Why we may not be done with inflation

Last week Canada became the first major economy to cut interest rates since the pandemic, followed closely by European Central Bank (ECB) a day later. Those decisions raise the obvious question of: when is it Australia’s turn for a rate cut?

But before diving into that, let’s take a quick look at why these central banks decided to cut rates. First up was the Bank of Canada (BOC):

“In Canada, economic growth resumed in the first quarter of 2024 after stalling in the second half of last year. At 1.7%, first-quarter GDP growth was slower than forecast in the MPR. Weaker inventory investment dampened activity. Consumption growth was solid at about 3%, and business investment and housing activity also increased. Labour market data show businesses continue to hire, although employment has been growing at a slower pace than the working-age population. Wage pressures remain but look to be moderating gradually. Overall, recent data suggest the economy is still operating in excess supply.

CPI inflation eased further in April, to 2.7%. The Bank’s preferred measures of core inflation also slowed and three-month measures suggest continued downward momentum. Indicators of the breadth of price increases across components of the CPI have moved down further and are near their historical average. However, shelter price inflation remains high.”

Ok, so growth is slowing in Canada despite “solid” consumption and investment, but most importantly the BOC thinks the economy is “operating in excess supply” – that’s econ-speak for market prices being above what it deems competitive prices. Add that to inflation slowing to within its 1-3% target band, with “continued downward momentum” expected, and it’s not hard to see why the BOC started to ease.

Now here was what the ECB had to say (curiously, there was some dissent in this decision):

“Since the Governing Council meeting in September 2023, inflation has fallen by more than 2.5 percentage points and the inflation outlook has improved markedly. Underlying inflation has also eased, reinforcing the signs that price pressures have weakened, and inflation expectations have declined at all horizons.”

What’s interesting is that unlike Canada, inflation in the eurozone accelerated in May, rising to 2.6% from 2.4% in April. Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, rose by the same 0.2 percentage points, and nominal wages have been growing above expectations this year. So while this might be the first of several cuts for Canada, the ECB may now be on hold:

“At the same time, despite the progress over recent quarters, domestic price pressures remain strong as wage growth is elevated, and inflation is likely to stay above target well into next year.”

So, what does all this mean for Australia? Let’s just say that our economic situation is vastly different and we should be careful reading too much into these decisions.

Why we’re different

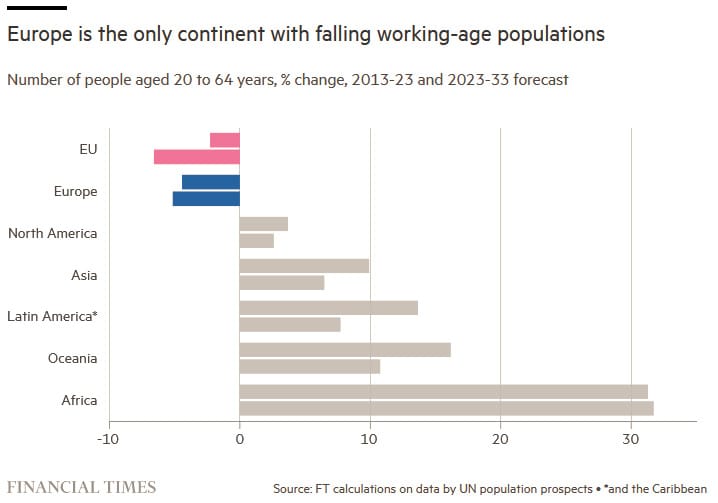

I’ll start with the eurozone, which is on the only continent in the world where the working-aged population is falling:

When a country or region’s demographics worsen, it tends to reduce R*, or the natural rate of interest. Think of that as the rate that would prevail “if economic growth and inflation were balanced”.

An older population will, all else equal, lower the intertemporal rate of substitution in an economy (older people generally prefer to consume more today than in the future), reducing savings and investment, lowering potential growth rates and the natural rate of interest. A lower R* then means a central bank’s interest rates should be lower. So while the ECB’s key cash rate is now just 3.75% and Australia’s is 4.35%, the former’s may actually represent tighter monetary policy, given the differences in potential growth.

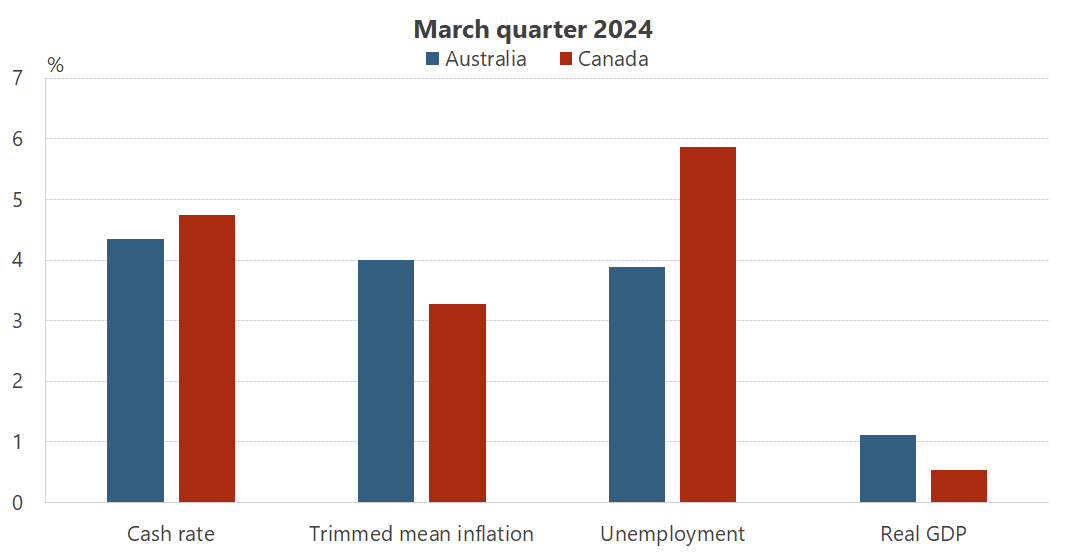

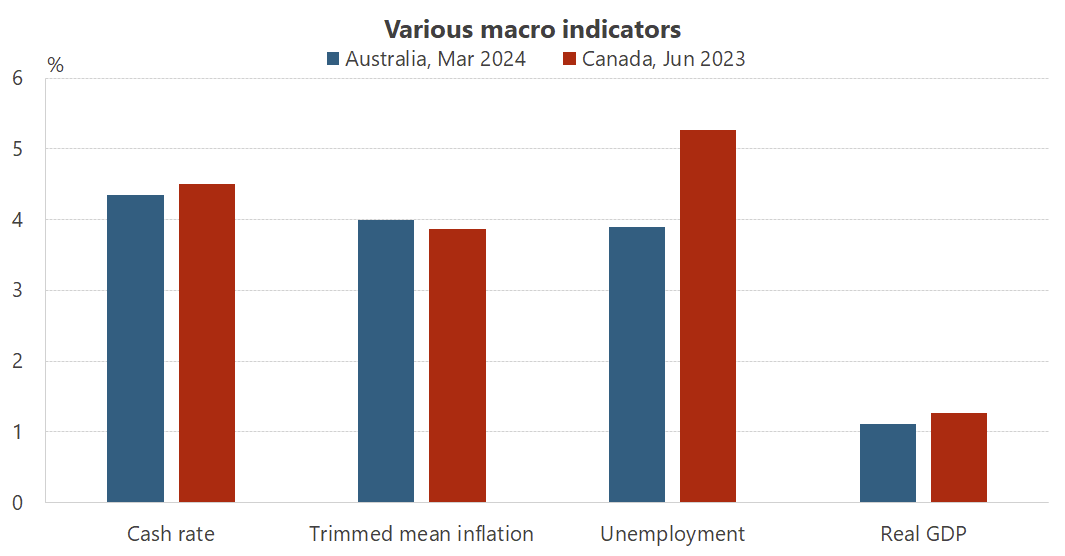

Then there’s Canada, an economy that has much more in common with Australia. But even Canada has key differences that are important for monetary policy decisions. They say a picture is worth a thousand words, so here’s a chart showing just where each country stands (all March quarter except Canada’s recently cut cash rate, which is June):

Economic growth in Australia is weak, but not as weak as in Canada, which also has higher unemployment, lower inflation, and a cash rate target above Australia’s. In fact, Australia today is roughly where Canada was a few quarters ago:

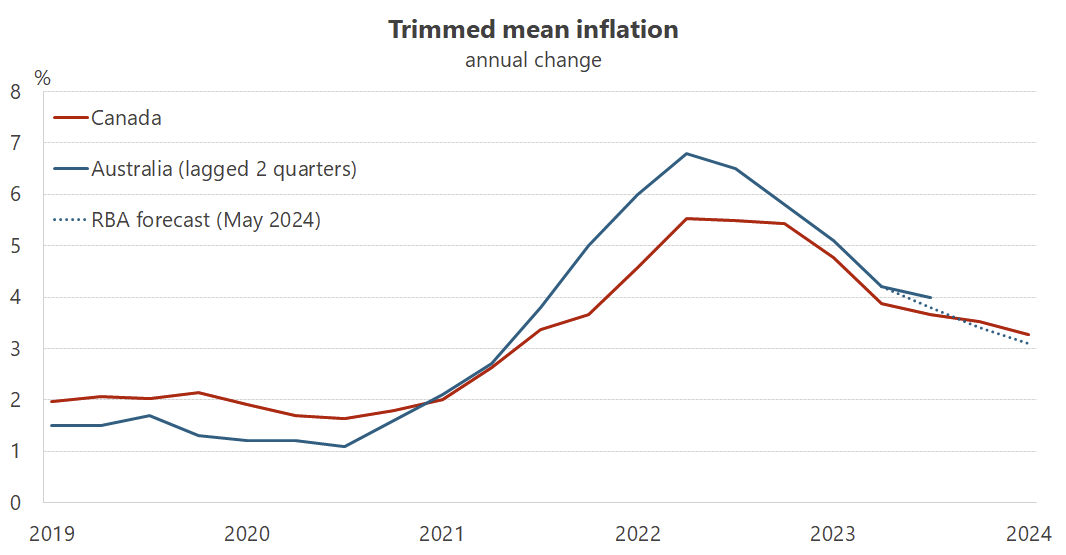

There’s obviously a lot going on in both countries, so we can’t simply conclude that we’re now about 9 months away from a rate cut based solely on a comparison with Canada. But as I wrote back in January, “Australia and Canada broadly tracked each other until July 2021, when Canada’s CPI shot up but Australia’s collapsed. The reason? Over half of Australia was suddenly locked down”.

That’s still true: Australia and Canada’s inflation trajectories still track each other quite nicely once Australia’s data are lagged by 6 months:

Last week Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) deputy governor Andrew Hauser basically said that if Australia was in Canada’s position, the decision to cut rates would be “fairly straightforward”:

“Their interest rates were higher than ours. Their inflation rate is lower than ours, and their unemployment rate has picked up quite a bit more substantially than ours.

“I think if you took those data out of Canada and you plugged them into the Australian context, you might well see a different policy stance.”

But plenty can happen in the next six months and as Hauser stated, the RBA has been more dovish than its Canadian counterpart, so it could even take longer here.

Walking the narrow path

One reason the RBA is more dovish than the BOC is because the RBA, as part of an agreement with Treasurer Jim Chalmers late last year, explicitly stated that it’s prioritising the full employment mandate over a quick return to price stability:

“The Board is attempting to bring inflation down while preserving as many of the recent gains in the labour market as possible – what my predecessor called ’the narrow path’.”

The BOC has no such constraint; its mandate recognises that employment is “determined largely by non-monetary factors that can change through time”, and so “the primary objective of monetary policy is to maintain low, stable inflation over time”.

Having employment weighted equally to stable inflation can be dangerous, because it may lead the RBA to go easy on inflation in a futile attempt to prevent higher unemployment, even when it’s caused by non-monetary factors. And if the RBA fails to adequately control inflation, its credibility could be damaged, which Harvard professor and former Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund Ken Rogoff warned is an invitation for politicians to get even more involved:

“When faced with economic uncertainties, central banks may not aim for high inflation, but they will likely adjust their interest rate policies in a way that makes such an outcome more likely than a deep recession or a financial crisis.

…

Central bankers understand that as soon as markets doubt their intentions, interest rates will quickly reflect rising inflation expectations. Nevertheless, this realisation is unlikely to help them resist pressures from politicians, who often focus only on the next election and may prioritise other issues over stabilising short-term inflation.”

While it’s a noble goal to preserve full employment, persistent inflation and a more politicised RBA will cause significantly more damage to the economy in the long-run than slightly higher short-term unemployment. Alas, it’s too late to change tack now without losing even more credibility (or copping flack from Chalmers); the RBA has made its bed and I sincerely hope it’s right. But while it’s waiting on the sidelines, other forces might be quietly undermining its plans.

What could prevent rate cuts

You might think that Australia’s very weak real GDP growth means there’s a chance the RBA follows Canada and cuts rates soon. But it’s possible to have a weak economy and persistent inflation, also known as stagflation, especially when household consumption is robust, which it is: it grew at an annualised rate of 4.9% in the March quarter.

Additionally, most of the inflation we still have today is in non-tradables, i.e. domestic factors; things like your haircut or morning coffee. One way for that inflation to become persistent is if real wages rise above labour productivity, as documented by the Productivity Commission (PC) last year:

“In the 1960s and 1970s, wage growth tended to exceed labour productivity growth (a ‘real wage overhang’), which was seen as one precipitating factor for the high inflation and unemployment rates of that period. Various reforms and other structural changes in the 1980s and 1990s more closely aligned wage growth wages with productivity growth by the end of the mid-1990s.”

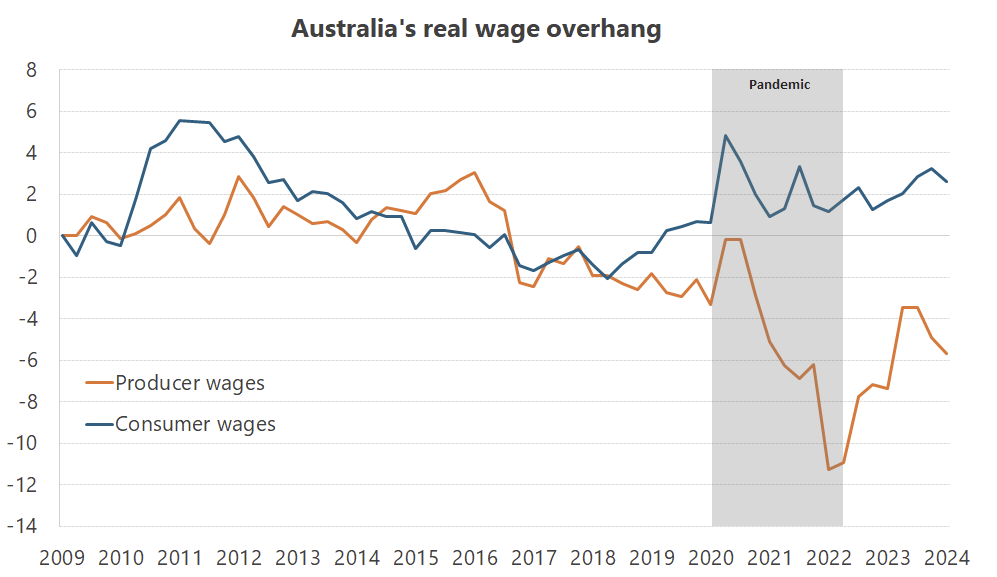

The pandemic really shook up the labour market, creating a significant wage decoupling between consumer wages (a proxy for what workers can buy with their income) and producer wages (a proxy for what it costs businesses to hire workers). Here’s a chart showing both relative to labour productivity:

Over the long run, both lines tend to converge around zero. That’s clearly not the case today, likely due to the pandemic-induced mining boom. Here’s the PC again:

“Rising commodity prices depress real producer wages, driving a wedge between them and real consumer wages… As a rising terms of trade depresses real producer wages, but has little direct effect on productivity (which measures output per unit of input), the rising terms of trade also drives a wedge between productivity and producer wages.”

For wages, the blue line is more important: as that approaches zero, workers will demand higher wages. But because businesses can’t pay people consumer prices, the orange line is more important for employment. The fact that the orange line (producer wages) is so far below labour productivity probably goes some way to explaining our presently strong job numbers, while the positive blue line (consumer wages) might explain our strong rates of participation.

However, the PC also cautioned that the figure can be misleading because it includes mining and agriculture, two sectors with relatively few workers but that “drive the aggregate results”; it’s likely that the gap is much smaller than the one shown in the chart.

On a knife’s edge

I agree with Treasurer Chalmers when he says:

“Strong and sustainable wage growth is part of the solution to cost of living pressures, not part of the problem.”

The key word there is sustainable. Last Monday, the Fair Work Commission (FWC) increased the minimum wage by 3.75%, a rate higher than the current rate of inflation and well above of the RBA’s 2-3% inflation target. Around one in four Australian wage contracts are linked to the FWC’s decisions, so if the real wage overhang is closer to zero than suggested by the data – as is almost certainly the case, given our insipid economic growth and the impact of mining on the aggregates – it may start to cause disemployment effects in industries such as hospitality, where wages can be nearly half of total expenses.

If so, the economy will slow even further, yet the RBA may be unable to ease monetary policy because wage inflation keeps price inflation elevated. It’s a tricky situation, no doubt, and the FWC at least appears aware of the trade-offs:

“[W]e consider that it is not appropriate at this time to increase award wages by any amount significantly above the inflation rate, principally because labour productivity is no higher than it was four years ago and productivity growth has only recently returned to positive territory.”

That’s good, but paying lip service to productivity is not enough; as the 1960s and 1970s showed, when the wage setting process becomes linked to inflation rather than productivity, a wage-price spiral is very much still a possibility. And there are already signs that some of our states are violating that principle when negotiating wages, such as the Queensland’s government’s agreement with its power companies to “to review Brisbane CPI movements over the term of the deal and increase base rates where inflation exceeded wages growth”, resulting in a new deal this year that “could drive up costs for the power companies by more than 30%”.

No one wants real wages to fall. But for real wage increases to be sustainable, they must not get too far ahead of productivity; linking nominal wages to inflation rather than productivity is a good way to create unemployment and inflation.

The next several months are going to be telling. Wages are increasing faster than inflation, despite modest labour productivity improvements. On 1 July, our federal government will inject more than 1.5% worth of GDP in tax cuts and new spending. The RBA seems to have a bias towards its employment mandate, and consumer inflation expectations a year from now remain anchored above 4%.

I hope the RBA has gets this one right but I also worry that our governments, by running large fiscal deficits and influencing various wage setting processes, might have thrown a curve ball that it has completely misread. If so, the only way we’re getting rate cuts this year is if we end up in a full-blown recession.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!