Where's the efficiency?

It’s all happening in the world’s two largest economies, with Joe Biden ending his candidacy for a second term and China’s Third Plenum (5-year plan) wrapping up, all on the same day. I’ll cover both of those later this week but for now I want to discuss an issue a bit closer to home: economic efficiency and what it might mean for interest rates, employment, and growth in Australia.

Last week the chair of the Productivity Commission, Danielle Wood, was asked whether the health care sector’s growing share of the economy would impact productivity, which regular readers will know is the key long-run driver of real wages growth. Her answer was a resounding yes:

“So what that means is as those sectors expand as a share of the economy, as they inevitably will, that will drive down productivity overall, and you have got to work harder elsewhere.”

Wood knows her economics: what she’s describing is the Baumol effect, named after economist William Baumol who wrote several papers on the issue. It’s not necessarily a bad thing that, as we’ve got wealthier, we’ve decided to spend more on labour-intensive services such as health care. Although the fact that health care is largely government funded, i.e. its relative scarcity (price) is not visible to consumers, means demand tends to be stronger than it would otherwise be.

But it also means there are fewer sources of very productive activity supporting a much larger pool of work where there’s limited scope to raise productivity. What’s especially interesting is how quickly low-productivity sectors such as health care have been expanding in recent years. CBA’s Gareth Aird, for example, recently pointed out that our unusually tight labour market (compared to the historical trend and global peers) might be almost entirely explained by increased government spending on a single item – the NDIS:

“Almost all of the growth in employment over the past year has been in the non-market sector (largely health and social assistance, public administration and education). The big increase of spending on the NDIS in particular has supported non-market sector employment.

In contrast, market employment, where outcomes are strongly linked to the business cycle, has seen essentially no growth over the past year.

Our expectation is that non-market sector employment growth will slow from here. And that will pull the overall rate of employment growth lower and push the unemployment rate higher.”

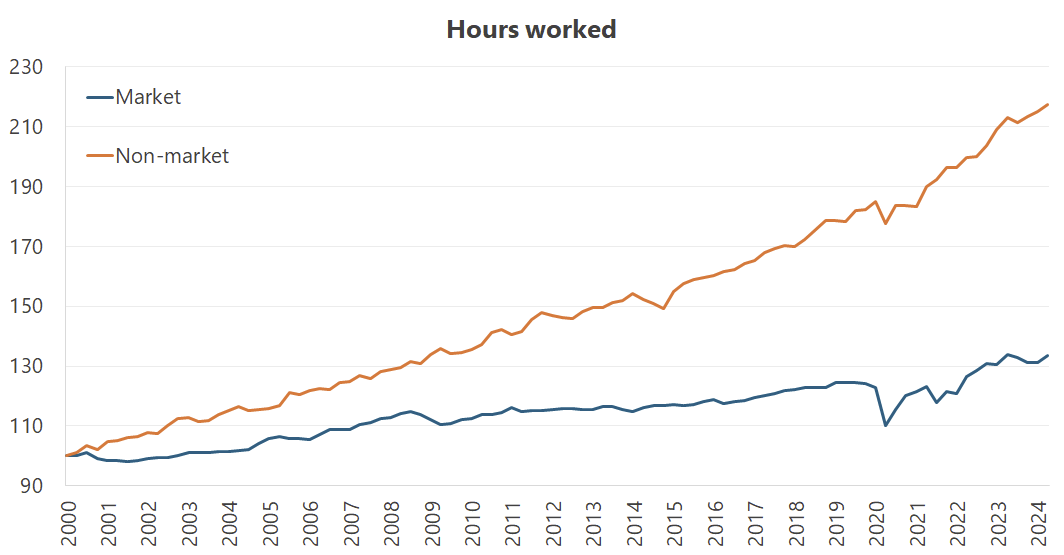

I took a look at the latest employment report and Aird’s claim seems accurate enough: over the past year, market hours worked have fallen 0.3%, while non-market hours worked are up 2.1%.

But while that difference between the two has been especially large in recent years, it’s part of a longer-run trend: non-market work such as health care really has been soaking up an awful lot of labour. Since 2000, non-market hours worked have increased by 117.4%, while market hours worked are up just 33.6%.

Index, Mar 2000=100

Index, Mar 2000=100

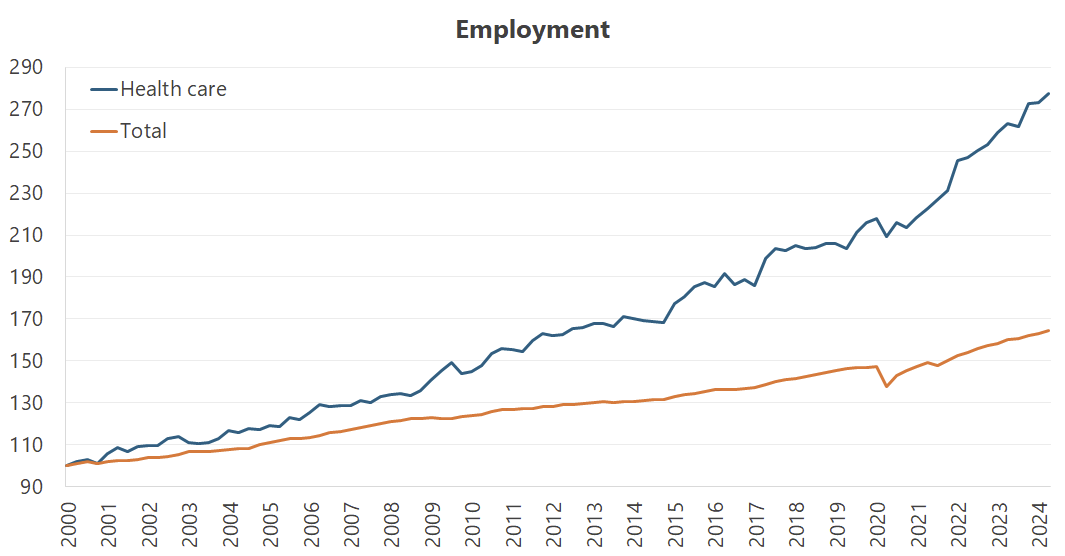

It means the share of work that’s being done in non-market sectors is now nearly 30%, up from around 20% in 2000. And a lot of that is going into health care: as a share of total employment, health care sits at 15.8%, up from 9.5% in 2000 and 12.6% in 2015.

Index, Feb 2000=100

Index, Feb 2000=100

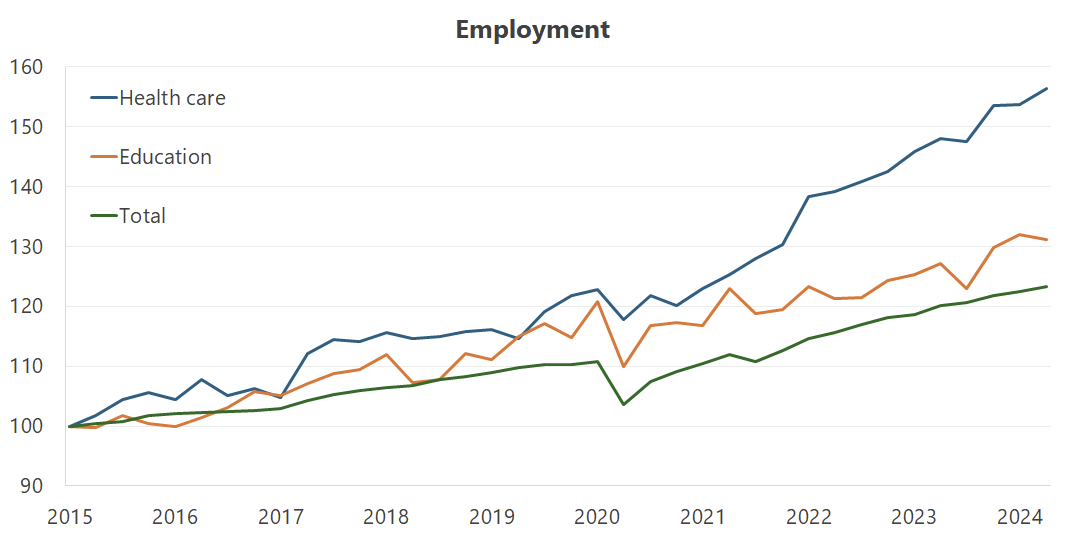

You might think that the expansion of health care is because we’re getting older. More older people, more nurses and doctors needed to maintain standards. That’s true of course, but Australia also has more people working in education than ever before, a sector that should see its labour needs fall as we age. Less young people, fewer teachers needed to educate them all, right?

Index, Feb 2015=100

Index, Feb 2015=100

To be sure, education’s share of employment has grown more moderately than health care and is now 8.5%, up from 7.1% in 2000 and 7.9% in 2015. But it’s still a sector of our economy where, as Wood states, it “always has been and always will be difficult” to improve productivity.

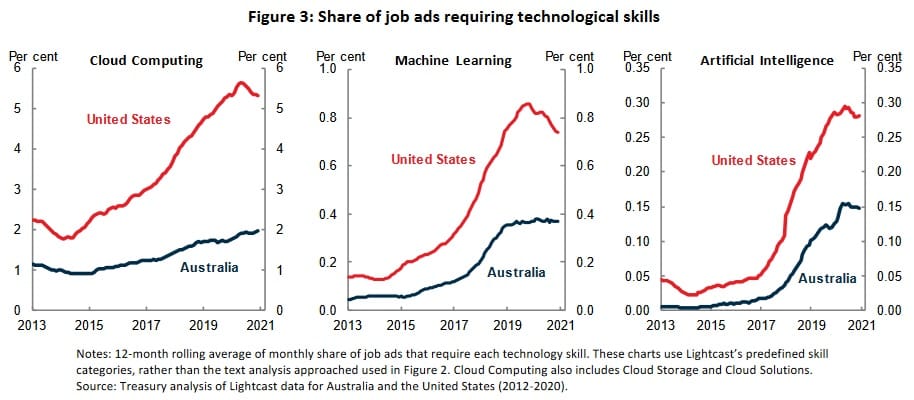

Now, more spending on education and health care is perfectly fine if – and it’s a big IF – we’re doing what Wood advised and work hard elsewhere. One way to improve productivity elsewhere is with technological diffusion, which we’ve been OK at, but nowhere near as good as the US:

But really, in Australia our “elsewhere” basically means the mining sector, which has historically accounted “for about one quarter of Australia’s measured labour productivity growth”.

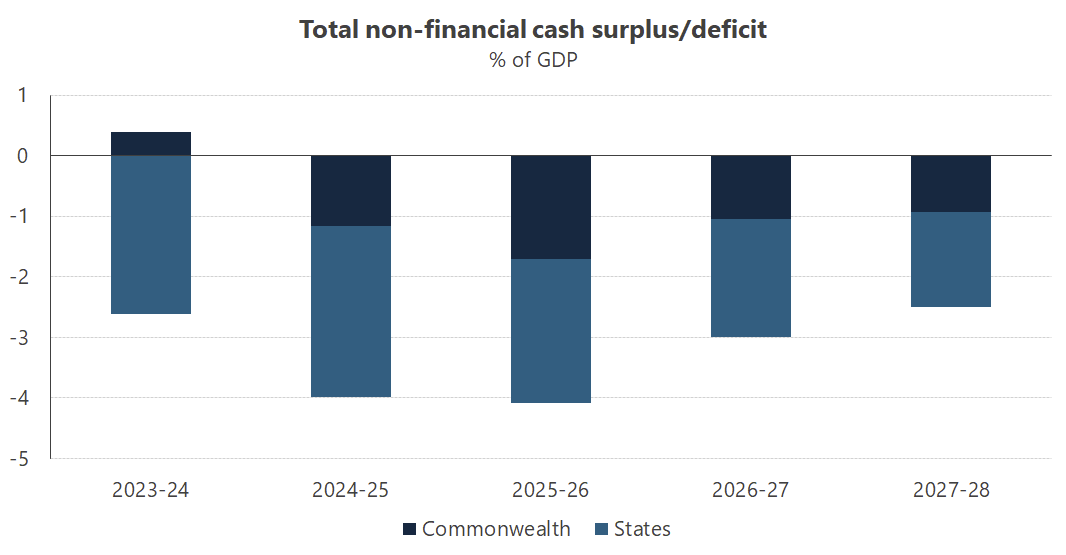

Where might mining productivity go from here? Well, the IMF reckons that commodity prices will moderate into 2025, and iron ore prices are threatening to break below $100. I think it all adds up to a much weaker labour market than is suggested by the aggregates, with the outlook highly uncertain – our state and federal governments can only continue ‘carrying’ the economy with deficit spending (much of which now goes to interest payments) for so long, right?

If I was the RBA, I wouldn’t be rushing into raising the cash rate at the next meeting.

We should be doing better

The jobs report and Wood’s comments also got me thinking: just how much has the Albanese government done to boost productivity and efficiency? If sectors like health care are consuming more work hours, we desperately need productivity elsewhere to pay for them. As Wood explained:

“If we care about these services, and we want to continue to provide these services at the kind of level that the population expects, we’re going to be having to reinvest a kind of fraction of the dividend of economic growth elsewhere into these sectors.”

Treasurer Chalmers doesn’t appear to understand that need. In an opinion piece penned in August last year, one of his “key pillars” for the economy was:

“Fourth, we are creating a more sustainable and productive care economy that delivers high quality services and supports well‑paid jobs. This is supported by our investments in health and aged care, the NDIS, early education and care, and investments in infrastructure platforms which can support more efficient and quality essential services.”

Investing more in health and education doesn’t make them sustainable unless you’re working to grow the productivity dividend elsewhere in the economy, because it’s really difficult to raise productivity in those sectors themselves.

Chalmers’ first pillar – “refreshing and renewing our economic institutions, promoting innovation and boosting competition” – addresses that, but given the employment growth in the non-market sector and contraction in the market sector, I’m not so sure the government has got the balance right.

That isn’t a criticism unique to the current government; the Scott Morrison government did virtually nothing in this space, choosing to spend its political capital on things like a link tax, maintaining JobKeeper for at least a year too long (with no clawbacks by design), and laying the groundwork for unproductive industrial policy in Australia.

But the Albanese government hasn’t done all that much to change that. Take so-called critical minerals. The Morrison government had a “vision of becoming a global critical minerals powerhouse by 2030”, which the Albanese government formalised into the Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030. Its stated objectives are to:

- create diverse, resilient and sustainable supply chains through strong and secure international partnerships.

- build sovereign capability in critical minerals processing.

- use our critical minerals to help Australia become a renewable energy superpower.

- extract more value from our resources onshore, which creates jobs and economic opportunities, including for regional and First Nations communities.

There are some huge red flags there, such as its success in part being measured by how well it “creates jobs”, rather than its actual impact. The unemployment rate has basically been below 4% for over two years now, so even the country’s most Keynesian economist would admit that ‘creating’ those jobs comes with very real opportunity costs.

What we need from this government is effectiveness and efficiency, not make-work schemes. In practice, the critical minerals strategy has been used to protect producers (and their workers) who, at current market prices, can’t make a profit. The price of nickel collapsed – which is basically the market’s way of telling us we’re mining too much! – so the Albanese government added it to the critical minerals list, giving miners “access to financing under the $4 billion Critical Minerals Facility and critical minerals–related grant programs”.

But why, exactly? We don’t use our ‘critical minerals’ to make anything of strategic importance here. We’re essentially paying mining companies (many of which have foreign shareholders) to dig up and send nickel to places like China, subsidising their manufacturing sector. It would be better for almost everyone if the resources being used to do that – e.g. the subsidies, private capital and skilled labour – were freed up for, say, housing construction. The government is on track to miss its 2029, 1.2 million homes target by a whopping 300,000, in part because of labour shortages.

I mean, if we were legitimately worried about supply chain resilience, the fleet of iron ore carriers sailing between Port Hedland and mainland China is a significantly bigger risk to our economic security than a few nickel mines. And it’s not like the nickel is going anywhere; so what if we mine that nickel in 2034 or 2044 instead of 2024? It’s still in the ground, so if prices rise in the future – reflecting its relative scarcity at that point in time – we can just dig it up then.

The hydrogen ball stops rolling

By subsidising “critical minerals”, the Albanese government is reducing productivity. The same goes for things like the recently-doubled $4 billion Hydrogen Headstart program, which is supposed to cover the “commercial gap between the cost of producing renewable hydrogen and its market price”.

That’s on top of state subsidies, such as South Australia’s $500m hydrogen jobs plan (literally called a ‘jobs’ plan… what does that tell you?), or NSW’s $3 billion to “to support industry development” in the hydrogen space.

But what if that gap never closes? It’s already quite substantial:

“According to the investment bank UBS, Fortescue’s proposed green ammonia plant at Queensland’s Gibson Island needs electricity to cost $20-$30 per megawatt hour to be viable but recent long-term contracts for large wind and solar farms are offering $70-$90 per MWh power.”

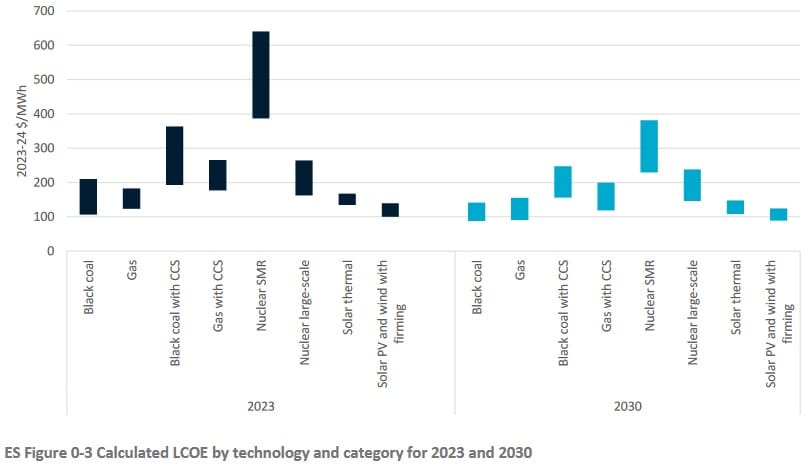

The CSIRO’s latest GenCost report puts the cheapest energy sources by 2030 at a bit under $100/MWh, which is so far above what’s needed to make green hydrogen-fuelled ammonia production (one of the best uses for hydrogen) viable that it’s hard to see it ever making sense without ongoing subsidies.

Perhaps that’s why Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest, until recently the country’s biggest proponent of green hydrogen, just pulled the plug on his plan to produce hydrogen at the site of its defunct Liddell coal-fired power station. It’s quite the change of heart for the guy who said this in May last year:

“Remember, I’m an industrialist. I’ve done this before. I see the potential in our country of an industry at least the size of Aramco, a multi-trillion-dollar company that underpins the entire economy of Saudi Arabia and that high standard of living which 34 million people have in their country.

We have the potential of creating an industry at least that size, and having economic growth for decades, full employment for decades. That is the power of this opportunity. The $2 billion gets that ball rolling.”

The $2 billion to which he referred is now $4 billion, but that still wasn’t enough. Of course there’s a number that will make it work, in the sense that with a big enough subsidy someone will be able to produce green hydrogen. But that green hydrogen comes with opportunity costs in the form of less efficiency (those dollars could have been used elsewhere) and lower productivity (supporting unprofitable ventures).

Given that a great source of efficiency and productivity is ensuring that many of our businesses are as close as they can be to the technological frontier, the electricity used to create unprofitable green hydrogen will leave less available for other, more productive uses. And new uses appear every day: the IEA thinks “electricity consumption from data centres, artificial intelligence (AI) and the cryptocurrency sector could double by 2026”, and we’re definitely going to want some of that down under (data sovereignty and all). Green hydrogen might even cause greater carbon emissions if those subsidies could have been better used in more effective places to reduce emissions, like solar or nuclear.

Let’s get competitive

I’m going to end on a somewhat positive note: there is something the government has done to improve efficiency and productivity, namely " revitalising" the National Competition Policy. The original version was part of the well-regarded reforms of the 1990s, which “contributed to the productivity surge that has underpinned 13 years of continuous economic growth”. Basically, the federal government pays the states to remove or reform a bunch of inefficiencies – taxes, duties, regulations – in their economies. Such a model is necessary because productivity-enhancing reform often causes state governments lose revenue or upsets various interest groups, while the benefits flow to everyone. It’s about fixing the incentives so that state politicians are willing to do the right thing.

But the final report isn’t due to be delivered to the government until 1 November 2024, and competition reform can take a while to work its magic, so to speak. It’s also an election year in 2025, so whether the government has the political willpower to roll out meaningful reforms that might upset the rent seekers who benefit from the current restrictions (and will therefore lobby against them) remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, the government’s industrial policy and renewables transition – even if it pays off in the long run – will lower productivity and economic growth now. Add to that the recent revelations about the actions of the CFMEU, and it’s no wonder that since 2014 labour productivity has fallen 18.1% in the construction industry, a sector that’s so ripe for reform it’s literally rotting.

If we don’t get our act together and either slow the growth in labour-intensive sectors such as health care, or start rapidly improving productivity elsewhere, we will stop growing. The term Eurosclerosis exists for a reason, and it’s not something we should be inviting with open arms down under.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!