When will interest rates start coming down?

I don’t pretend to have a crystal ball, and economic forecasting is generally a game I try to avoid: there are just too many moving parts, also known as people, that make independent decisions and will inevitably ruin any forecast. But what I can do is look at the data and make some inferences about the kind of things that might happen. And one question on everyone’s mind lately is: when is the RBA likely to start cutting the cash rate?

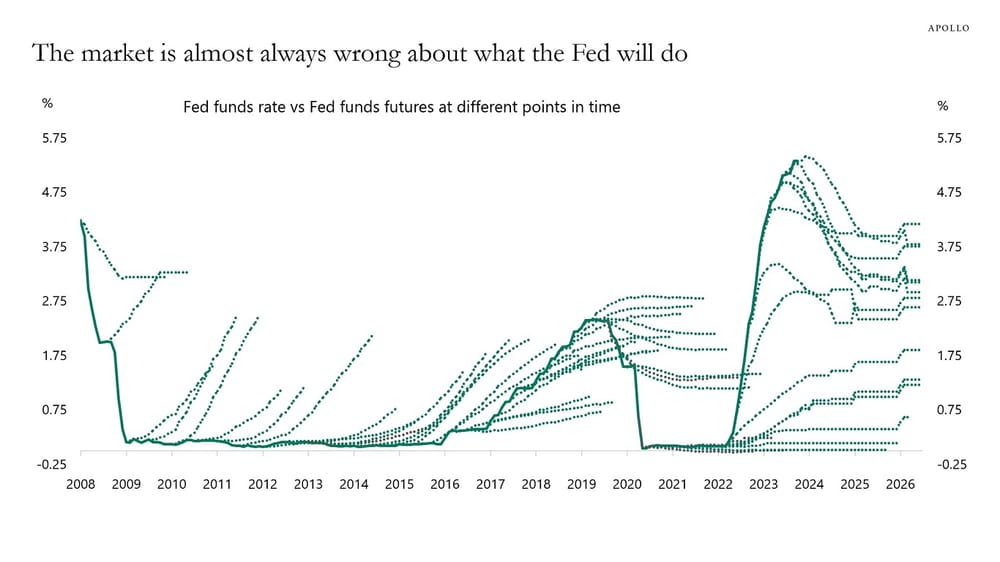

To answer that question, we need to know what a handful of people sitting on the board of the RBA will be thinking at some point in the distant future. One way of doing that is to look at futures contracts – surely people betting with their own money, those who truly have skin in the game, will be more accurate than your average Joe? In Australia, futures markets are currently pricing in a 25 basis point rate cut by around Sep-Oct 2024, but clearly a lot can change in that time. I personally wouldn’t put much weight on these ‘forecasts’; markets are simply pricing in the balance of probabilities, given the current stock of knowledge. They can be, and frequently are, wrong.

Futures are better thought of as market hedges than forecasts.

Futures are better thought of as market hedges than forecasts.

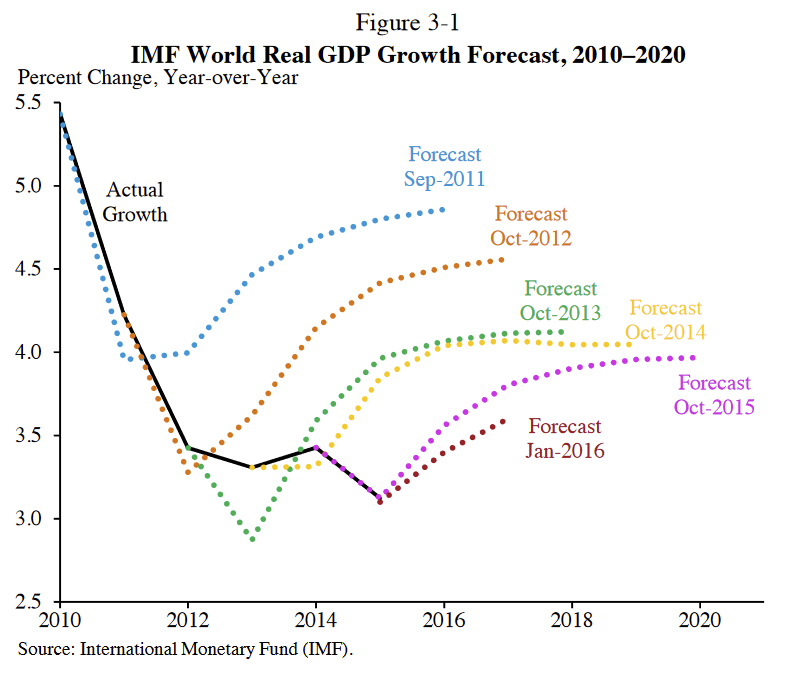

Another way of trying to peer into the inner workings of the RBA is to look at what professional forecasters are saying. Last week, the IMF released its latest “projections” for Australia, which predicted an average cash rate of 4.4% in 2024 (presumably rounded up from the current 4.35%) – i.e., it’s expecting no movements this year, or more hikes followed by cuts that average out to the same. But the IMF is almost always wrong, too.

The IMF generally assumes some reversion to a long-run average.

The IMF generally assumes some reversion to a long-run average.

A third method is to look at betting markets. While the likes of Kalshi don’t cover Australia (we’re just not that important), they do make markets for US interest rates. And just this year (so, 21 days), punters have gone from expecting 6 rate cuts to 5 in 2024, and the odds of a March cut has fallen from nearly 70% to just 35%.

Essentially none of the methods I mentioned above is even close to being average at predicting macroeconomic events such as the timing of cash rate decisions. But all is not lost – rather than make a forecast, sometimes it’s helpful to look at what has already happened in other parts of the world, where conditions moved more quickly or slowly than in Australia for various reasons, and whether or not that might be applicable Down Under.

Evidence from abroad

Following the pandemic, Australia was slow to the rate hike game. Inflation started to increase a bit later here than in other countries, and the RBA sat on its hands for longer than many of its international peers before tightening monetary policy. If that pattern holds in the other direction, too, then overseas economies could be a decent canary in the coalmine, so to speak.

Now your immediate temptation might be to look at the world’s largest economy, the United States. But before you go looking for the latest Wall Street Journal, the US is not one of the countries I think we should be watching for local insights, for a few reasons. First, it’s the world’s largest economy and the dollar is the de facto global reserve currency. That creates unique dynamics that just aren’t found elsewhere. For example, when global uncertainty increases, capital tends to flow into the US, depressing interest rates and strengthening the dollar. If anything, the opposite happens here.

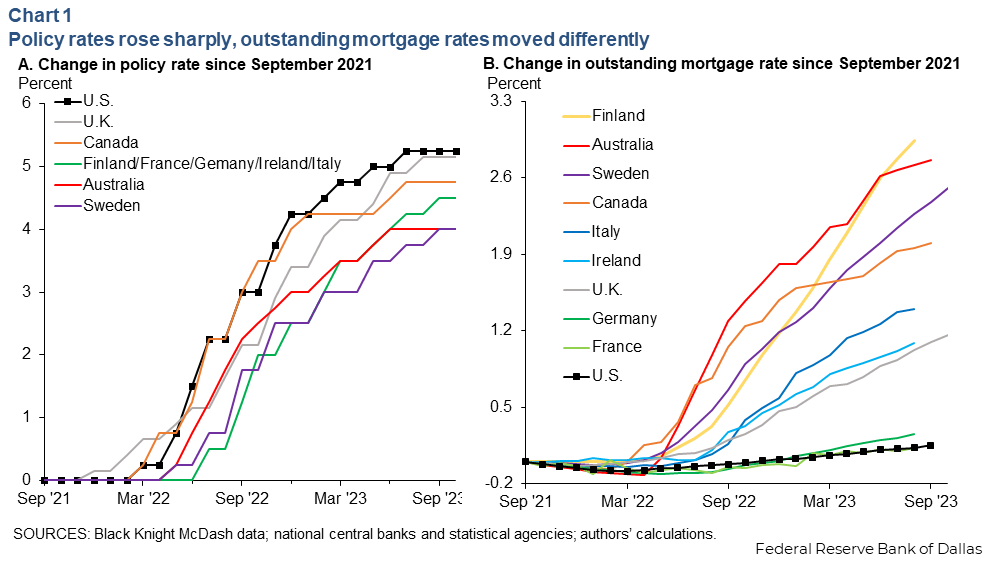

Second, a key transmission mechanism of interest rate changes in Australia is mortgages, and the US mortgage market is odd. Through a complex system of regulation and cross-subsidies dating back to the Great Depression, most homeowners in the US have long-term (30-year) fixed mortgages. When interest rates rise, the effect is felt mostly by businesses and how it restricts labour mobility, rather than household consumption – you’re not likely to take a new job on the other side of the country and buy a new home, without a significant pay rise, if it means changing from a 2.5% mortgage to one above 7.0%.

Higher interest rates transmit much more quickly through to consumption in Australia, where mortgages are predominately variable. We can clearly see that difference in the data, courtesy of the Dallas Fed.

Enter the Canucks

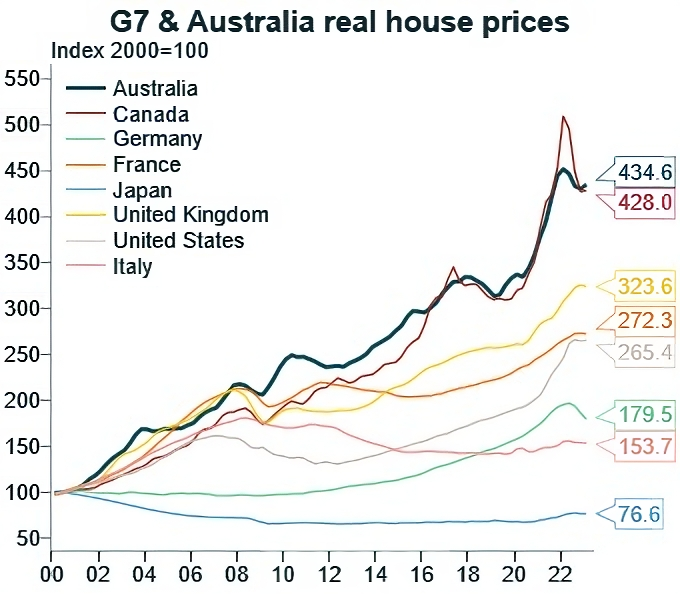

Eyeballing the above chart, the country most like Australia – but one which hiked rates much earlier – looks to be Canada. Our Commonwealth cousin also ticks a few other boxes, such as runaway house prices.

Australia and Canada’s houses are very, very expensive.

Australia and Canada’s houses are very, very expensive.

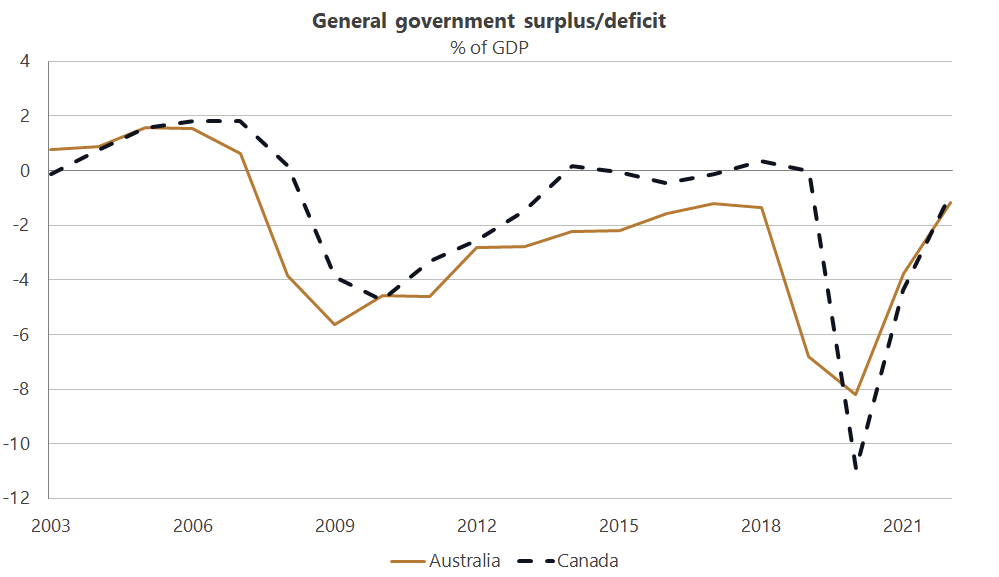

The Canadian government also spent like a drunken sailor during COVID, so the fiscal contribution to inflation should have been similar.

Our governments spent at very similar rates.

Our governments spent at very similar rates.

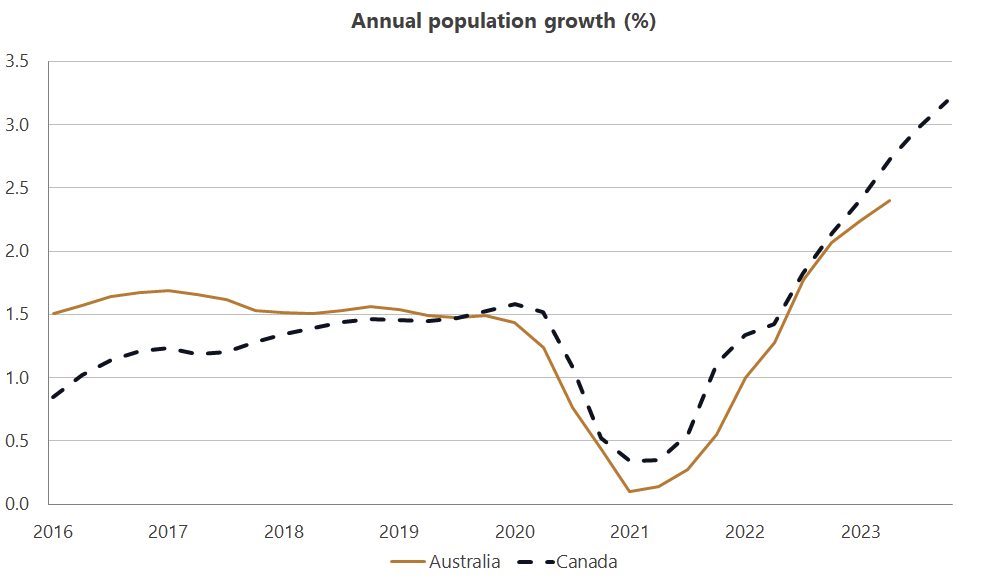

Last but not least, Canada has also experienced rapid population growth in the post-pandemic era.

Population growth is being fuelled by migrants to both countries, specifically students, who tend to put upward pressure on inflation in the short-run.

Population growth is being fuelled by migrants to both countries, specifically students, who tend to put upward pressure on inflation in the short-run.

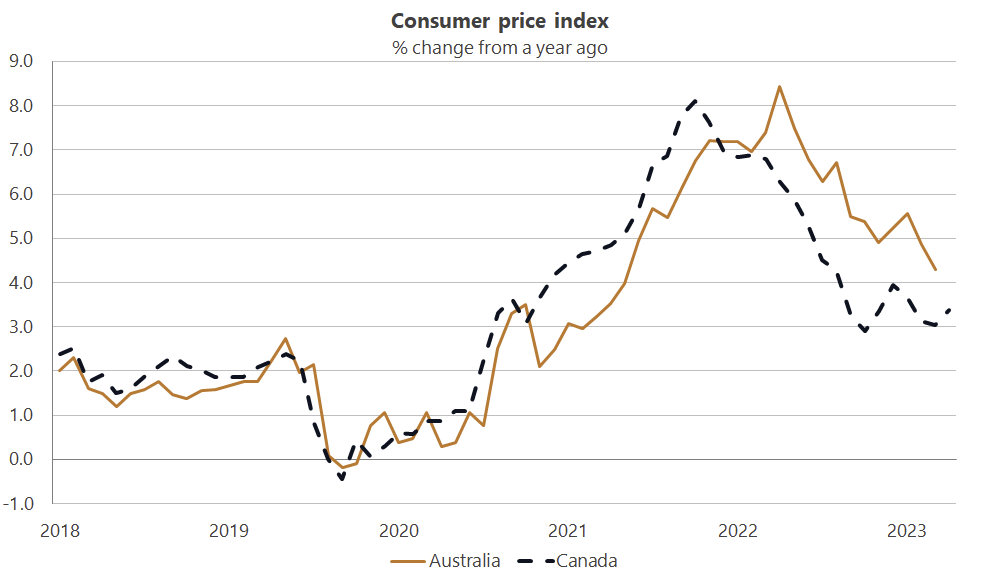

Ok, so we have a few things in common. But the pertinent question is how did Canada compare to Australia in terms of inflation, which is clearly the most important indicator for our respective central bankers when considering whether to cut (or hike) interest rates. Let’s take a look.

We’re missing a couple of months’ worth of data for Australia because even our statisticians are a bit late down here.

We’re missing a couple of months’ worth of data for Australia because even our statisticians are a bit late down here.

We can see that Australia and Canada broadly tracked each other until July 2021, when Canada’s CPI shot up but Australia’s collapsed. The reason? Over half of Australia was suddenly locked down.

“As outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant which started in June 2021 in New South Wales spread, almost half of Australia’s population and most major cities were in lockdown for at least 3 days during July 2021. The outbreak worsened in New South Wales and spread to Victoria in the following weeks causing new record daily cases in both… Lockdowns were phased out after 70% of the population was vaccinated in October with most public health restrictions removed after vaccinating 90% of its population in December 2021.”

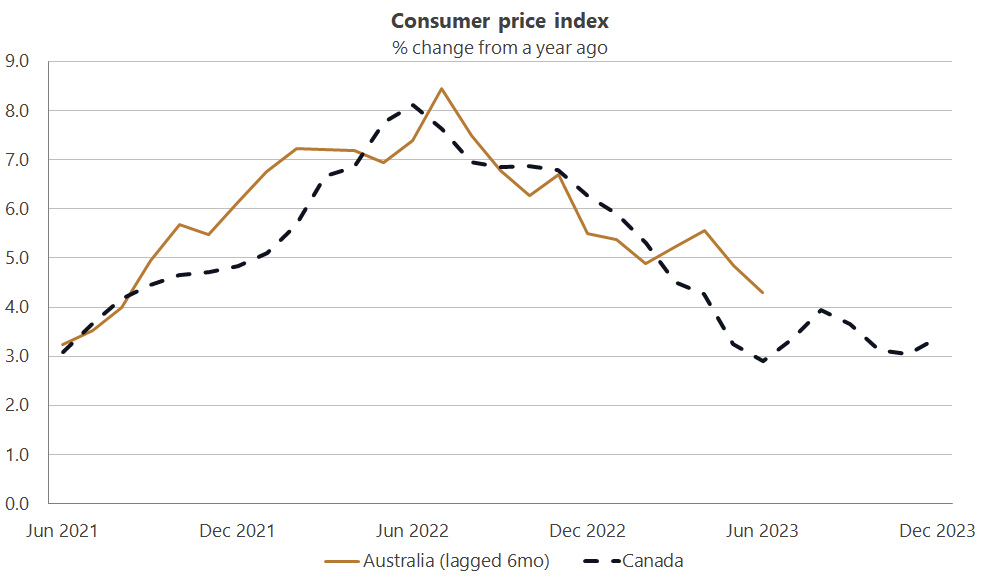

It’s hard to spend when you’re trapped in your house! But the fiscal and monetary ammunition had already been fired, with the lockdowns only delaying inflation’s grip on Australia. If we show the same chart but with Australia lagging Canada by 6 months from July 2021, the two line up reasonably well.

Inflation in Canada has stabilised well above its central bank’s target.

Inflation in Canada has stabilised well above its central bank’s target.

For those hoping a rate cut might happen sometime soon, I have some bad news: Canada’s rate of inflation has stabilised above 3% – well above the Bank of Canada’s (BOC) 2% target – despite the central bank holding the cash rate at 5% for the past six months. In December, the BOC warned that even with the slowdown in consumption and flat investment activity, which led to an economic contraction in the September quarter, it is “still concerned about risks to the outlook for inflation and remains prepared to raise the policy rate further if needed”.

Looking ahead

If Australia follows the Canadian path, then inflation could prove to be stubborn for several months to come. The much-celebrated decline in the rate of Australia’s inflation in November is not entirely what it seems: a decent chunk of the slowdown was due to temporary government support, which will have the opposite effect on the data in a year’s time. Not only does that kind of support – e.g., artificially suppressing energy prices – do nothing to quell inflation (like all price controls, it just distorts measured inflation), it also tends to make inflation worse, because it dulls the ability of prices to ration demand. If prices appear to have come down, people have less of an incentive to reduce their consumption of whatever good or service the government has meddled with.

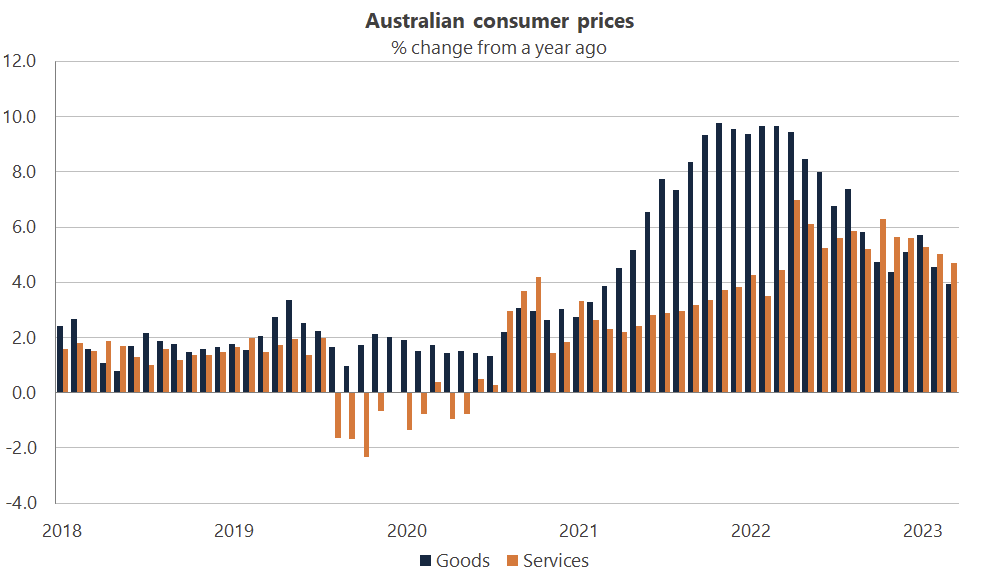

But there is good news! When we break the data down into their two main subcomponents, goods and services, we can see that most of the inflation is now coming from services. That means that the easing of global supply constraints has flowed through to Australia.

Services inflation may not come down as quickly as goods inflation has.

Services inflation may not come down as quickly as goods inflation has.

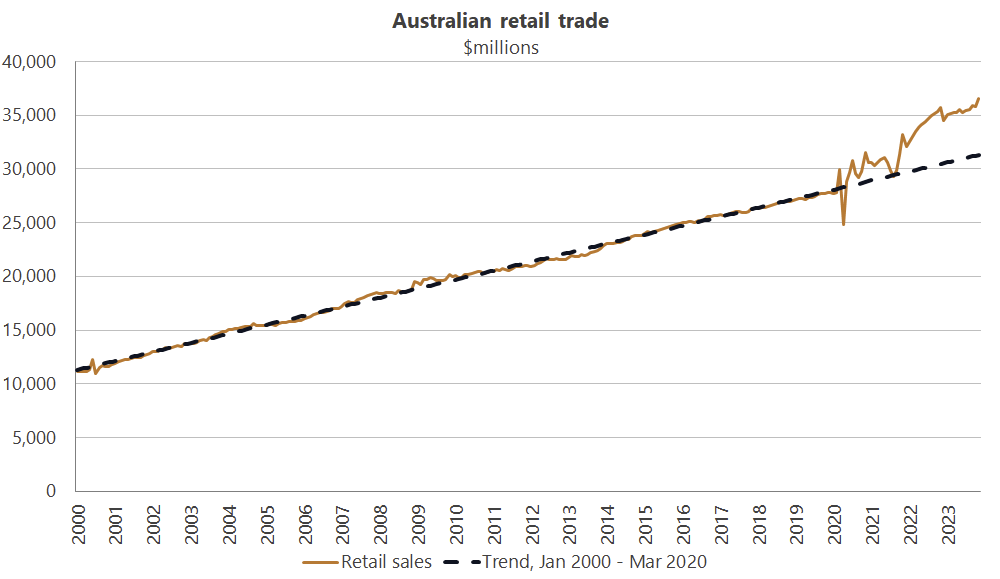

The bad news is that services inflation tends to be stickier than goods inflation: we’re a services-heavy economy (something like 80% of production is in services), and nominal wages are growing at over 4% annually. It’s going to be hard for services inflation to come off the boil without a material slowdown in consumption and inflation expectations, the latter of which is still suggesting inflation of around 4.5% a year from now. As for consumption… well, it’s pretty clear that the pandemic stimulus money supercharged demand and has so far shown no real signs of easing.

Ladies and Gentlemen, this is what demand stimulus looks like.

Ladies and Gentlemen, this is what demand stimulus looks like.

They’re only human

To wrap this one up, I think inflation might stay above the RBA’s 2-3% target for some time yet, which means we’re not likely to see rate cuts anytime soon – perhaps not even this year. While indicators such as employment have come off the boil slightly, the strength of demand in areas such as retail trade and housing, along with the inevitable stickiness of services inflation, means it would probably take a major economic shock for the RBA to cut rates in 2024.

There’s also a risk that we could get slugged with yet another shock in the other direction, such as rising oil prices from tensions in the Middle East, or attacks on cargo ships driving up transport costs and creating supply chain issues all over again. Any or all of those would cause measured inflation to tick right back up, delaying a possible rate cut.

When thinking about the cash rate, you must remember that the people at the RBA are only human, and they don’t want to end up egg on their face all over again by claiming to have conquered inflation, only for it to rear its ugly head right back up. They will be cautious, erring on the side of maintaining rates at their current levels for longer than necessary, even if it risks a short recession.

If our governments want to see rates come back down, they should heed the advice of the IMF and resist the temptation to make matters worse.

“The Commonwealth Government and state and territory governments should implement public investment projects at a more measured and coordinated pace, given supply constraints, to alleviate inflationary pressures and support the RBA’s disinflation efforts. Over the medium term, the governments need to reduce structural deficits and promote economic efficiency. All levels of government need to improve expenditure outcomes and contain structural spending growth.”

In other words, our governments really need to stop aggravating the cost of living crisis by spending as if we’re in a recession. Any support should be narrow and “well-targeted”, and we really need to start doing the hard yards towards economic reform, like, yesterday. Alas, if the ABC’s coverage of Labor’s ‘cost of living’ early caucus this Wednesday is to be believed, it looks like we might be about to get precisely the opposite of that.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!