Unpacking Australia's per capita recession

It’s national accounts day today, which is why you would have seen plenty of Treasurer Chalmers on the media circuit, pointing fingers in all directions except his own:

“With all this global uncertainty on top of the impact of rate rises which are smashing the economy it would be no surprise at all if the national accounts on Wednesday show growth is soft and subdued.

We anticipated a soft economy at Budget time and that’s what most economists now expect to see in these new numbers for the June quarter.

We are striking all the right balances between a primary focus on inflation and understanding the pressures on people in an economy already being hammered by higher interest rates and global volatility.”

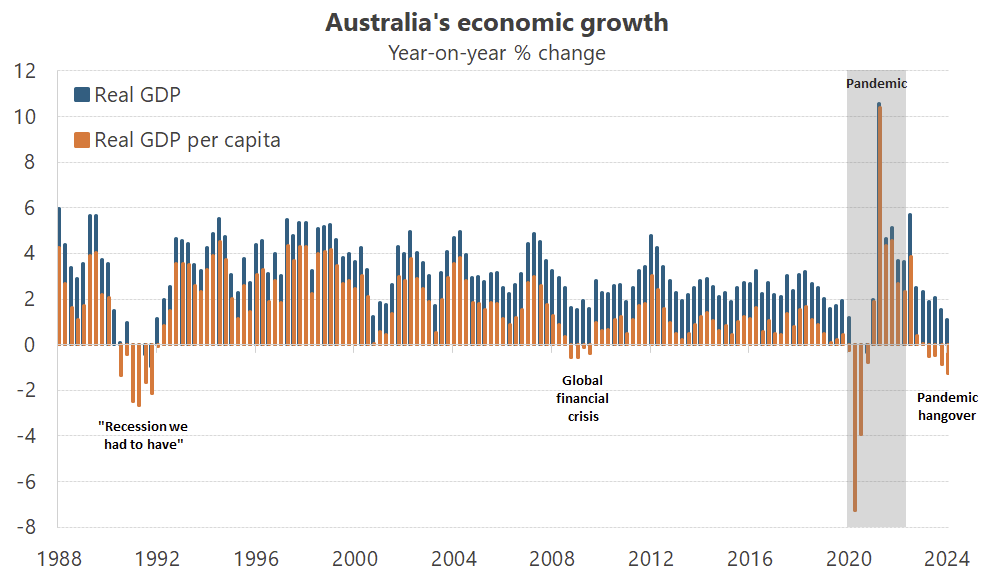

The June quarter national accounts will probably show that real GDP per person contracted for a fifth consecutive quarter, officially making the current period Australia’s worst and longest per capita recession since the 1990-91 “recession we had to have” (excluding the pandemic).

We’re not in a technical recession (GDP contracting over two consecutive quarters) largely because population growth and " strength in public demand" are keeping total activity churning along. But even that looks set to have weakened in the June quarter to around 1% growth from a year ago, according to Bloomberg.

Chalmers isn’t entirely to blame for the state of the economy. When the previous Coalition government and the states closed their borders, locked us down, and enforced social distancing, they reduced economic activity and paid for it with debt, much of which was bought (electronically printed) by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). That boosted demand and reduced the value of the currency relative to goods and services, causing the inflation.

As a recent paper concluded, supply chain issues were only a secondary factor (in that they constrained economic activity), with the post-pandemic inflation “predominantly driven by unexpectedly strong demand forces”, i.e. excessive fiscal and monetary policy.

Once set in motion, an aggressive attempt by the central bank to rein it back in would have “severely hampered an already anaemic recovery”.

So, a lot of the damage was baked in before Chalmers took office. Indeed, one reason this cost-of-living crisis feels so bad is because we had it so good for a couple of years. It may have all been an illusion, but that doesn’t change the fact that returning to a more sustainable path was always going to be painful; bouts of inflation always end up with prolonged reversals of the inflationary trend, which is costly.

A painful reversion

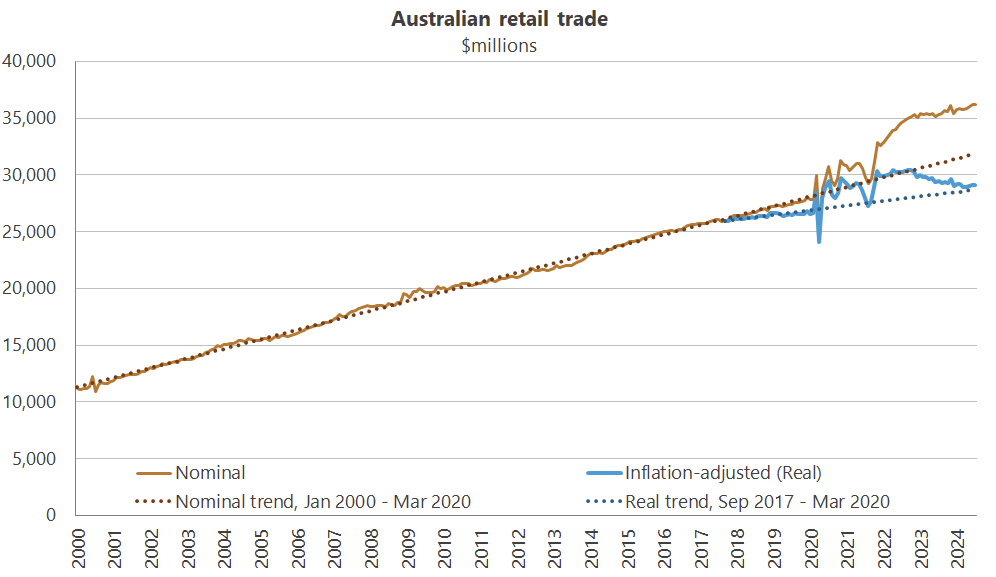

A look at last week’s retail turnover figures show that after a considerable increase in household’s real purchasing power, sales are now back to where they were before the pandemic:

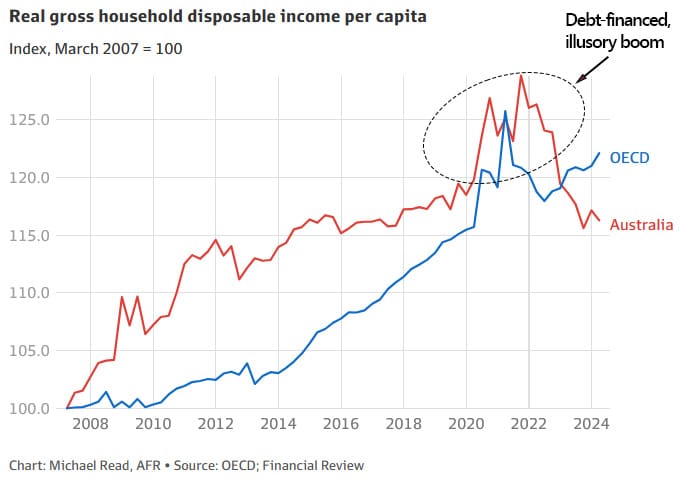

The story is even worse for incomes. We didn’t get any wealthier from all the debt-financed handouts during the pandemic while also working fewer hours; there was no miraculous surge in productivity that led to a sustained increase in real purchasing power.

No, incomes increased during the pandemic because the benefits of debt-driven inflation happen right away, while the costs take a while to be realised. Eventually they had to, and now they’re below the pre-pandemic trend as interest rates take their toll:

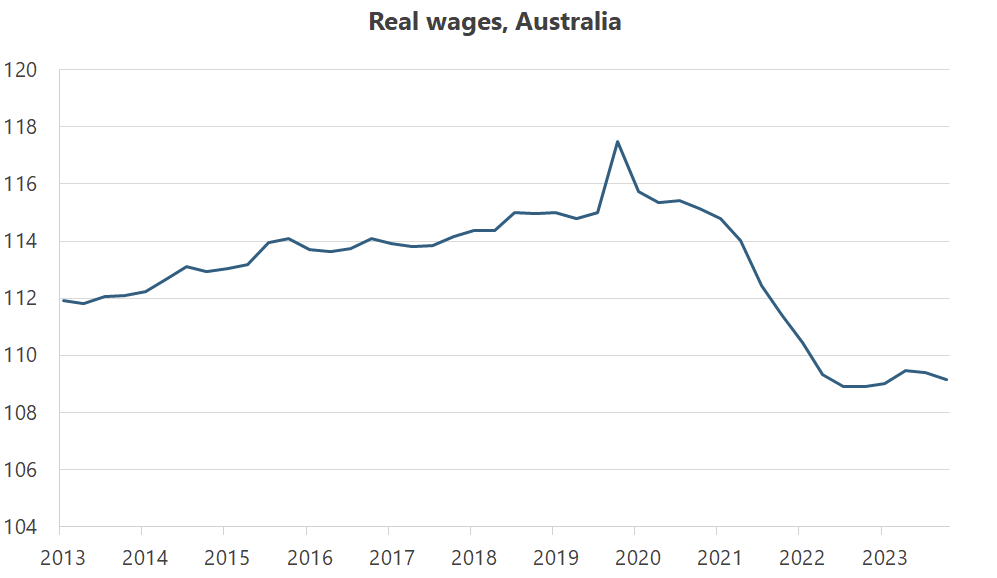

The good news is that real wages have at least stopped falling. But until they start meaningfully growing again, it’s cold comfort telling people that ‘hey, what you lost is very, very slowly being returned to you’.

Wage Price Index deflated by the Consumer Price Index.

Wage Price Index deflated by the Consumer Price Index.

If unemployment starts to rise – as it might in an economy with company profits falling and where the public sector has been responsible for creating half of all new jobs in the past year, well above its 34% share of the workforce – the cost-of-living crisis could morph into something much more severe for many Australians.

If I’m going to be critical of Chalmers it’s that he made the RBA’s job more difficult by expanding public expenditure when restraint was what was needed. The last thing you want to do in a demand-driven inflationary crisis is stimulate demand. His government’s actions, along with the states and a slow-moving RBA, have in all likelihood compounded the Morrison government’s mistakes and prolonged the inflation:

“The trouble is that the decisions the government have taken since coming to government have pumped into the economy the equivalent of two interest rate cuts in fiscal stimulus in the current year alone… governments in Australia are making the RBA’s job much harder.”

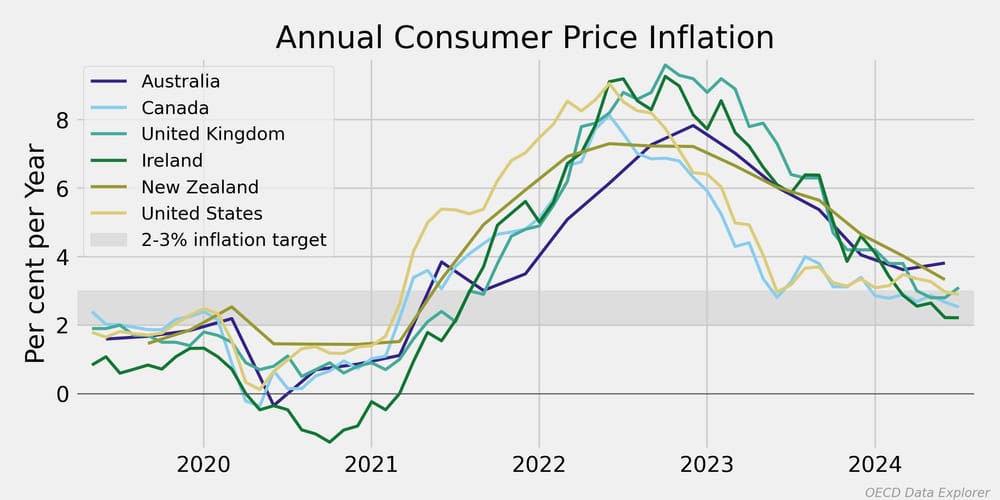

The current per capita recession isn’t something that can be solved with cost-of-living handouts and energy subsidies. It’s the inevitable hangover of prior policy decisions, and the best way to fix that is to get on top of inflation (which the RBA is doing, albeit more slowly than its OECD peers) and improve productivity, which in the long-run is the only sustainable way to increase real wages.

On the slow path

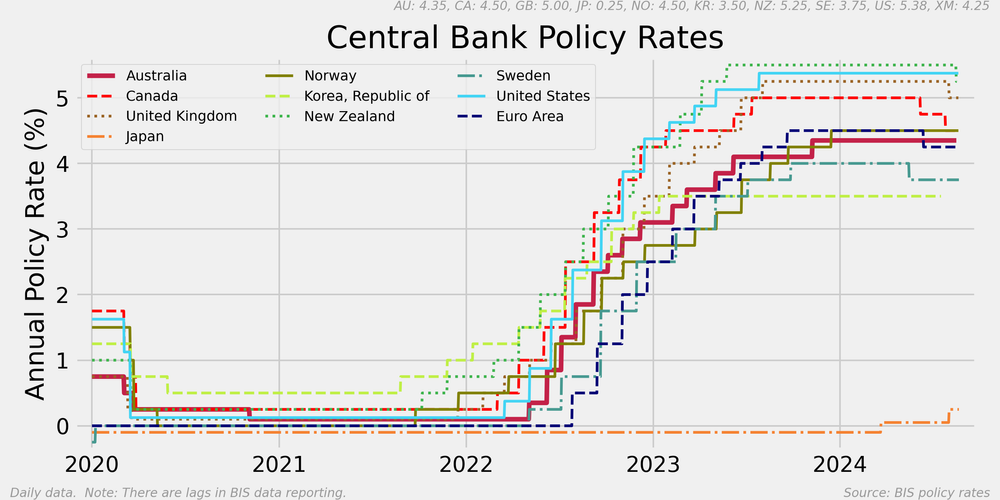

Most advanced economy central banks have already cut rates, or are about to: at its last meeting, Fed chair Jerome Powell said “the time has come for policy to adjust”, suggesting a rate cut in the US later this month.

But the RBA started later and didn’t tighten as much as those countries, leaving us “at least 5 months” behind:

We’re on the slow path to inflation reduction because the RBA chose to favour the employment side of its mandate over price stability. I’m going to oversimplify here, but the economics of the employment/inflation trade-off (known diagrammatically as the Phillips Curve) is generally that because of the money illusion – higher nominal wages mean people don’t realise their real purchasing power has fallen right away, but their expectations eventually catch up – the trade-off only holds in the short-run:

“The more quickly workers’ expectations of price inflation adapt to changes in the actual rate of inflation, the more quickly unemployment will return to the natural rate, and the less successful the government will be in reducing unemployment through monetary and fiscal policies.”

In the long-run, unemployment is a real variable that should be addressed with economic policy. Things like reforming the tax system to make it less punishing on doing productive work, zoning reform so that housing is more affordable and people can more easily move to where the good jobs are, and so on.

The government should probably also stop doing things that will probably harm productivity, like banning a tailings dam through executive action after hundreds of millions of dollars had already been invested and multiple state and federal reviews were cleared.

Indeed, a reason why Australia’s cost-of-living crisis has been particularly hard on so many is because of our tax system – namely, the lack of indexation (leading to bracket creep) – and the dominance of variable rate mortgages. Many other advanced economies haven’t done nearly as badly out of higher rates:

“We estimate that across the European Union, higher interest rates have raised households’ earnings from their savings accounts by 40% more than the increase in their debt repayments—and find similar results for rich countries elsewhere.”

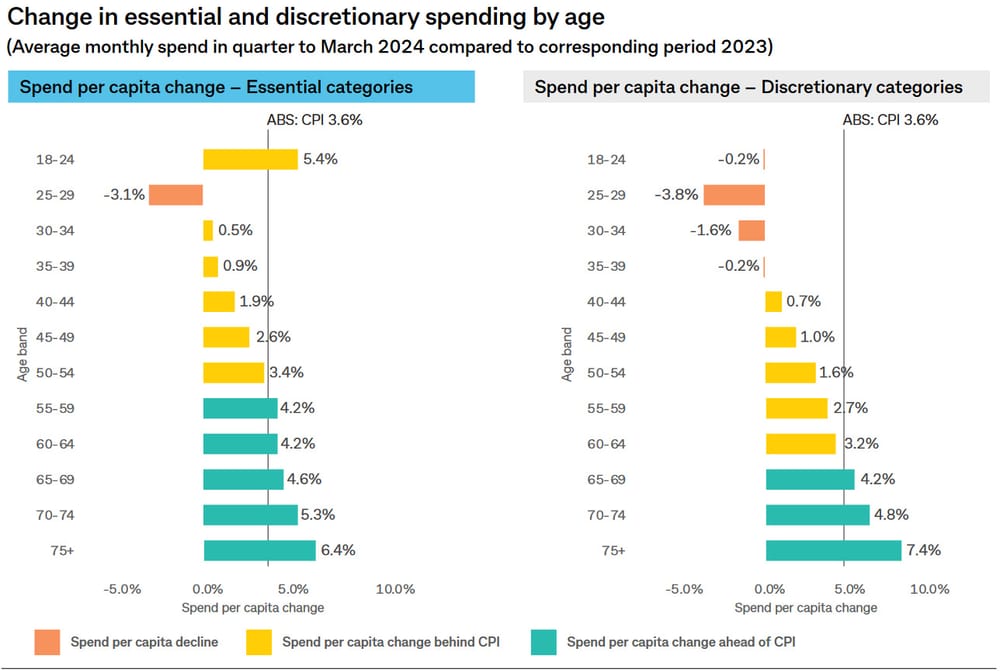

In Australia, the ratio of household deposits to liabilities is around 50%. Given that most of the liabilities are variable rate mortgages, households get hit directly in the hip pocket. It’s especially hard on younger people, as “the households holding most of the savings tend to be wealthier and older, rather than the younger borrowers who are typically most prone to mortgage stress”.

The young also get hit by our tax and transfer system, which “largely ignores the effect of accumulated wealth on a person’s ability to pay for their own needs”. So, younger households are being hit with a triple-whammy of higher mortgage payments, income tax bracket creep, and having to pay for the pensions and healthcare of debt-free retirees living in million-dollar houses.

Where to from here

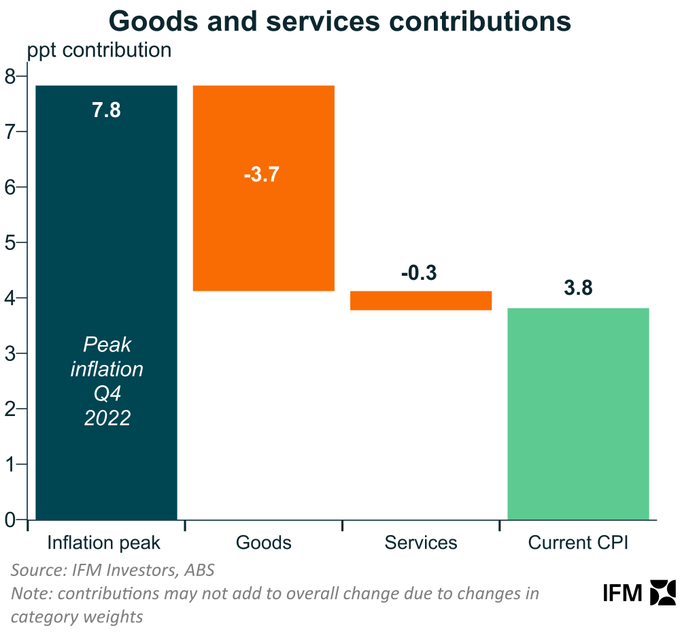

The RBA will be hoping that it can preserve the pandemic’s employment gains long enough for inflation to come down. But with domestically-driven inflation proving relatively sticky – services inflation has barely budged, with most of the price-reduction work being done in tradeable goods (i.e. imported) sectors – and the economy weakening, the long-run may already be here:

However, there is some good news on the horizon. According to data from SQM Research, “asking rents recorded the largest monthly rental falls since the outbreak of Covid”, and construction costs are “showing signs of stabilisation”.

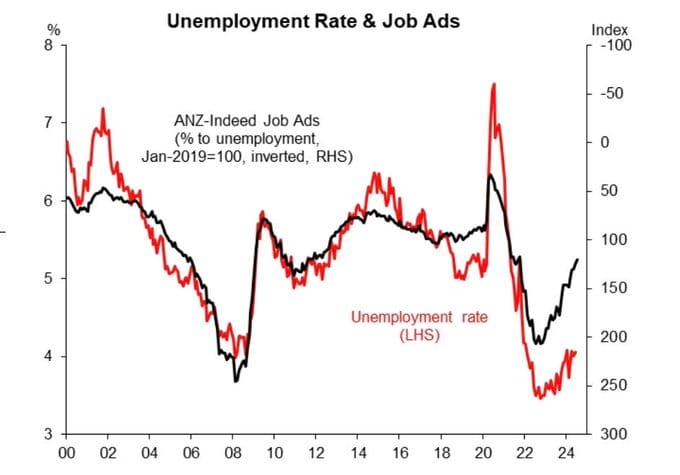

The problem with good news on inflation is it might be indicating bad news for the economy, as if businesses are fighting to remain profitable, they might stop hiring – or even fire people. On that note, job ads fell this week to a three-year low, and they tend to lead unemployment:

A recent survey by Deloitte also found that “the private sector had entered something of a hiring freeze”.

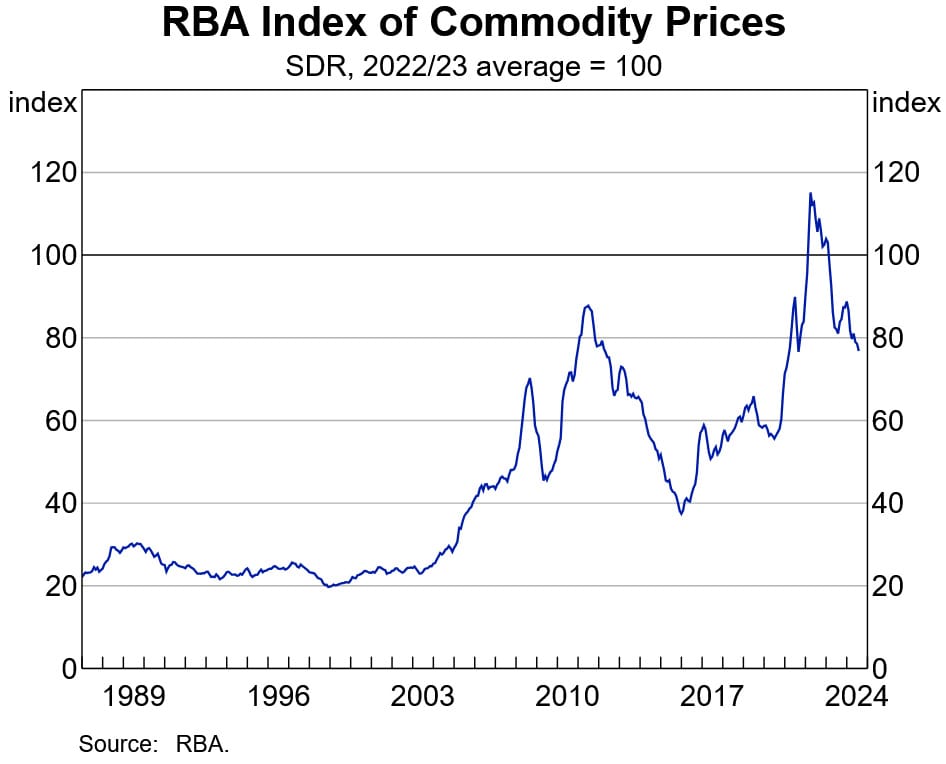

Adding to the weakness is falling commodity prices. Australian budgets live and die by these, especially in states like Western Australia, and they’ve come off a lot in recent months. Still a long way from the depression-level 2015-16 lows, but the trend is what’s worrying:

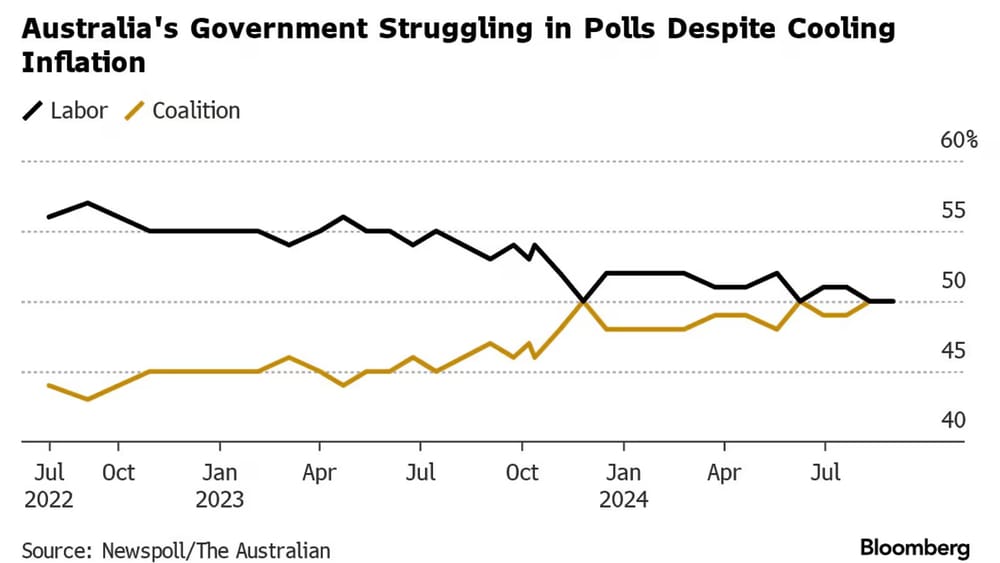

Put it all together and we’re in for a tough several months, which spells trouble for Chalmers and might be why he’s trying to deflect blame onto the RBA. Recent polling by Redbridge “found only 24% of Australians could name a government policy that had improved their lives”, and the latest Newspoll has the two parties neck-and-neck:

The only potential saving grace for Chalmers would be an interest rate cut before the election. But somewhat ironically, the RBA will be able to control inflation without “smashing” the economy only if politicians like Chalmers keep spending under control. He hasn’t done that, so really it’s he who has done the smashing.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!