Wednesday Wisdom (41/24)

It’s a big day for inflation today, with the all-important September quarter consumer price index to be released. In all likelihood it’s going to fall within the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) 2-3% target, but only because of the various “cost of living” support that our governments have pumped into the economy in the last two quarters. By trying to artificially bring inflation down with parlour tricks, we’ve effectively triggered Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure!

So, don’t read too much into the good news that certain politicians will inevitably be crowing from the rooftops later today. The RBA will do its best to ’look through’ any government-induced distortions in the figures, and certainly won’t be silly enough to pull forward a rate cut unless actual inflation, rather than measured inflation, looks like it’s sustainably within target.

Anyway, given that both Friday and Monday were taken up with a double-header on the United States, here’s some Wednesday Wisdom for you, i.e. a bunch of stuff I thought about recently but didn’t think warranted a full post.

The limits to federal housing policy

From what I’ve seen so far, I think Peter Dutton’s approach to housing is better than the Albanese government’s, but it’s a very low bar. I’ve written why in some detail here, but to repeat: there isn’t much a federal government can do to fix housing, so while the Albanese government’s policies cost a lot of money, their impact on affordability is likely to be minimal.

For example, proposals like Help to Buy and Build to Rent are gimmicks that have been proven not to work in other countries. The Housing Australia Future Fund looks like it will mostly just crowd out market-rate housing that would have been built anyway, at the taxpayer’s expense. And the Housing Accord – while initially promising because it intended to ask states to “expedite zoning, planning and land release” – has leaned so heavily on its “social and affordable” mandate that it will almost certainly fall well short of its targets.

As for Dutton’s plan, the details are still light and it’s certainly not all good. Here’s the gist:

- $5 billion to fund critical housing infrastructure — like sewerage, water and power.

- A 10-year pause on changes to the National Construction Code.

- Super for housing, allowing first homebuyers to withdraw up to 40% of their super.

- Cut the permanent migration program by 25% for two years.

- Ban foreign investors and temporary residents from buying existing homes for two years.

I’ve covered the last three points here. They’re all fairly bad ideas that will do virtually nothing to improve housing affordability. In the case of super for housing, it will only change the distribution of who is able to buy their first home (e.g. those with larger super balances, such as men, will be advantaged over women who have had a career break for childbirth), but won’t make them any more affordable. There might be an equity argument for it – i.e. should people have more freedom over where their forced retirement savings are invested – but there’s not much of an economic one.

But the first two points above – which are also the most recent – have some merit.

The first point on housing infrastructure funding at least gets the incentives right: developers and local governments stand to gain only if they actually build. The housing bottleneck isn’t for want of capital or developers willing to build, but the permission to do so – and sometimes that includes waiting around for government to approve or build the necessary supportive infrastructure.

On the second point, I think pausing the National Construction Code is a good idea. Dutton claims it adds $60,000 to the cost of a build, which I can’t verify; opponents such as the Australian Glass & Window Association (AGWA), which stands to gain from future additions to the Code, “says the average cost to upgrade new homes in major Australian cities to 7-star energy ratings is closer to $5,000”.

They appear to be talking about different things: Dutton the total cost of the Code, with the AGWA referring only to changing from a 6-star to 7-star energy rating. Either way, there’s no debate that the Code adds to the up-front cost to build a new house.

So, why do I support Dutton’s pause? First, let’s look at one of the most vocal critics of the plan, ACT senator David Pocock, who claimed the freeze would be be “seriously regressive”.

I’m not sure how Pocock can possibly make such a claim, which appears to demonstrate a severe lack of economic understanding. Specifically, his inability to think on the margin: the cost of making the Code require 7-star ratings isn’t just $5,000; it’s $5,000 plus the cost of all the other regulations that came before it. Given that wealthy households are the ones most able to afford changes to the Code that raise construction costs, it’s Pocock who is being regressive here.

Think of it another way. Just because you ban economy class doesn’t mean everyone can now suddenly fly in business class. What would happen is many of the people who were previously flying economy would now no longer fly at all.

In the context of housing, adding another $5,000 layer of regulation onto new housing may not seem like much, but it all adds up and makes housing less affordable. Most people will live in more energy efficient homes, but at the margin, some people will now miss out on housing all together.

But households will save on their energy bills in the long run because of the added efficiency, right? Not necessarily: a more energy-efficient home also reduces the cost of heating or cooling it, which will increase the amount people heat and cool their homes. Economists call that the rebound effect (or Jevons Paradox), and if demand is sufficiently elastic, people could even end up using more energy when their houses are more efficient.

It’s just one of many important considerations policymakers should appropriately weigh before imposing regulations that, by raising upfront costs, will certainly deprive some people of housing. And for me, anything that makes new housing construction even more expensive during a housing crisis just doesn’t seem like it would be a very good thing to do, which is why I support Dutton’s plan to pause changes to the Code.

Anyway, the good news is that not all is lost for the Albanese government. Treasurer Chalmers – armed with the Treasury modelling he requested – recently said that:

“I think it is primarily a supply challenge… one of the reasons why we’re not going down the path of changing the negative gearing arrangements, abolishing negative gearing or abolishing the capital gains tax discount, is because we haven’t been convinced that that would have positive consequences for supply.”

The government’s new housing minister, Clare O’Neil, also appears to understand the real problem, and “has backed business groups and economists wanting states to dump stamp duty, saying ‘it’s a really good idea’.”

However:

“We can certainly ask the states to do it but I’m a Commonwealth minister and as you know, it’s not my power to tell states what to do.”

And therein lies the problem. No matter who wins next year’s election, most of the nation’s housing problems are due to state and local government decisions. There is only so much a federal government can do.

The magic of quantitative easing

Otherwise known as how to lose a truck load of cash.

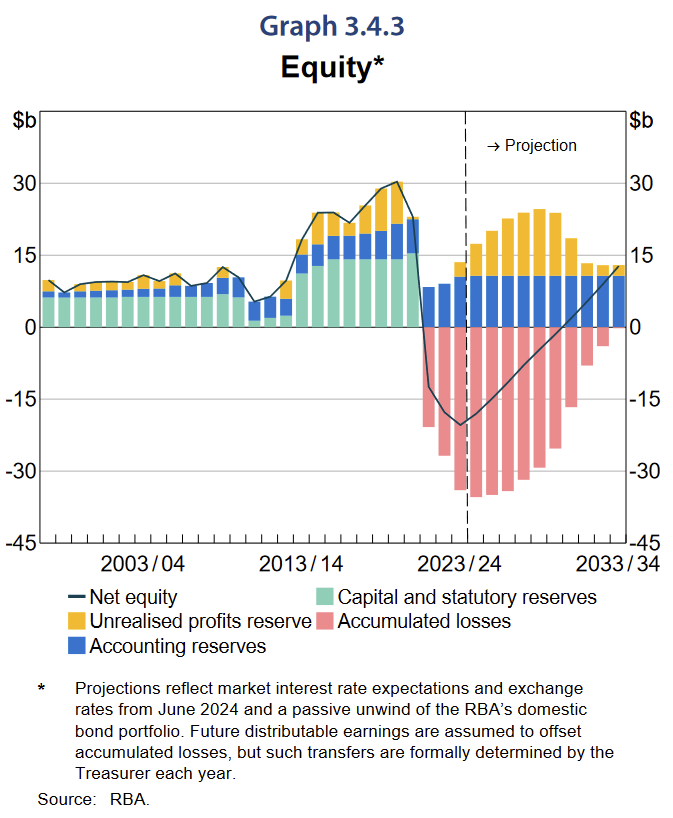

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) released its 2023-24 Annual Report last week, showing that its accumulated losses from its dabble in quantitative easing (buying bonds with ‘printed’ money) have now passed $30 billion. With more than $20 billion of negative equity still on the books and no sign of rate relief coming any time soon, those losses will continue to grow for a “further decade or so”, and it’s unlikely to be able to pay the government a dividend until that time.

I first wrote about why this is happening back in February:

“When inflation showed up and the RBA eventually started tightening monetary conditions, the low-yielding bonds it bought at record-high prices were worth much less. To credibly tighten monetary policy, the RBA also had to start paying higher rates of interest on ES [exchange settlement] balances than it receives from those bonds.

…

If inflation proves to be persistent and the RBA has to hold rates at present levels, or raises them even more, then the losses it realises on ES balances will continue to grow until the final bond rolls off the RBA’s balance sheet in 2033. The RBA’s own estimates suggest it could lose between $35 to $58 billion on ES balances by 2033. Add that to the guaranteed $19 billion loss on its bonds and the total fiscal cost will be above $50 billion.”

Worst of all, it was all done by unelected bureaucrats without a single internal cost benefit analysis, despite having had ample time to conduct one (the RBA acted months after several other central banks had started their own bond buying programs, with no measurable success).

A smaller Canada

Two years after Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, boldly announced his big Canada policy “because immigration is critical to growing our economy and helping businesses find the workers they need”, he’s now closing the door:

According to Canadian economist Mike Moffatt, the change is so drastic that Canada will actually start to shrink if the plan is executed in its current form:

“Federal government has released their new immigration plan… it’s even more bold than I had anticipated. I thought it would show population growth of 50,000 a year. Instead, it’s showing population DECLINE of 80,000 a year in 2025 and 2026.”

Instead of implementing the policies that would free up supply by allowing people to build the infrastructure and housing needed to accommodate more migrants, Trudeau has decided to take a leaf out of the book of Anakin Skywalker, aka Darth Vader:

I expect the backlash against immigration to keep growing in Australia because they’re easy targets for struggling politicians to scapegoat. When in doubt, blame the foreigners, right?

The global demographic decline

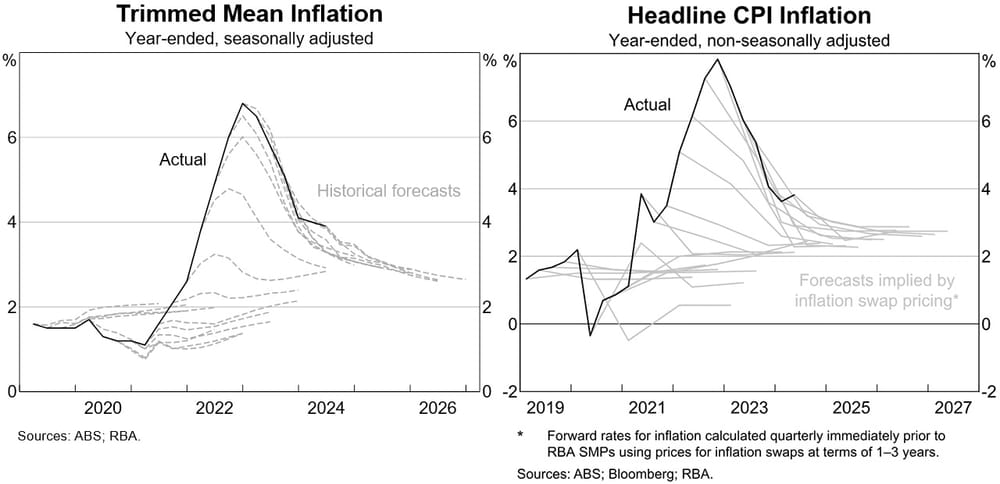

Back in August the RBA’s Andrew Hauser warned us to “beware false prophets”, using examples of its own forecasting and market expectations as reasons “to avoid placing too much reliance on point forecasts in the first place”:

Well, it turns out that the UN’s population projections are just as unreliable:

“[O]ne after another, the projections keep missing, repeatedly underestimating the pace and duration of falls in birth rates. To give one example, just five years ago the UN estimated that there would be around 350,000 births in South Korea in 2023. There were actually 230,000, more than a third fewer.

South Korea is almost too lazy an example in demographic discourse, but similar misses are increasingly common. Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania and a prolific researcher on the intersection of economics and demography, highlights Latin America, where the official birth tallies in country after country are falling far short of forecasts.

Last year in Colombia there were 510,000 births, a 22 per cent decline over five years, and around 30 per cent lower than even the UN’s nowcast for that same year. From high-income Chile to emerging Guatemala it’s a similar story, and this issue is far from specific to the UN data, whose projections are generally closer than those of the IHME and IIASA.”

If the latest estimates are to be believed, global population could peak in 2054, a full “30 years earlier than in the headline forecast”.

But any forecast that far out is worth less than the pixels it’s displayed on: for all we know, the demographic decline will self-reverse, either due to changing norms or through innovation that allows fertility to remain high later in life.

No one can know! It’s hard enough predicting the weather tomorrow, let alone global demographic dynamics many years into the future.

There’s a lot of AI snake oil being peddled

Should we be worried about artificial intelligence (AI)? According to Princeton computer scientists Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, there’s a lot of snake oil being peddled – so much so that they wrote a book called AI Snake Oil.

AI blogger Timothy Lee recently reviewed it, taking away several insights:

“Narayanan and Kapoor stake out a sensible position between these extremes. They write that generative AI has many ‘beneficial applications’, adding that ‘we are excited about them and about the potential of generative AI in general’. But they don’t believe LLMs will become so powerful that they’re able to take over the world.”

I agree. I’m both amazed by AI and also deeply unsatisfied, because I’m well aware of the limits of LLMs (large language models) and that it will never come close to achieving artificial general intelligence.

Which brings Lee to regulation:

“[The authors are] sceptical that future AI systems will have either the capacity or the motivation to gain power in the physical world. They urge policymakers to focus on specific threats, such as cyberattacks or the creation of synthetic viruses. Often the best way to do this is by beefing up security in the physical world—for example by regulating labs that synthesise viruses or requiring that power plants be ‘air gapped’ from the Internet—rather than trying to limit the capabilities of AI models.”

That’s more or less my view, too. As I wrote back in June:

“We already have a litany of laws and regulations that are well equipped to handle many possible unintended consequences of AI… the best course of action might just be to let this new industry play out and deal with any consequences as and when they arise.”

I don’t put much weight on the arguments of so-called ‘AI doomers’, who appear to misunderstand the coordination problem and, as Narayanan and Kapoor note, “the complexity of social situations”.

That’s not to say AI can’t cause harm. For example, the ‘air gapped’ policy above makes a lot of sense – human hackers already target things like virus labs and power plants, and with AI they will get even better at it.

Firms using AI should also be careful to have the right policies in place. For example, if you’re getting AI to transcribe medical records, you probably don’t want to give it the originals without storing a backup first!

Fun Fact

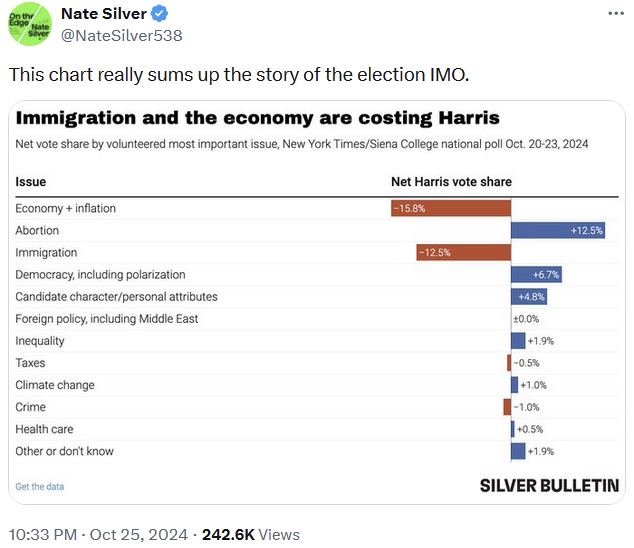

These issues, perhaps with the exception of abortion, will also define the next federal election in Australia:

As the incumbent, the Albanese government will cop heat for the economy, inflation and immigration, none of which look likely to ease much before May 2025.

Have a great day.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!