Why I'm sour on a sugar tax

An article in the SMH did the rounds recently, with the author suggesting that the “secret” to solving obesity in Australia is a sugary drink tax:

“Breadon and his colleagues at Grattan estimate their proposed tax for Australia would reduce the amount of sugary drinks we consume by about 275 million litres a year – enough to fill 110 Olympic swimming pools.

It would mean Australians would ingest nearly three-quarters of a kilogram less sugar each year thanks to manufacturers cutting down their sugar use and consumers opting for the cheaper option: low or no sugar drinks.”

That certainly sounds impressive – lots of big numbers! – but it quickly falls apart upon closer examination.

For example, take the three-quarters of a kilogram of sugar. That’s around 2,900 calories, or a bit more than the recommended daily caloric intake for the average man. If your goal is to solve obesity, removing 8 calories a day probably isn’t going to cut it.

Then there’s the problem of elasticities, which is econo-speak for the differences in demand for a product (in this case, sugary drinks) when the price changes. A 2021 paper in the Journal of Health Economics found that while Mexico’s sugary drink tax did indeed reduce consumption, “this was compensated by increases from untaxed categories, such that total calories purchased did not change”.

So sugary drink consumption down, cholesterol, sodium, saturated fat, carbohydrates, and protein consumption up. The effect on obesity? Negligible, even if all the reduction in sugar consumption was by the obese:

“If we take the 7% reduction in soda consumption at face value, we would conclude that the tax on drinks achieved only an average reduction of 7 calories per day for adults, and less than that for children. Even if all calorie reduction was concentrated among the overweight (comprising 1/3 of the population), the reduction would amount to only about an 21 calorie (= 7 × 3) per day reduction from taxed drinks. Hill et al. (2003) estimate that to prevent weight gains calorie intake has to decrease by 100 calories per day, and Butte and Ellis (2003) say it should be at least 200 calories per day. Extrapolating linearly this would require taxes 10-20 times larger than the ones implemented in Mexico.”

Basically, if demand is inelastic then a sugary drink tax won’t do much to stop people drinking sugary drinks, so the tax will have no effect other than to raise revenue.

If demand is elastic, it will lower the consumption of sugary drinks – a minuscule part of people’s daily caloric intake – but they’ll probably just substitute to other unhealthy products instead.

Meanwhile, we’ll all have another tax on the books.

Taxes are a burden

Do sugary drinks – known as SSBs, or sugar-sweetened beverages in the academic literature – contribute to obesity? Probably. But it doesn’t automatically follow that they should be taxed. Taxes are costly, and come with what economists call deadweight losses (inefficiencies that reduce the overall economic welfare). If a SSB tax isn’t the best way to reduce the stated harms – e.g. obesity, diabetes – then it shouldn’t be imposed.

A 2018 report for New Zealand’s Ministry of Health which surveyed “forty-seven peer-reviewed studies and working papers published in the last five years” found that “the evidence that sugar taxes improve health is weak. We have yet to see any clear evidence that imposing a sugar tax would meet a comprehensive cost-benefit test”.

A paper published in the Florida Tax Review last year found that “there is little evidence that diet-targeted price interventions have had a meaningful impact on health outcomes… [because] consumers have been motivated by price interventions to eat differently, but differently isn’t necessarily better”.

Higher prices on taxed goods lead consumers “to substitute items of similar dietary value—candy or beer for soda, for example”.

That’s because unlike with other sin taxes (e.g. tobacco), sugary drink taxes are also complicated by the “vast array of alternative foods available, [so] are less predictable and more complex in their relationships to health behaviours and corollary outcomes”.

Taxes also come with unintended consequences. For example, Mexico’s sugary drink tax has even killed people due to the country’s low water quality (water is a substitute for sugary drinks), although thankfully that’s not something we have to worry about in Australia!

A sugary drink tax would be regressive

Ok, so a sugary drink tax probably won’t reduce obesity and the tax will create deadweight losses for society. But what about the disadvantaged, who spend more of their incomes on sugar? According to the author of the SMH article, a tax would help them, and raise money for the government to presumably do other good things with:

“Disadvantaged Australians, who are the hardest hit by obesity, would be the biggest winners, Breadon says. And the financial drain on households and the wider industry, including sugar farmers, would be fairly small given about 85 per cent of Australia’s raw sugar is exported.

While the main goal of a sugary drinks tax would be to improve our health, it would also benefit the government’s bottom line (which has suffered in recent years as tax revenue from tobacco has plummeted). If introduced today, Grattan estimates, the sugary drinks tax would raise nearly $500 million in the first year, while also generating savings by reducing the demand for healthcare.”

Again, sounds good. Except that they’ve only counted two benefits – health and tax revenue – and ignored everything else. For example, the “disadvantaged” probably get some enjoyment out of drinking sugary drinks. They probably also get some enjoyment out of not being taxed for the pleasure.

Contra the SMH article, a paper by the New Zealand Treasury found, “a sugar tax would be regressive at the general population level”.

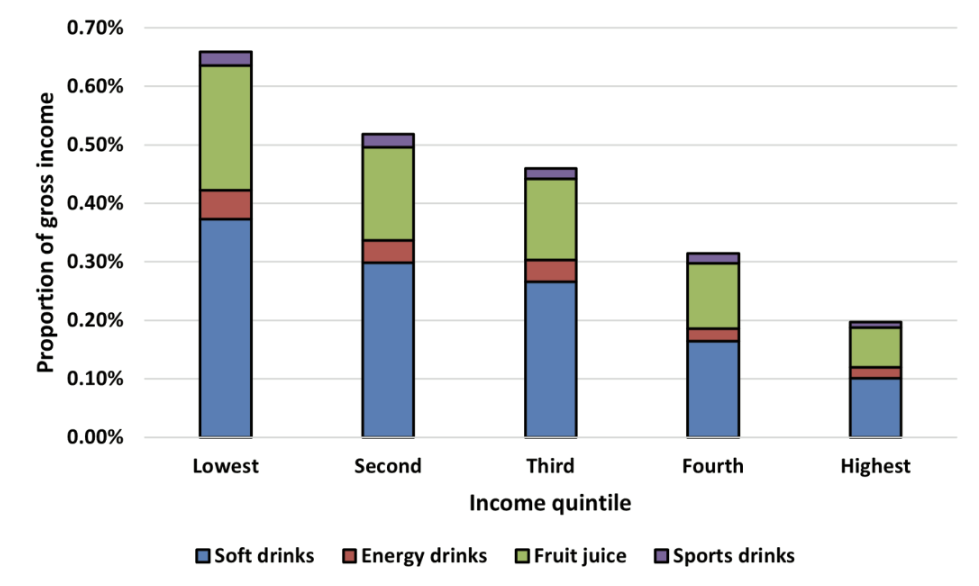

Why is that? Because poorer households spend more of their income on sugary drinks, as was confirmed by a PBO analysis commissioned by Labor MP Mike Freelander in 2024:

Most of a hypothetical 20% tax on sugary drinks, which the PBO expects could raise around $700 million a year, would be paid by households with the lowest incomes – precisely the “disadvantaged” the author purports to help with this tax.

Obesity is a complex problem

A sugary drink tax will not do anything to reduce obesity. But it is politically popular, because politicians can stand proudly aloft their moral high horse, claim to be doing something about public health, while raising a cheeky sum of revenue in the process.

That the tax will achieve none of its stated goals other than raising revenue from those who can least afford it doesn’t matter; it will represent a minuscule share of people’s budgets and, once passed, they will soon forget it even exists. Meanwhile, the public health crusaders will shift their focus to the next vice enjoyed by the unwashed masses.

But that doesn’t mean nothing can be done to help reduce obesity. Plenty of research has shown that early detection, providing helpful knowledge at schools and to parents, and ensuring the proper nutrition during pregnancy can be effective anti-obesity policies.

If a more proactive approach was desired, a tax could still work. A 2020 paper published in Health Economics compared various solutions to obesity, including “a fat tax (levied on food-away-from-home), a thin subsidy (levied on groceries that enter home food preparation) and a sales tax on all food items”.

It found that a food sales tax outperformed the more targeted measures – including taxes on sugary drinks, which are “ineffective or even counterproductive in reducing obesity” – because it:

“[M]ay stimulate time-intensive healthy consumption by lowering the opportunity cost of time spent on food preparation. Therefore, it may exert a positive effect on the demand for healthy meals… A calibration of the model shows that the sales tax mitigates obesity at the lowest welfare cost for consumer. Furthermore, the deadweight cost of the sales tax is small in absolute value. It imposes an excess burden of less than 2 cents per dollar of tax revenues and 3 cents per 100 kcal reduction in the calorie-intake.”

Note it’s a modelling paper, so suffers from the same flaws as all of the other studies that look at this issue: a lack of observations of real behaviour.

Now, Australia already has a sales tax – the GST. But certain food items are exempt, which is the equivalent to the 10% healthy food subsidy in the paper. While that probably increases the number of meals cooked at home, it won’t reduce the number of unhealthy meals very much, so “is counterproductive and increases weight slightly” compared to a tax on all food.

So, the GST exemption for food could be removed, making it a more optimal tax for reducing obesity (the higher costs and time-intensiveness of production will reduce the overall number of dishes prepared).

But good luck raising food prices during a cost of living crisis!

A more palatable option might be to target obesity itself, such as by awarding “tax credits to obese people who lose weight. A tax directly pegged to reduced obesity would certainly be a much more efficient way to achieve the stated policy goal of reducing obesity.”

Another solution for reducing obesity may be technological. Drugs like Ozempic (semaglutide) have helped obese people achieve “sustained, clinically relevant reduction in body weight”, with a notable down-tick in US obesity being labelled as the end of “peak obesity”. It might even help other people lose weight through “social contagion”.

Ozempic hasn’t taken off in Australia because it’s only approved “for lowering blood sugar in adults with type 2 diabetes”. I don’t know enough about it to weigh in one way or another, but if obesity were truly so concerning to justify an ineffective sugary drink tax, then perhaps policymakers could “nudge” the TGA into an investigation?

Basically, obesity is a complex problem that needs to be tackled from several angles and there are no easy answers. But I can unequivocally say that a sugary drink tax is not the “secret to better health and less obesity”.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!