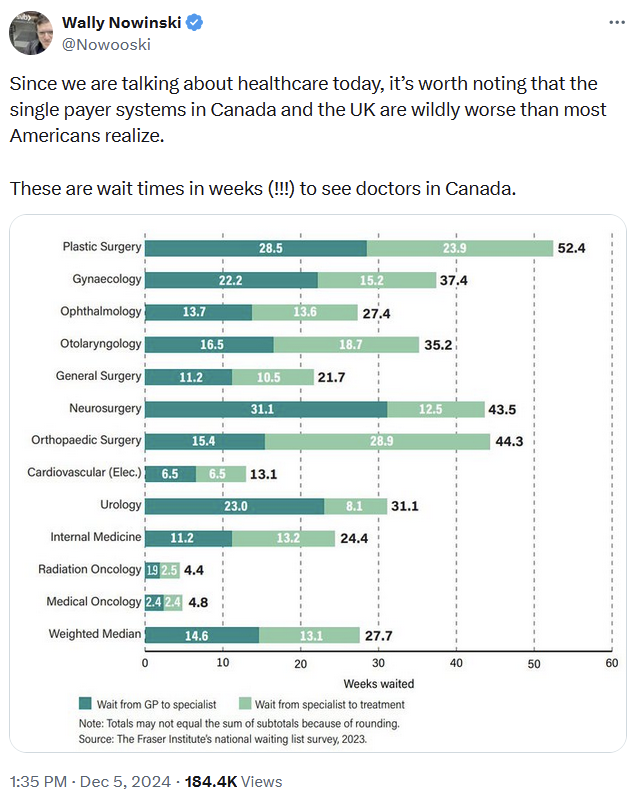

When something is “free”, the price is set too low and demand can overwhelm supply as taxpayers don’t have an infinite money tree to pay for it all. That means it gets rationed, so you also pay with your time:

Further reading

- It’s a bad time to be an incumbent politician: France’s parliament voted down Prime Minister Michel Barnier’s government, the first time it has done so since 1962.

- Still one France, " a recent Toluna Harris Interactive poll for RTL broadcaster showed 64 per cent of voters want Macron to quit". Under the French constitution, two thirds of politicians would have to agree that Macron “has gravely failed in his role” to remove him. The earliest another parliamentary election can be held is July 2025.

- The French crisis was brought about after an “attempt to bring the budget deficit down from 6.4% to 5%, which required a combination of tax rises and spending cuts”.

- The strength of democracy is that it facilitates the peaceful transfer of power between groups of elites. South Korea came perilously close to losing that strength, only barely avoiding a military coup: “Armed troops arrived at the National Assembly past midnight, clashing with lawmakers and legislative aides. It certainly looks like Yoon was trying to arrest his opposition in the National Assembly before they could vote to lift the order—his theory of the case, after all, was that they were ‘anti-state forces’.”

- Incidentally, South Korea’s declining birth rates and dire lack of workers has made it the first country in the world “to have replaced 10% of its workforce with robots”.

- Analysis of 30 pro-natal policies found that they “yielded a range of $50,000 to $2 million in extra spending per extra baby, median estimate around $400k”. Food for thought given all the discussion about immigration and Australia’s low fertility rates.

- Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai said that in terms of training AI, the “low-hanging fruit is gone”. But don’t make the same mistake economist Paul Krugman did with the internet and underestimate its significance: just because progress will inevitably slow doesn’t mean AI won’t usher in a productivity wave as people discover new applications and products.

- Trains can make economic sense when you have density and the distance between two places is too far too drive but too short to fly.

- Most people like working from home and are willing to take less monetary compensation to do so. If you want more people in the office but don’t want to pay them more, then they’re going to quit: “Academics from American and Chinese universities interrogated the job vacancy data of 54 S&P 500 firms and the employment histories of 3 million tech and finance workers on LinkedIn, and found staff turnover increased by an average of 14 per cent after firms introduced return-to-office (RTO) mandates.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!