What the US election means for Australia [update]

It’s election day in the US, so I’m re-sending last week’s post on what I thought the most likely implications for Australia were going to be. This time around it’s open to everyone – some issues are just too important to keep behind the paywall!

As for how the season finale of the world’s greatest reality show is tracking, the final polls were so close that they may even be showing signs of “herding”, making them unreliable, or perhaps they’re not and the critics are over-complicating things. Either way, my advice is to beware those presenting numerical models as scientific – they all contain a large dose of subjectivity, and should be weighted accordingly.

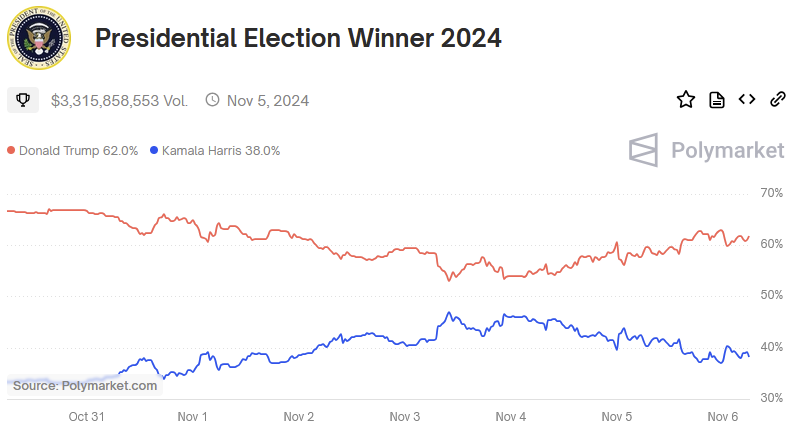

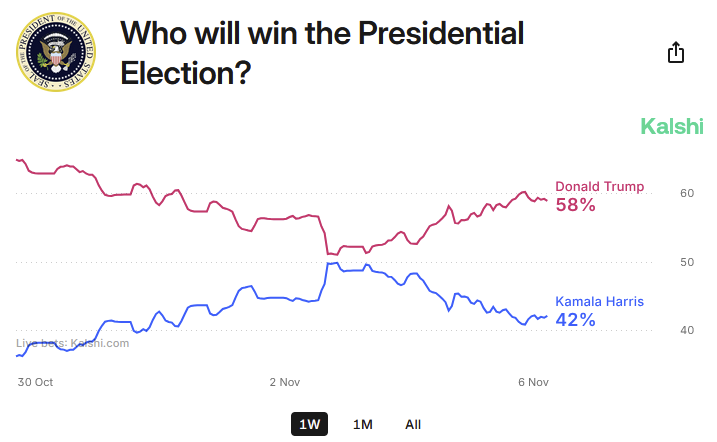

Personally, I ascribe more weight to betting sites – skin in the game, and all that – and after narrowing considerably to the point that it was basically a coin toss over the weekend, they’re currently giving a slight ~60/40 advantage to Trump:

I say “slight”, because while the Trump advantage may seem significant, a 10% change in win probability only corresponds to about a 0.4% swing in the candidates’ predicted vote share.

Basically, it’s still anyone’s election.

But no matter what happens, one thing is for certain: the end of days predictions you’ve been seeing in the media from those who make their living selling fear will be well off the mark.

Yes, it’s true that the US executive (president) is more powerful than it has ever been, so federal elections hold more importance than they ever have. But when you boil it all down, Trump and Harris aren’t too far apart on many issues, and plenty (most?) of their craziest policy ideas won’t ever see the light of day; there are still enough legislative and judicial checks and balances to ensure that the country remains a healthy democracy for a long time to come.

As for what a Trump or Harris Presidency would mean for Australia, read on! For the full context, start with the first half here.

Inflation is dead… or is it

Jesper Rangvid recently analysed the inflation situation in the US, drawing parallels with the 1970s. Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but what it does show is there’s at least one historical episode where a ‘soft landing’ was actually quite bumpy:

Of course, the 1970s were very different to today. For example, there were real shocks (e.g. oil crises) and widespread price controls that distorted the data, making it appear as though inflation was falling when it was still bubbling away in the background – sort of what the Albanese government is doing with its “cost of living” relief, but much more economically damaging.

None of that is happening today (at least not yet), so inflation is unlikely to shoot back up without a policy mistake. On that note, Rangvid warns that there are two risks “that could reignite inflation” in the US:

“First, monetary policy could become overly loose. Markets anticipate a 50-basis-point cut this year and a further 100-125 basis points next year, and Fed governors expect about the same, as revealed by their ‘dot plots’. This comes against the backdrop of a strong underlying economy, as noted earlier. In fact, the strength of the current US economy argues against further interest rate cuts, yet they are still likely to happen. There is a risk that future rate cuts could be too aggressive, potentially reigniting inflation. While this is not my base case—I still expect a soft landing—it is a risk we cannot ignore entirely.

The second risk is political: the upcoming U.S. election. Without delving too deeply into politics, it is fair to say that Trump’s policies, if he wins, could be inflationary. A more politicised Fed (i.e., one that adopts an even more expansionary monetary policy), tariffs, quotas, import levies, and so forth, as well as highly expansionary fiscal policies, all point toward rising inflation. While this would not happen immediately, it is a risk we cannot fully dismiss.”

The US Fed has already cooled on the idea of further rate cuts, so the biggest risk is the second one: the election, and the potential for a sharp deterioration in the federal budget deficit that drives up inflation expectations. That risk would be greater with a Trump presidency given his public statements questioning the need for an independent Fed, and that he believes “the job involves showing up once a month and flipping a coin”.

Trump’s climb up the polls and on betting sites might then explain why US 10-year Treasury yields have risen from around 3.6% to over 4.2% in a month: perhaps people’s expectations of future inflation are rising. Another reason might be rising inflation risk premia, perhaps because the outlook for the US deficit has deteriorated as the candidates’ big-spending policies are revealed without credible plans to pay for them all.

The fact that inflation hedges such as gold have moved up along with bond yields is unusual, and suggests that both of these explanations might have some weight to them (although central banks appear to be meddling).

Whatever the cause, higher yields mean greater borrowing costs for the US government, which will exacerbate its fiscal challenges and could even lead to a debt crisis, financial repression, or the temptation to let inflation rip again.

None of those scenarios are positive for the economic outlook.

Never bet against the yanks

However, despite those uncertainties the US economy retains unique qualities and I would be hard pressed to bet against it.

What matters is the relative economic strength of an economy. The US may not be the capitalist force it once was, but it’s not like the rest of the world has been trucking along the road to libertarianism, either. Europe seems content on regulating itself into economic stasis, while China centrally planned itself into a corner right as its demographic dividend reversed, and all before it managed to get rich.

For all of its political problems, the vast majority of Americans are still free to just get on with it. There’s a reason why America’s share of the world’s stockmarket capitalisation is at an all-time high of 61%, well above its approximately quarter share of global GDP.

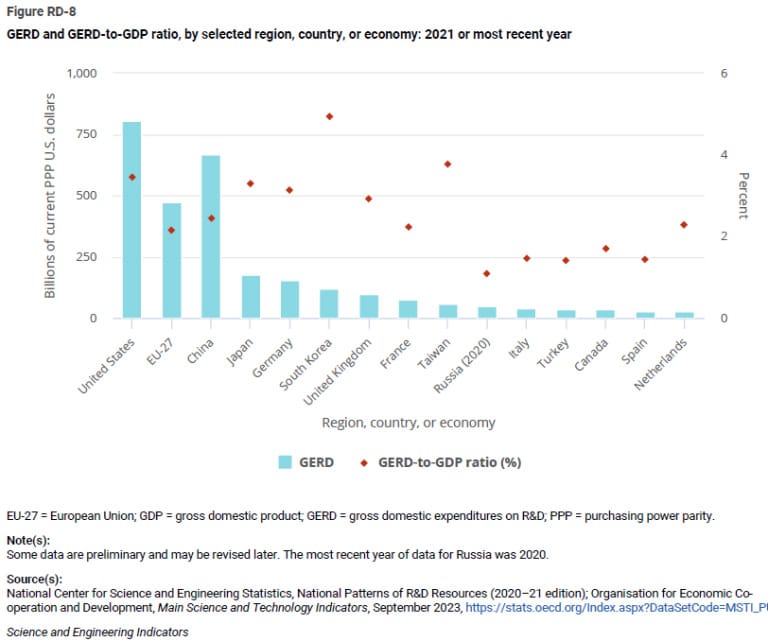

And while its government has dropped the ball on R&D – a key driver of long-run growth and productivity – the private sector has picked up the slack. Today, the US “has both the highest level of absolute R&D spending and also–thanks the recent run-up in R&D spending by business–one of the highest levels of R&D spending as a share of GDP”:

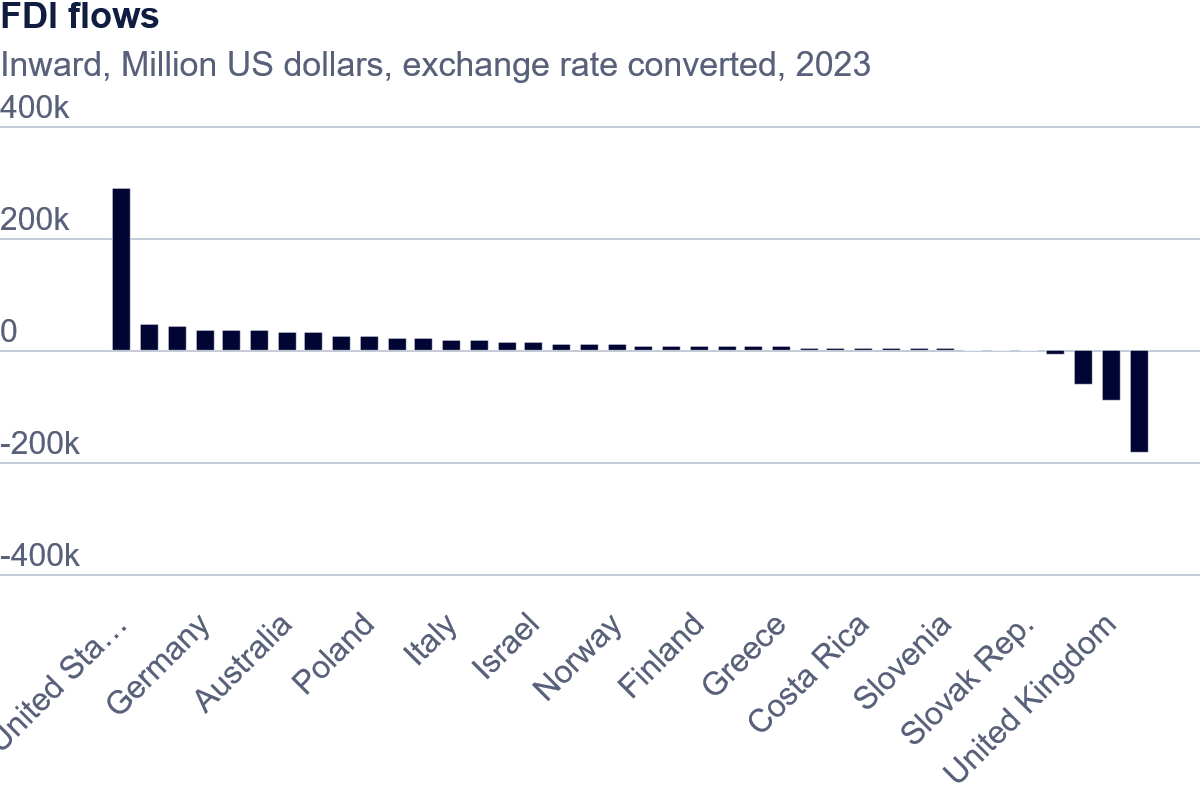

When combined with its institutions – e.g. the rule of law, floating currency, developed financial markets, entrepreneurial culture, relatively stable political system – and its uncanny ability to attract foreign investment, it goes some way to explaining America’s ability to outgrow other advanced economies.

Even when the US doesn’t do the innovating, it’s often the first place that benefits from innovations elsewhere because of its large, relatively free domestic economy. The most recent example was the news that the US may have passed peak obesity, thanks to weight loss drugs such as Ozempic. It was developed in Denmark but the US is where it was first made widespread:

“The US leading the descent is a beautiful twist. Its unparalleled consumer culture sent its obesity rate rising faster and further than almost anywhere else. When the solution was regulation or moderation, America was at a disadvantage. But when procuring and distributing large quantities of pharmaceuticals is the name of the game, the US is unrivalled. These drugs are more widely available there than anywhere else.”

Believe it or not, but the US is also more pro-labour than most other nations, including those in Europe. Not because it has a bunch of regulations “protecting” jobs, but because its relatively de regulated labour markets force businesses to compete for workers, allowing them to capture more of the gains from growth.

By not locking workers into firms it also means the economy is more adaptive: people are more likely to move to where the jobs are. As I wrote a couple of weeks ago in the context of the Albanese government’s labour market reforms:

“If you seek to protect jobs, you reduce mobility and business dynamism – how firms grow and the ability of workers to move between them – both of which are key to productivity growth and the creation of new jobs. If policymakers get the balance wrong, resources will struggle to flow to their most productive uses, ultimately reducing productivity, growth and real wages in the long-run.”

There’s a reason why most European economies are mired in “sclerosis”, and their rigid labour laws are at least one reason why.

So, regardless of who wins the next US election, the sky probably won’t fall in. The country’s institutions are robust enough to withstand another Trump term, and its political system is fragmented enough to block the worst policy proposals of another Biden Harris term.

The US economy is by no means invincible, but its ability to bounce back from adversity is unrivalled. If presented with a true debt crisis, there’s a good chance that the tough political decisions of balancing the budget and reforming entitlements will happen – at the last possible moment!

Implications for Australia

My view is that if Harris wins, we’ll essentially get more of what we’ve had the past four years. That means more wasteful industrial policy and an American economy that will drift closer to the Californian or European model of state capitalism.

Harris is, after all, from one of the most Democratic states in the country, California, and was an early co-sponsor of the Green New Deal and supported Medicare for All (Bernie Sanders’ single-payer healthcare plan) in her 2020 run at the Presidency (she has since claimed to have abandoned both).

If Trump wins, I expect much more policy uncertainty, even broader tariffs, and an escalation of global geopolitical tensions. How that all works out depends on how heavily you weight the effectiveness of the madman theory of foreign policy, because that’s basically Trump’s approach to making “deals”.

But no matter who wins they’re probably going to struggle to get their most damaging policy ideas through a divided Congress without negotiation. That applies more to Harris than Trump, as a Republican victory would probably also see enough of the Senate flip to give the Republicans a majority.

That’s not all bad. Empirically, having more Republicans in Congress is better for most “libertarian concerns”, which are generally the ones I resonate with and for me at least makes them “the lesser evil” of the two parties.

However, the ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA) faction is not exactly aligned with many traditional Republican positions – Trump is nowhere near where history’s median Republican would stand on most issues! That could leave a future President Trump with even fewer traditional Republican checks on his craziest ideas, let alone Democratic ones. So, while Trump probably has the higher potential economic upside of the two candidates, that needs to be weighted against the very significant risks of a Trump government becoming completely unhinged.

All up, a small Harris victory with a Republican Congress might be the closest thing to a “win” in the context of this Presidential race, in which we’re all losers to some extent.

Trade wars are coming no matter who wins

One thing Congress cannot stop is tariffs, a protectionist trend the Biden/Harris government has also embraced. Thankfully, tariffs are economically destructive principally to the US and to the countries that retaliate (of course Europe already has plans drawn up; they truly are experts at self-flagellation).

As a small, open economy, with few politically-sensitive industries lobbying for protection, Australia will hopefully stay out of any tit-for-tat trade war and instead welcome the more affordable goods that will inevitably flow our way as other avenues are sealed off.

For example, Mitsubishi Motors Australia chief executive Shaun Westcott recently predicted a “bloodbath” in the auto sector:

“Our country doesn’t have an industry to protect, everyone thinks this is the place to be, we don’t have any tariffs, we don’t have any barriers. There’s going to be a plethora of new brands who have economic troubles, where they have excess capacity, they will look for places to dump their cars. We’re going to go into a period of excess supply, and not everybody will survive that, and there’s going to be a bit of a bloodbath.”

A bloodbath for producers means riches for consumers. Recent modelling from the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggested that Australia would be one of the chief beneficiaries of Trump’s most extreme anti-trade and immigrant policies, gaining a full percentage point of GDP by 2028 if he’s able to go full-craze.

Basically, if Trump wins and everyone starts whacking tariffs on each other and debasing their currencies, and Australia does a Switzerland and stays out of it, a lot of desperate producers will look to us to absorb their “excess supply” – at bargain basement prices!

It’s during times like these I’m just thankful that we don’t make geopolitically sensitive goods like cars any more, because I’m certain that if we did, Albo would have tweeted something similar to this by now:

Regardless of who wins next week Australia will probably be just fine, because the forces that lead politicians to pass stupid, anti-consumer policies like Trump, Biden and Trudeau’s tariffs are more limited here in Australia. So, we’re more likely to stay open for business and will therefore be free to enjoy the bounty of imported goods that might soon be looking for a new home.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!