What Australia's per capita recession really means

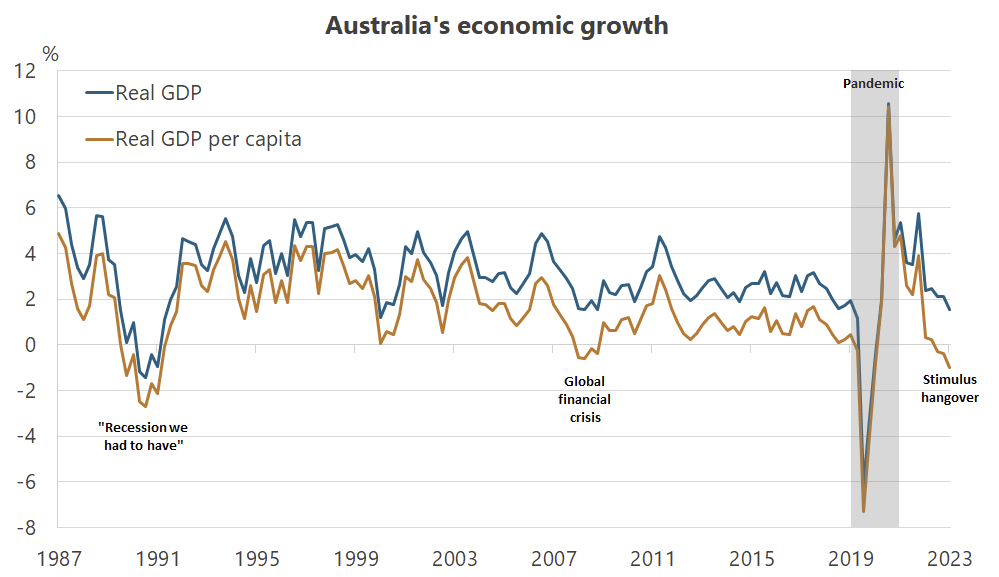

Australia’s national accounts were released last week and confirmed that our per capita recession – defined as two consecutive quarterly contractions – didn’t just continue into the December quarter, but deepened: on a per person basis, our economy is now a full 1% smaller than where it was a year ago.

Excluding the pandemic, it’s Australia’s first per capita recession since 2009, and only our second since the depths of the early-1990s “recession we had to have”.

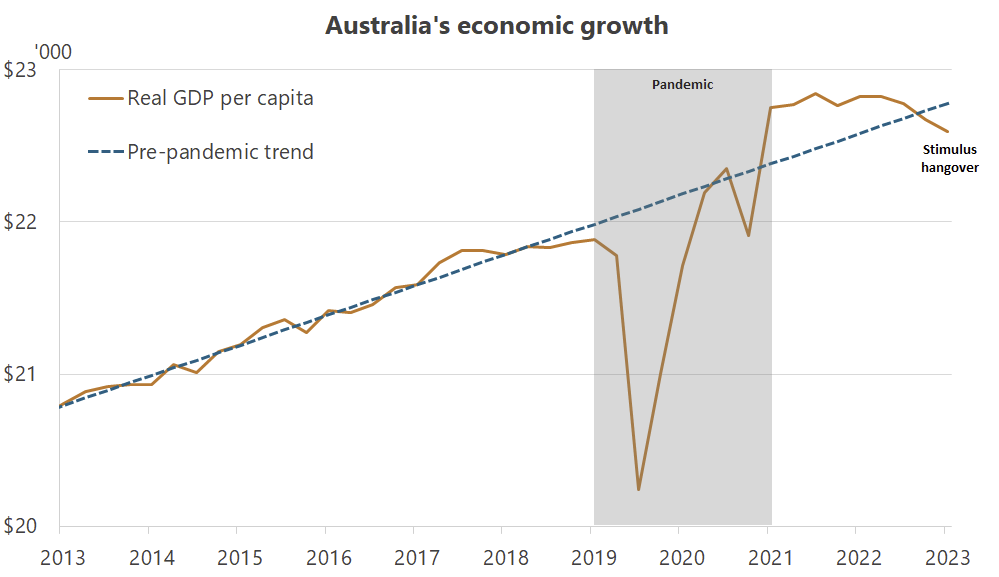

If the current slowdown in real GDP growth continues its current trend, we could soon have our first technical recession since then, too, although we’re kind of already there, anyway: in level terms, real GDP is now well below the pre-pandemic trend.

The fact is that despite above-trend growth for a couple of years, we lost a considerable amount of wealth during the pandemic. So, what should we make of the rather sombre news, and what can be done about it?

Diving into the aggregates

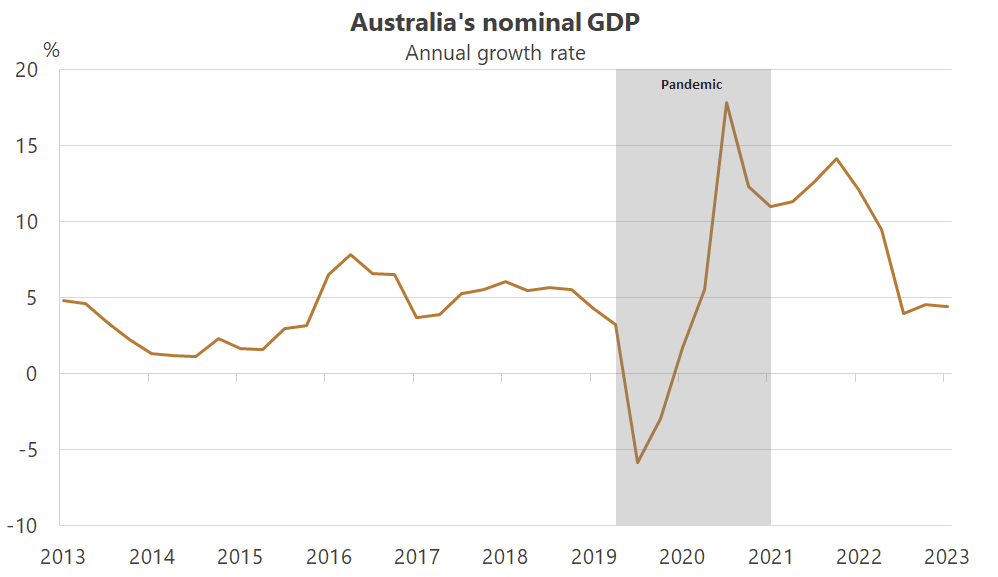

The first thing I’ll note is that an economic slowdown was probably inevitable after the stimulus-fuelled largesse of 2021-23, a period when nominal GDP (NGDP) – a broader indicator of aggregate demand pressures than the consumer price index – was consistently growing in the double-digits.

While NGDP is not as reliable an indicator in Australia compared to, say, the much more diverse US economy – mostly because of how influenced we are by changes in global commodity prices – it can still be important, as it is in this case. For example, since 1990, other than a single quarter in 2009, Australia’s NGDP had never increased more than 10% annually. Yet across calendar 2021-22, it grew above 10% for seven consecutive quarters.

Needless to say, NGDP running at that rate is an indicator of excessively easy monetary policy, which we know is exactly what happened during and following the pandemic. The good news is that it has now been back at around 4.5% for three consecutive quarters, suggesting that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) may soon have inflation under control, at least from a monetary perspective.

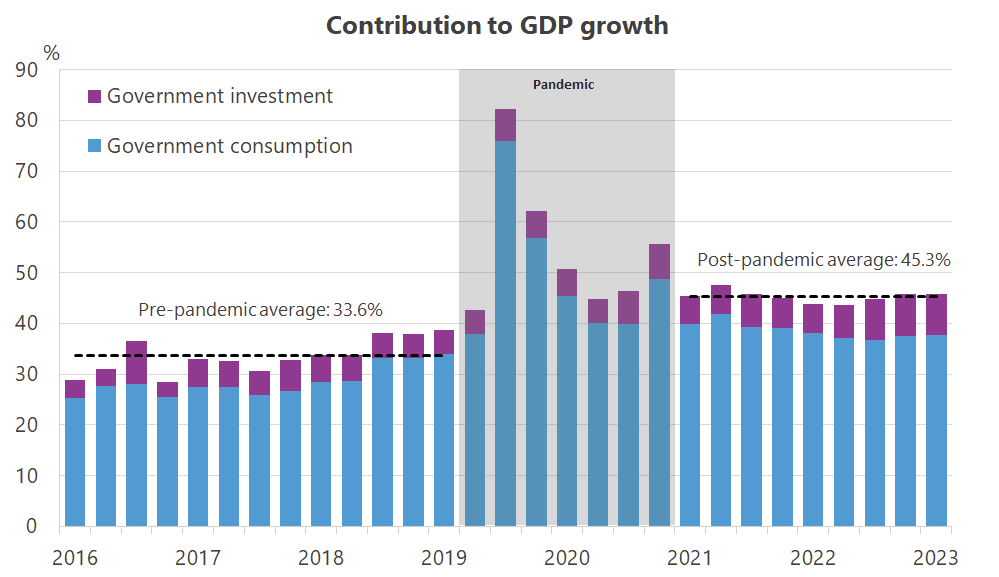

The bad news is that not only has the monetary punch bowl been removed, but a lot of the growth we experienced over the past few years was driven by a seemingly permanent level change in the contribution of government consumption to Australia’s economy.

The private sector was responsible for only a touch over half of real economic growth since 2021, compared to an average of around 70% prior to the pandemic, with the public sector – specifically, debt-financed state and federal government consumption – doing the bulk of the heavy lifting since then.

It’s too early to say if this is a permanent shift in the structure of the Australian economy: a decent chunk of the increase in consumption has been for “government benefits for households”, which are not likely to be sustained beyond the next election. However, the ABS also reported “higher employee expenses across commonwealth departments”, which could prove far stickier.

Generally speaking, a larger role for less productive government consumption crowds out the private sector (the government can only consume by taxing the private sector or through borrowing, the latter of which will need to be paid with future taxes or inflation), and probably contributed to the excess aggregate demand that led to inflation and cost of living crisis. If we want to help improve productivity and reduce inflation, we’re probably going to need to see those blue lines come back down.

The prospect of stagflation is still very much alive

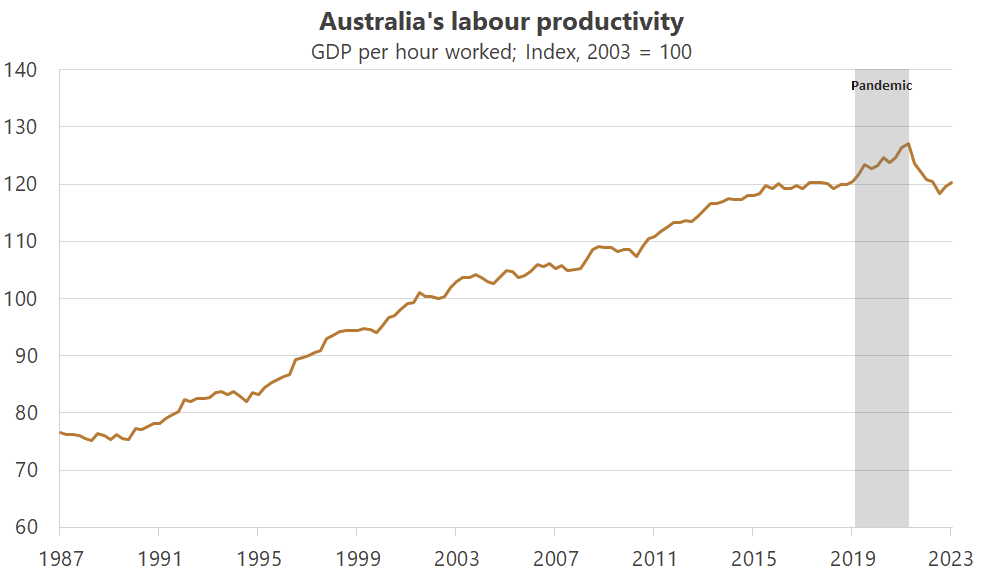

Speaking of productivity (measured here as GDP per hour worked), in the long run it is the key driver of real wages growth, even if the two can temporarily “decouple”. Fortunately, labour productivity increased for the second straight quarter in December, bringing it back to around where it was prior to the pandemic.

According to the Productivity Commission, the post-pandemic decline in labour productivity was due to people having to work more hours to support themselves amidst the cost of living crisis, and these “new workers did not match the (measured) productivity of those already in the workforce, bringing overall productivity down”.

“The decrease in labour productivity was a result of large increases in hours worked for the whole economy and market sector (both 6.9%). This increase in hours worked is unprecedented – the next highest growth rate on record was 4.3% for the whole economy (in 1988-89), and 3.8% for the market sector (in 1999-2000). The growth in hours worked outpaced growth in output for the whole economy (3%) and the market sector (3.8%).”

Essentially, the productivity growth during the pandemic was illusory; we’re simply back to where we were, which is exactly what we should have expected given the lack of reform during that period (productivity doesn’t just magically appear because we want it too).

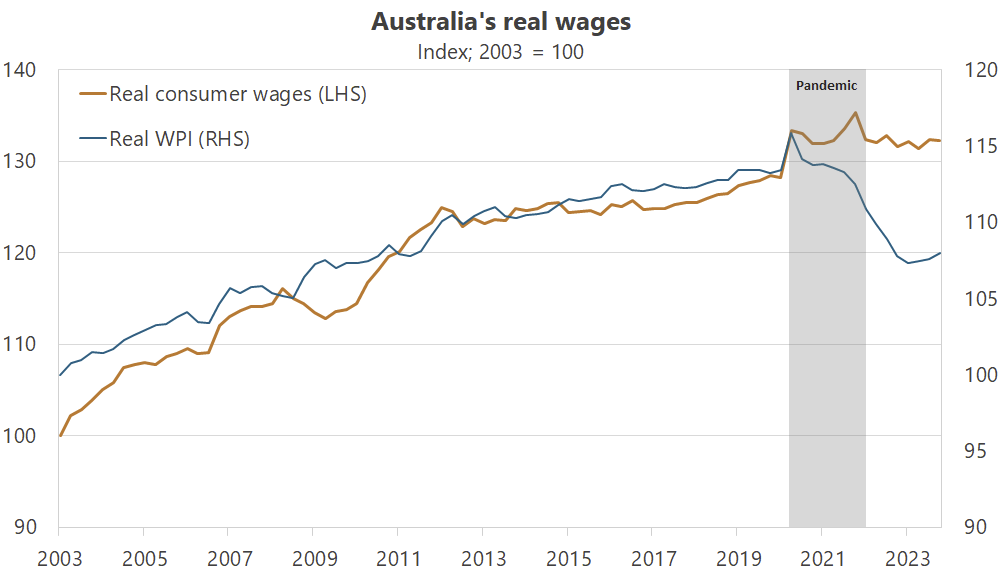

The lack of productivity growth has implications for real wages, given the before-mentioned links between the two. The most common way to measure real wages, and what you will have seen in the media and from politicians bemoaning their decline, is by deflating the wage price index (WPI) for inflation. But the WPI has considerable lags, ignores bonuses, and may not fully capture pay increases people might get from switching jobs.

In turbulent times such as these, I prefer a broader measure called the real consumer wage, which looks at how well aggregate wages keep pace with price changes in the things people actually buy. It’s calculated using total non-farm compensation per employee, deflated by household final consumption, so it more closely represents real purchasing power amongst the nation’s workers than does the WPI.

While real consumer wages have been flat, they’re still above where they were at the start of the pandemic. In other words, the situation for workers isn’t quite as bad as the media and politicians are making it out to be. Households are getting by, whether it’s by changing employers, working more hours, or even picking up a second or third job.

Don’t get me wrong; that’s not a sign of a healthy economy. Quite the contrary, in fact – we’re having to work more hours to offset declining productivity and living standards. Additionally, many of the jobs created in our historically strong labour market were in government and related sectors, such as health care, social assistance, education and training, which accounted for two-thirds of jobs growth in 2023. Those are of course important jobs, but they’re not all that productive or market-orientated, suggesting that the private sector is struggling.

Which brings me to my final point on wages: the risk for Australia is now stagflation (low growth and high inflation). NGDP growth at around 4.5%, combined with the lagged effect of nominal wage increases locked-in over multiple years (e.g., the NSW construction union is pushing for an unprecedented 26% increase over three years), could see measured inflation become ‘sticky’ at the same time as economic growth slows.

In such an environment, the RBA will struggle to justify rate cuts for fear of entrenching inflationary expectations even further, potentially condemning us to years of insipid growth in the absence of impactful economic reform.

No white knight

If you were hoping for China to ride to Australia’s rescue with another big steel-hungry stimulus, you’re in for a disappointment. While the recent budget looks to be “slightly more expansionary than last year’s”, China’s problem will again be whether its government can deliver what’s planned. That’s because the majority of the fiscal spending is expected to be done at the local government level, but because of all the problems with previous “investments”, that may prove difficult:

“A problem that hampered the spending was Beijing’s requirement that these local special bonds be used only in infrastructure and public welfare–related projects that can generate sufficient returns to cover interest payments of the bond issues. But local governments, especially in less developed inland provinces, cannot find enough projects that can meet the central government’s requirements, partly because of their overinvestment in infrastructure in previous decades.”

The FT reported that in just one local government area, south-western Yunnan, “1,153 government-funded infrastructure projects such as highways and theme parks have been suspended and new construction halted to limit expenditures and focus on debt resolution”.

Needless to say, a steel and construction-led boom – such as the ones Australia benefited from after 2009 and again in 2020 – is unlikely to happen, especially as the central government has publicly vowed to “firmly prevent any increase in hidden government debt and steadily address existing hidden debts”.

Compounding China’s growth woes, Xi Jinping has gradually increased his control over the economy, suffocating the private sector:

“To reinvigorate its economy China needs to harness the private sector. Private investments are half of the national total but fell by 0.4% in 2023, largely because of the property slump. But given its unstable regulation and official paranoia, the government has no good way to repair confidence among gloomy entrepreneurs. Multinational investment is at a 30-year low. Investors are so disillusioned that the valuation discount on Chinese shares compared with American ones has reached 54%.”

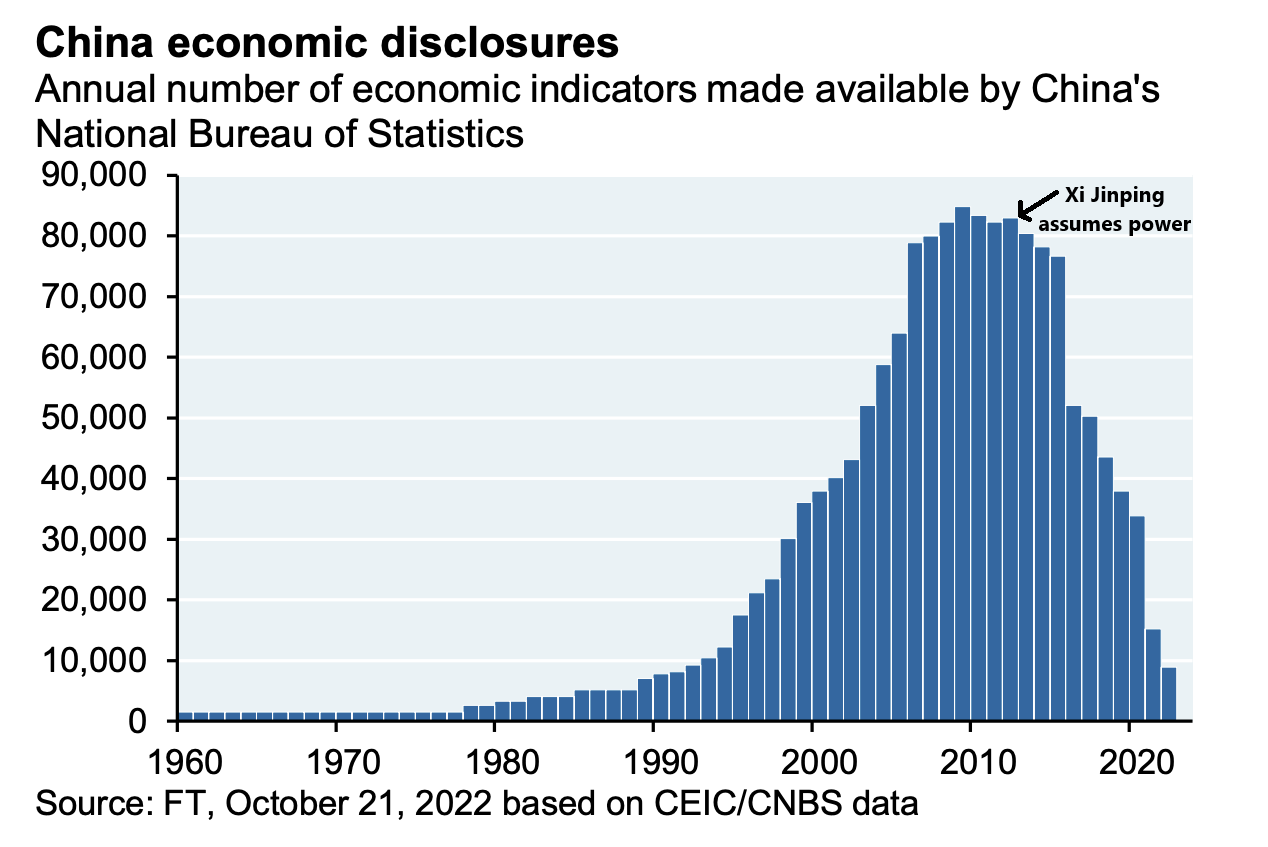

And if that wasn’t enough, investor confidence is being rattled by the constant reduction in published economic data under Xi’s watch:

While I would never put much weight on any data published by China’s government, the trend is certainly worrisome, especially when combined with “the disappearance of prominent entrepreneurs, a new espionage law making it hard to do business, the dramatic shift of capital and loans away from the private sector to state-owned enterprises, just to name a few”.

Where to from here

If China isn’t going to bail us out, then we’re going to have to do it ourselves. Treasurer Chalmers fancies himself as a bit of a reformer, and he finally did something on that front this week by removing 500 so-called ’nuisance’ tariffs:

It was a great move, and one can only wonder why more than a decade of ‘pro-business’ Liberal leadership never got around to doing it; none of the goods tariffed are even made in Australia, so it’s not like there would have been any interest group resistance.

But small-fry reform like that won’t exactly solve our productivity crisis: while the tariffs will reportedly save businesses “$30 million a year in compliance costs”, one senses that they were only removed because the government was spending “more administering and complying with the tariff system than we receive in revenue”.

Thankfully, Chalmers wasn’t done there. On a more impactful note, the Treasurer announced “a financial sector regulatory initiatives grid to make sure the standard business of regulation is carried out in a more co-ordinated and coherent way”:

“The grid will provide transparency around the regulatory landscape for the financial sector, giving greater certainty to industry to support engagement with proposed reforms and their implementation.”

That’s an excellent reform and should be rolled out to all government agencies, not just the financial sector’s regulators (ASIC, APRA, and the RBA). In fact, all new regulations should be subject to cost-benefit analysis, if for no other reason than to rule out the absolute worst, productivity-sapping proposals.

But with an election around a year away, I’m not hopeful that we’ll get much more out of this government. I’m happy to be proven wrong, of course, but the sad fact is that spending promises targeted at marginal seats generally sell better than long-term reform, which often come with short-term political costs.

But reform is what we desperately need in this country: Chalmers has called this the “defining decade”, and he’s right. Our anaemic productivity growth over the preceding decade – the lowest for sixty years – will not magically fix itself. Chalmers should lead by example, and that means less dubious industrial policy and more meaningful economic reform.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!