What's up with Canada?

I’m back from the Canadian wilderness and it sure seems there’s plenty to write about, not least Friday’s embarrassing (for all) first US Presidential debate which, if betting odds or prediction sites are to be believed, has all but assured a second Trump term in November.

But given that today is Canada Day, I thought I’d kick the week off with a look at our distant Commonwealth cousin’s economy. As an outsider I’m inevitably going to get some things wrong, and what follows is by no means comprehensive. Believe it or not but I don’t mention housing once, mostly because Canada’s problems there are so similar to our own that I didn’t think it would add much value to this post.

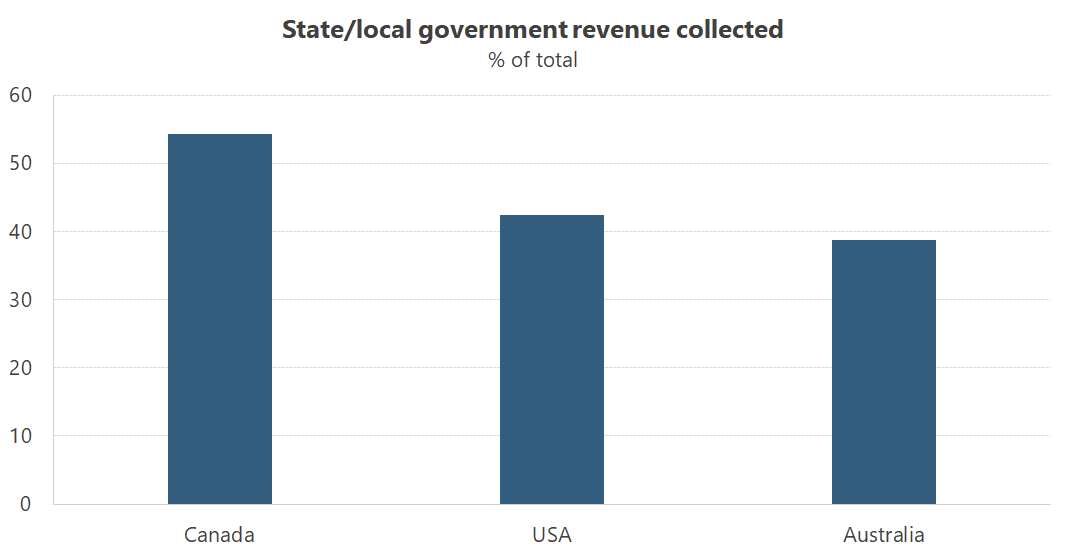

Anyway, perhaps the first thing you need to know about Canada from an Australian perspective is that despite a similar British heritage, Canada has a very different constitution to ours. For example, Canada’s provinces and its federal government can levy their own income, company, and consumption taxes (e.g. GST). It makes for a mildly annoying shopping experience but also means that in Canada, the provinces and local governments have considerable revenue-raising powers.

Somewhat ironically, that’s precisely the opposite of what was intended at the drafting of Canada’s constitution. As Canada’s first Prime Minister John A. Macdonald wrote prior to confederation:

“We must reverse this process [of decentralisation] by strengthening the General Government and conferring on the Provincial bodies only such powers as may be required for local purposes.”

Macdonald was wary of the American model which had empowered its states and contributed to the Civil War, so the Canadian constitution was drafted with the intent to, over time, “extinguish the independent existence of the several Provinces”.

But over time the balance of power shifted – largely due to judicial action – and today “of the unit governments in the three Anglo-American federations (Canada, Australia and the US) the Canadian provinces are by far the most powerful”.

Unlike Australia, Canada’s constitution doesn’t guarantee free trade within Canada; as a result, it is often “easier for Canadian companies to do business across international borders than it is within our own country”:

“[S]ection 121 of the Constitution Act seems to clearly require the free movement of goods among provinces, but the Supreme Court of Canada has, out of respect for provinces’ rights, deferred to the notion of federalism and consistently interpreted legislation in a way that permits provinces to put limits on trade.”

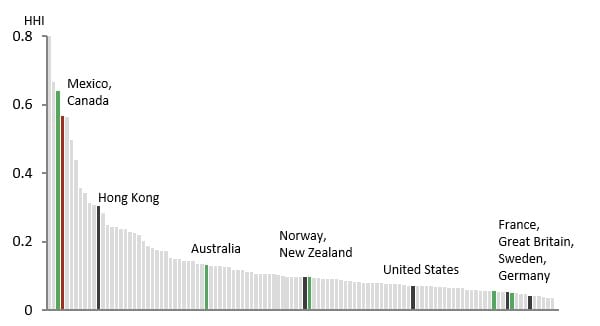

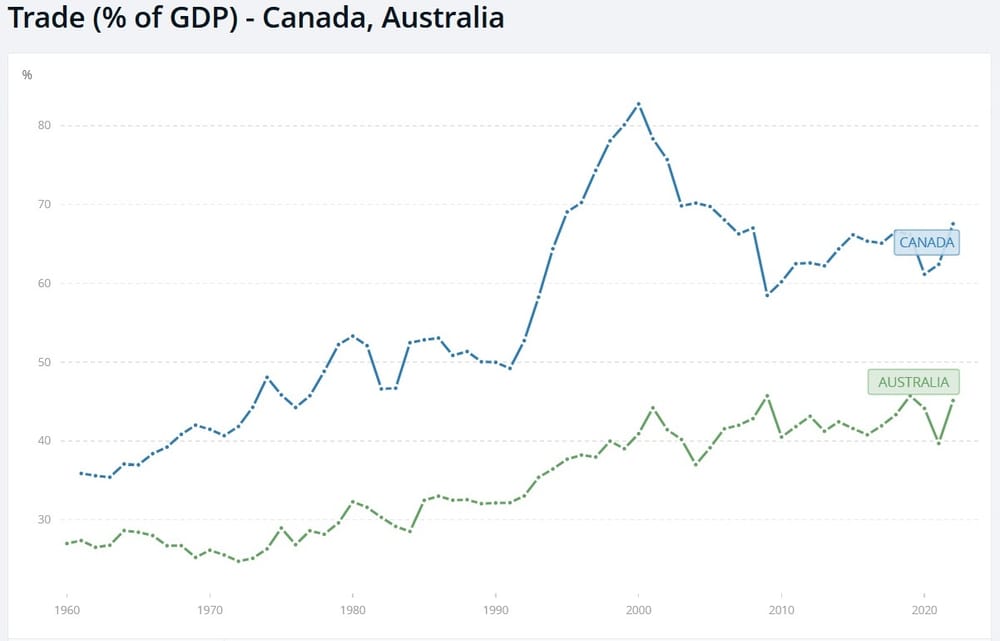

Some 90% of Canadians live within 250km of the US border and that proximity, combined with the ease of trade thanks to various national agreements, means that around 50% of its imports and 75% of its exports are from/to the US. In a global context, Canada’s trade is one of the most concentrated, behind only Kuwait, Bermuda, and Mexico.

That dependency, along with Canada’s relatively protectionist inter-provincial rules, has materially shaped its development. While provincial strength and competition for people and capital between them could – at least in theory – create mutually beneficial gains, in Canada the provinces are more likely to use their power to engage in zero (or negative) sum games by erecting various barriers to prevent that from happening.

The two Canada’s

I like to think of Canada as two countries. Not English/French, but as a highly protectionist and free trading country. I often look at Australia and lament the obvious protections our politicians give to unworthy monopolists ( cough Qantas cough), but Canada takes that game to another level. In fact, most of Canada’s major corporations are basically oligopolists:

“For example, the Big Six banks control about 95 per cent of the banking industry. BCE Inc., Telus Corp. and Rogers Communications Inc. account for 88.7 per cent of the telecom market. Air Canada and WestJet Airlines Ltd. command more than 85 per cent of their industry. And you are most likely to do your grocery shopping at Loblaw Cos. Inc., Metro Inc., Empire Co. Ltd., Wal-Mart Canada Corp. or Costco Wholesale Canada Ltd., which command over 60 per cent of the grocery market.

As a result, much of our consumer market offers the theatrics of choice, with many of the participating retailers being sheltered under the umbrella of these large corporations.”

Why aren’t large US companies moving in and capturing some of those monopoly rents? Because various laws protect the incumbents from that threat, whether it be property controls that make it “difficult, or even impossible, for businesses to open new stores”, or ownership limits and cabotage rules that prevent foreign firms competing with the locals.

Past attempts at liberalising trade within Canada have only been agreed by the provinces when they include “negative lists, which has enabled provinces to identify various exceptions that were excluded from coverage”.

Such lists are just one method of protecting the country’s various cartels, from dairy to maple syrup, which donate heavily to politicians left and right. Google defines a cartel as “an association of manufacturers or suppliers with the purpose of maintaining prices at a high level and restricting competition”, and Canada sure has a lot of them. Some are so powerful that they, with the government’s permission, are allowed to set limits to how much dairy, chicken, egg, and turkey can be produced, with production quotas allocated “to a tight-knit inner circle of dairy farmers”.

The result of this protectionism is that Canadians pay significant more for many goods than Americans just south of the border (there are over 1.5 million same-day trips made from Canada to the US each month, so there’s probably plenty of people driving south to do their shopping, eroding Canada’s domestic economy).

Dairy protection alone drives up prices for households by more than C$500 per year, and is one reason why we pay around A$1.50 per litre of milk in Australia but Canadians get slugged C$2.92. It’s a “highly regressive” policy, i.e. it disproportionately affects the poorest households, but it persists because politicians prefer forcing households to pay higher prices than directly subsidising farmers, which is politically more difficult and restricts their spending elsewhere.

But none of this is to say Canada is bad at everything; its rent seekers just take other forms to those in Australia, with inefficiencies in different places. For example, in Canada there are no silly 1.5-10km " Location Rules" that protect existing pharmacies from competition, and " it is clear that [Canadian] pharmacies operate in a highly competitive market".

Household electricity prices in Canada are also around half what they are in Australia. Energy use is highly correlated with income growth, so perhaps that – along with its proximity and relative free trade with the US – is how Canada has ‘got by’ and maintained reasonable living standards despite domestic protectionism raising the prices of many household goods.

Canada has an investment problem

A recent report by the Canadian government found that “investment per worker declined by 20% from 2006 to 2021”, in part due to “an increase in industry concentration and a decline in firm entry rates”.

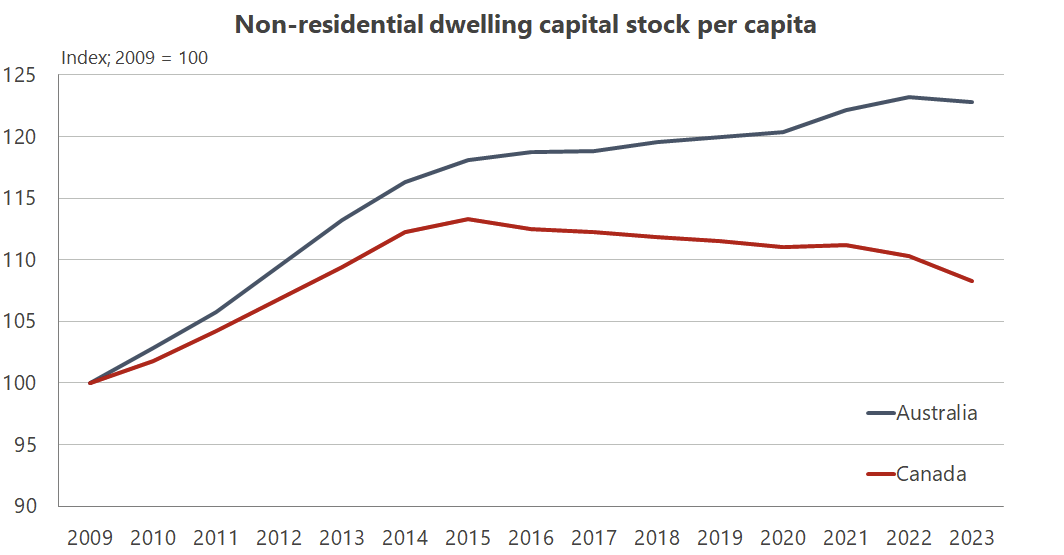

The post-financial crisis mining booms in Australia and Canada both went bust around 2015. But unlike Australia, Canada’s capital stock per worker never recovered and actually started to decline.

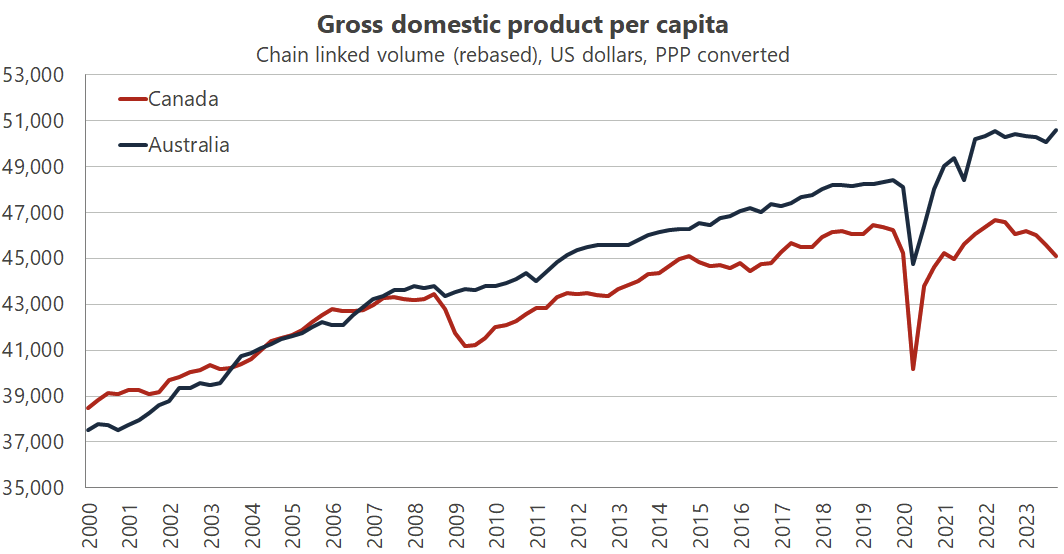

Capital is an essential ingredient for labour productivity and real incomes, so the fall is surely one reason why Canada’s real GDP per capita has underperformed the likes of Australia, where investment has kept pace with the population (although perhaps a bad omen for the future, in 2023 it declined for the first time since at least 1970).

A recent report by the National Bank of Canada cautioned that Canada was “caught in a population trap that has historically been the preserve of emerging economies”:

“Simply put, Canada is in a population trap for the first time in modern history. More worrisome is the fact that the decline is not simply due to a lack of housing infrastructure. In fact, the private non-residential capital stock to population ratio has been declining for seven years and is currently no higher than it was in 2012.”

Essentially, Canada’s economy is tangled up with domestic obstructions to trade and investment, making it difficult to boost productivity.

Canada is vulnerable

Canada’s per capita household spending contracted in 2023, with declines in business investment and inventory accumulation also detracting from growth. The only reason it avoided an outright recession in 2023 was because of net exports “supported by a strong US economy”. But the US economy is being juiced by federal budget deficits of ~6.7% of GDP, which is clearly unsustainable. If growth slows, Canada would be in trouble.

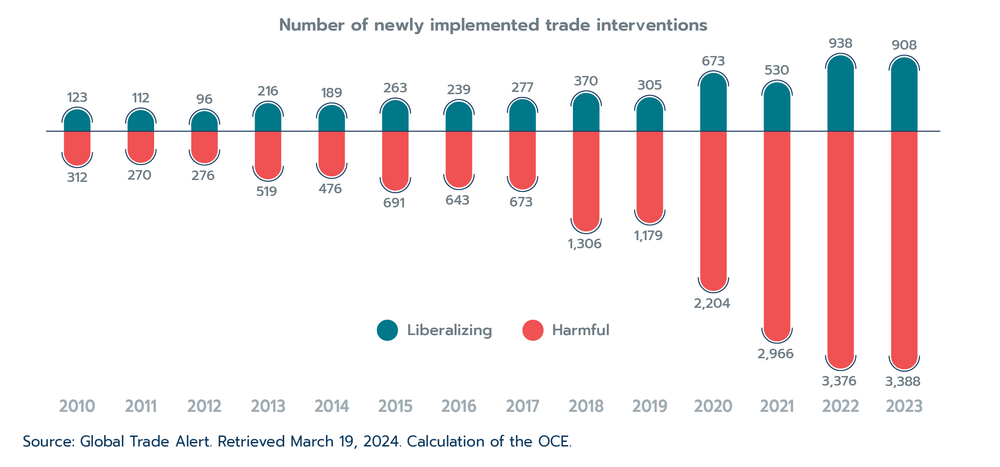

Another key risk for Canada (and Australia!) is the rise in global protectionism. The Biden administration has escalated the US war on trade, and a 2025 Trump administration would almost certainly accelerate it even further. That has triggered retaliation, with global trade interventions rising steadily since 2018.

Despite being ‘friends’, Canada is not immune: the US imposed tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminium exports in 2018, and it could be the target of future action given that Canada runs persistent trade deficits with the US and Trump erroneously believes that means they’re “winning” and need to be stopped. With roughly 1 in 6 Canadian jobs linked to exports and a gummed-up domestic economy, trade disputes would seriously harm living standards in Canada.

Canada’s slippery slope

According to the Bank of Canada, “by 2022, Canadian productivity had fallen to just 71% of that of the United States. Over this same period of time, Canada also fell behind our G7 peers, with only Italy seeing a larger decline in productivity relative to the United States”:

“Canada’s economy features many sectors where companies face limited levels of competition, whether from firms in other provinces, foreign rivals or new entrants. Of course, every country has certain sectors that it champions, and there can be valid reasons to protect local businesses. However, too much protection can lead to problems. It can also help to explain Canada’s weak record in business investment.”

Estimates by the IMF ( 2019) suggest that Canadian GDP would increase by up to 4% – C$92 billion – if domestic trade in goods were completely liberalised.

Every. Single. Year.

For a country that over the last decade has experienced its worst real per capita GDP growth since the 1930s, I don’t need to tell you that’s a big deal!

If Canada wants to right the proverbial ship, it needs to get its domestic house in order. But that won’t be easy; one reason why cartels and other protection persists is because removing it would step on the toes of firms and workers that benefit from the current regime of restricting supply to keep prices higher than they would otherwise be. Those beneficiaries tend to be concentrated and profitable, making them very capable of organising political campaigns (lobbying) to prevent any change.

For example, Canada manufactures just 4.4% of textile and clothing products used by Canadians. Yet imported clothing is charged duties of between 16-18%. Consumers only pay a little extra for every shirt, so it’s not worth their time to organise against such blatant rorts. But politicians love the revenue, and the ~35,000 mostly Montreal-based clothing workers (0.17% of total employment) certainly aren’t going to want it removed. The inefficiencies persist.

But alas, despite its huge dependency on international trade and that ensuring trade remains as free as possible is vital to Canada’s interests, it appears to be jumping on the industrial policy / protectionism bandwagon. Just last week, the federal government announced “a 30-day consultation period to examine Beijing’s trade practices in the EV sector”:

“Canadian auto workers, and the auto sector… are facing unfair competition from China’s intentional, state-directed policy of overcapacity that is undermining Canada’s EV sector’s ability to compete in domestic and global markets.”

It’s times like these where I’m especially thankful that we don’t make cars in Australia any more. But for Canada and its many oligopolies and cartels, it’s on a slippery slope: it can either tear down some of its domestic protections, helping to insulate its economy from a potential global trade war and reduce the cost of living for a majority of households, or it can erect even more walls at the expense of future growth and incomes.

Only one of those options will improve long-run living standards for Canadians. But given the current situation I’m not so sure that, when push comes to shove, it’s the option Canada will choose. If so, policymakers in Australia would do well to watch and learn from the Canadian experience over the next several years.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!