We're number two!

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) released its World Economic Outlook (WEO) last week, a twice-a-year document containing updates to its forecasts and commentary on various trends in the global economy. This year it covered changes in mortgage and housing markets (which I already wrote about here); the world’s medium-term prospects, including the “persistent structural frictions preventing capital and labour from moving to productive firms”; and the dimmer prospects for growth in China. It’s always worth a read if you’re into those kinds of things.

Alongside the WEO, the IMF also publishes a fiscal outlook. That’s what I want to look at today, because it led to plenty of back-patting here in Australia, such as this tweet post from Finance Minister Katy Gallagher containing not one, but TWO party face emojis!

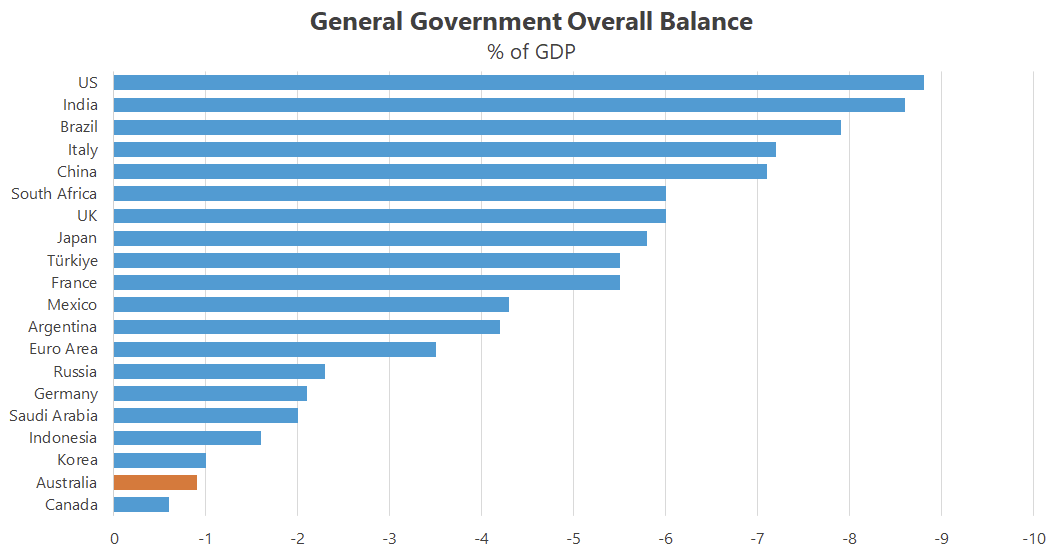

The celebrations were because we ranked second on the IMF’s “General government overall balance” metric in 2023, which is an indicator of relative fiscal performance. Treasurer Chalmers deemed the result worthy of an official media release, stating it was “a remarkable improvement”, and “a testament to the Albanese Government’s responsible approach to budget management”.

Cross-country comparisons are tricky

That’s one interpretation. While it’s true that Australia’s Budget balance – note the IMF includes states and territories in these numbers – and G20 ranking has improved considerably since 2021, there were a few other things going on back then.

For one, it was a year heavily distorted by the pandemic. Governments everywhere were spending big (raising the numerator), and many economies were still severely restricted (reducing the denominator). But not everyone went through the pandemic together, or responded with the same vigour, with spending and movement restrictions occurring at different points throughout 2020-22. Australia was one of the biggest spenders and had some of the most severe lockdowns in 2021, so it was always going to look bad against G20 countries on this metric.

Basically, 2020-22 are really not good years on which to be doing cross-country comparisons. Even sensible Singapore blew its Budget during the pandemic, ranking 19th out of the 28 advanced economies covered by the IMF. In 2023 it was back to #2, despite no change in government.

Moreover, if you add the other advanced economies into the mix then Australia suddenly doesn’t look all that good: in 2023, Norway, Singapore, Cyprus, Denmark, Andorra, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, Croatia, Sweden, and Lithuania also all managed their budgets better than Australia.

But that’s just nitpicking; I’m not trying to pretend that the last Coalition government were good budget managers. To the contrary, I think that ScoMo/Frydenberg were a couple of the worst economic managers we’ve seen for a long time. But what I do take issue with is Chalmers and Gallagher claiming the result is entirely due to their “responsible approach to budget management”, when it was mostly due to dumb luck.

The lucky country strikes again

It’s no coincidence that Australia and Canada topped the G20 for budget management in calendar year 2023. Both are major commodity exporters that collected plenty of additional royalty and company tax after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused oil and gas prices to go haywire. Then there was the excessive global aggregate demand stimulus during and following the pandemic, which caused just about all commodity prices to shoot up. Governments in both countries were also huge beneficiaries of the ensuing inflation, in that the additional nominal spending caused revenues to spike without an immediate increase in expenditures thanks to the considerable lags involved on that side of the ledger, and unlike in 2021, direct pandemic-related support had been withdrawn.

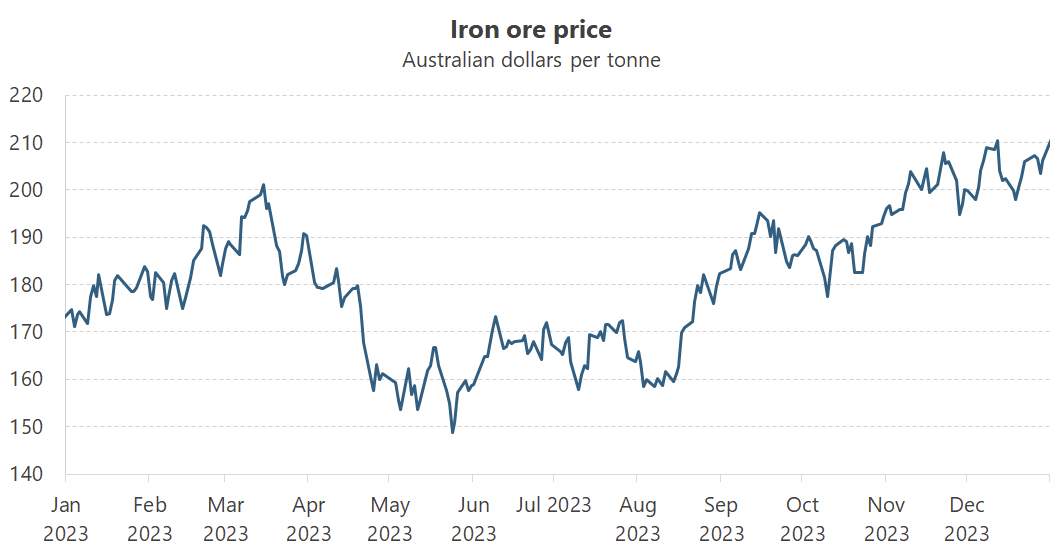

Iron ore averaged $180/tonne in 2023.

As a result of the surge in nominal spending and higher commodity prices, government revenues soared. Bracket creep has ripped throughout both economies, with items such as GST thresholds and various tax deductions not indexed to inflation. While Canada indexes its federal income tax, its provinces only do it on a somewhat ad-hoc basis (if at all). As far as I’m aware, Australia doesn’t index any of its taxes, and the much-hyped stage 3 tax cuts still don’t even kick in for a few months. All of those automatic revenue-raising mechanisms combined to flatter both provincial (state in Australia) and federal government balance sheets:

“In the case of Alberta, revenues from non-renewable resources jumped nearly 500% from a budget estimate of $2.9 billion… Elsewhere in Canada, strong recoveries in business activity and labour markets led to much higher than expected corporate income tax and personal income tax revenues. Rising wages and salaries also likely contributed to some degree of tax bracket creep. This is particularly the case in Ontario, Alberta, and B.C., where year-over-year growth in wages and salaries were highest in the country. As solid consumer spending and rising inflation fuelled sales tax revenues, most provinces saw revenue growth outpace increases in expenditures by a factor of two to one.”

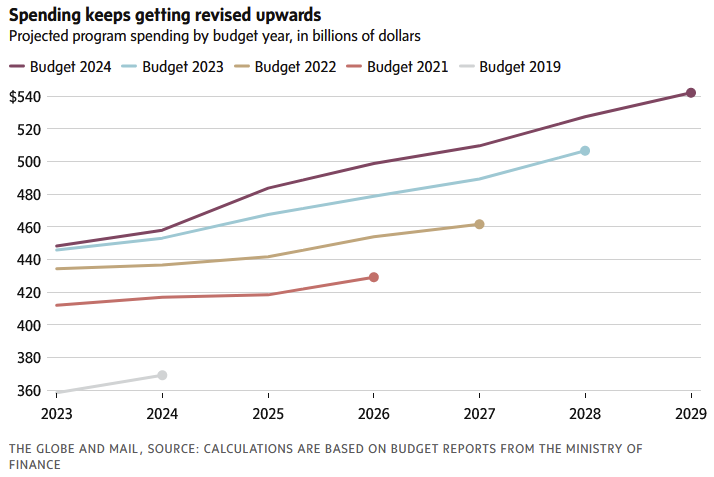

Meanwhile, expenditures lagged, in large part because a large percentage of government costs – especially at the state (provincial) and territory level – are public employee salaries, which did not rise to the same extent. Additionally, many spending measures announced during and after the pandemic will inevitably experience cost blowouts as inflation is eventually priced into their contracts, but those were not fully expected or reflected in 2023 Budgets. Looking at Canada’s federal government, its estimated expenses have a bad habit of being revised upwards after the fact:

According to Canada’s TD Bank, Canada’s federal government is spending as though the inflationary revenue windfall will be permanent:

“Importantly, the government isn’t ‘banking’ this fiscal improvement, as new spending more than offsets the improvement in revenues… the fiscal plan is still reliant on a steadily expanding economy, even if modest. Any major economic potholes would leave Canada vulnerable to missing the fiscal anchors.”

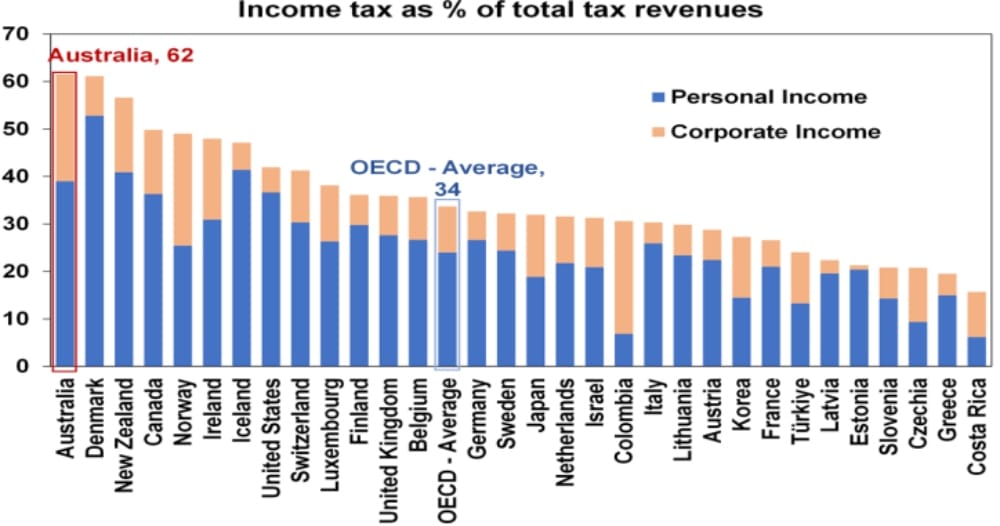

The same is true in Australia, with our central government extremely reliant on income and corporate taxes that have benefited from inflation, and our states dependent on pro-cyclical stamp duties and payroll taxes (in NSW those two items make up 60% of total taxation revenue) or commodity royalties.

Less, not more, resilient

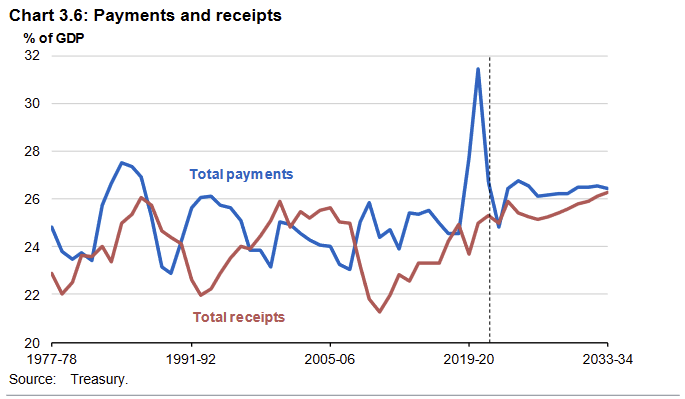

If economic growth slows then Australia’s governments will be just as vulnerable to a fiscal shock as Canada’s. In its last Budget, Australia’s federal government expected its spending to continue growing faster than revenue despite those revenue windfalls, with the underlying cash balance to remain in deficit for the foreseeable future.

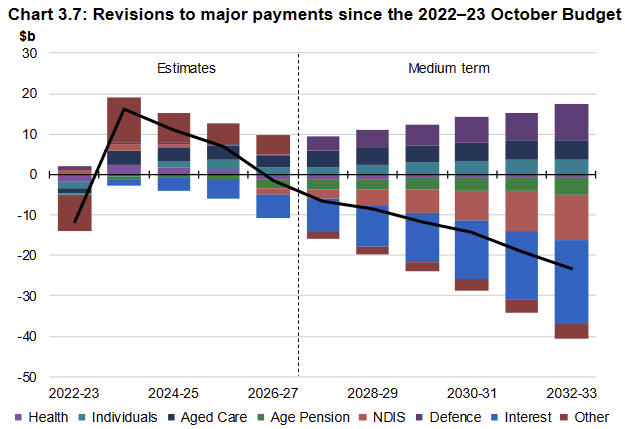

Perhaps more worryingly, the savings it expects to achieve are coming from two main areas: interest payments and the ever-expanding National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

While the latter is a policy decision and it remains to be seen whether the government will be able to fulfil its ambitious plans to rein in the NDIS, interest payments may not ease as much as Treasury is expecting. That’s because of the elephant in the room, the US, and the fact Australia is now engaging in a decent amount of policy mimicry by following the US down the slippery protectionist slope of industrial policy. According to the IMF:

“In 2023, the United States experienced remarkably large fiscal slippages, with the general government fiscal deficit rising to 8.8 percent of GDP from 4.1 percent of GDP in 2022, despite strong growth… The overall fiscal deficit is projected to persist at more than 6 percent of GDP over the medium term.

…

In sum, the previous analysis points to risks from loose fiscal policy in the United States along several dimensions. Loose US fiscal policy could make the last mile of disinflation harder to achieve while exacerbating the debt burden. Further, global interest rate spillovers could contribute to tighter financial conditions, increasing risks elsewhere.”

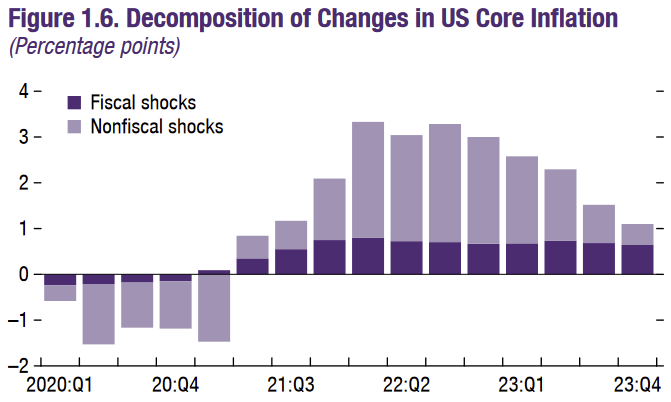

People have been talking up the US economy in recent months – it’s leading most advanced economies on many macro growth metrics – but a large part of its success is due to a huge, ongoing federal fiscal impulse. As the IMF notes, that’s not sustainable and is building risks, both in the US economy and overseas. It provided the following chart showing that a considerable amount of the ‘sticky’ core inflation in the US is being caused by the government’s deficit-financed fiscal spending.

It also warned that when long term interest rates in the US rise by 100 basis points (say, due to persistent inflation and declining confidence in the government’s ability to pay its debts), its dominance in global finance means it creates significant spillover effects, raising long-term nominal rates in other advanced countries by around 90 basis points “with a persistent impact over many months”.

The combination of US profligacy, and Australia’s recent penchant for policy mimicry and continued spending growth at all levels of government, means we’re very unlikely to see rates cut this year. In its report, the IMF said the right approach to rebuilding fiscal buffers “is to start now, gradually, and credibly. Once inflation is under control, credible multiyear consolidations will help pave the way for further monetary policy easing”.

It also cautioned against industrial policy, warning that it’s harmful for medium-term growth, reduces efficiency, raises geoeconomic fragmentation, and the “net effect could well be to make the global economy less, not more, resilient”.

Best of a bad bunch

In Australia, that means instead of throwing cash at people in the face of an inflationary cost of living crisis that will only make it worse, we should work towards productivity-enhancing tax reform. Instead of ensuring Australia’s “future” with billions in tax credits, subsidies and state-directed investment into manufacturing things for which we have no comparative advantage, we should stick with what we know works for a small, open economy such as Australia’s. That means eliminating trade barriers, easing red and green tape, and getting serious about fixing the constraints that have gummed up housing supply. It also means spending less and spending smarter, so that when the next crisis inevitably rolls around we have the fiscal capacity to actually help people.

The IMF, optimistically, said that there’s “still time to reverse course” away from industrial policy and all of its harmful, long-run effects. But do I think this federal government, or any of our state governments, will act on its recommendations? Sadly, no. In the next year and a half, we will have elections in WA, the NT, QLD, the ACT, TAS, and of course federally. Politicians will happily tweet about IMF reports when it suits them, but politics will trump economics in 2024-25, and that means handouts and quick fixes will be prioritised over reform and fiscal restraint.

We might have been number two in the G20 in 2023, but being the best of a bad bunch is not something about which we should be boasting.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!