A public property developer won't fix housing

The Greens released their much-hyped housing plan last week and while I wouldn't normally give this much attention to a minor party's policy, it was just so full of well-meaning but really confused policy, I just had to weigh in.

Before getting into it, I should make it clear that the Greens' existing housing plan is much broader than what was announced by Greens spokesperson for Housing and Homelessness, Max Chandler-Mather. For example, it includes rent freezes and long-term rent caps, both of which are much more economically destructive than anything that was proposed last week.

But on to the policy. The Greens, should they attain sufficient electoral power at the next election, want to:

- Establish a public property developer within a new Federal Department of Sustainable Cities, Development and Housing to build 360,000 homes over 5 years (610,000 over 10 years) and sell/rent them at below-market prices.

- Focus on sustainable, medium-density developments integrated with public transport and amenities that incorporate design principles like rooftop gardens, high energy efficiency, and minimal parking.

- 30% of homes would be made available for purchase at 5% over the cost of procurement, with the remaining 70% rented out, with priority given to those with 'local connections', and 20% of those rentals would be reserved for the bottom 20% of income earners.

- Scrap tax deductions for private property investors, on which the government "spent $27 billion... this year alone".

- Estimated underlying net cost of $27.9 billion over a decade, with a headline cost of $285 billion (which includes off-balance sheet "investments" such as land costs, interest costs on debt and rental and sales income).

- The average renter would save $5,200 per year (19% discount), average home buyer would save $260,000 (33% discount).

Where's the market failure

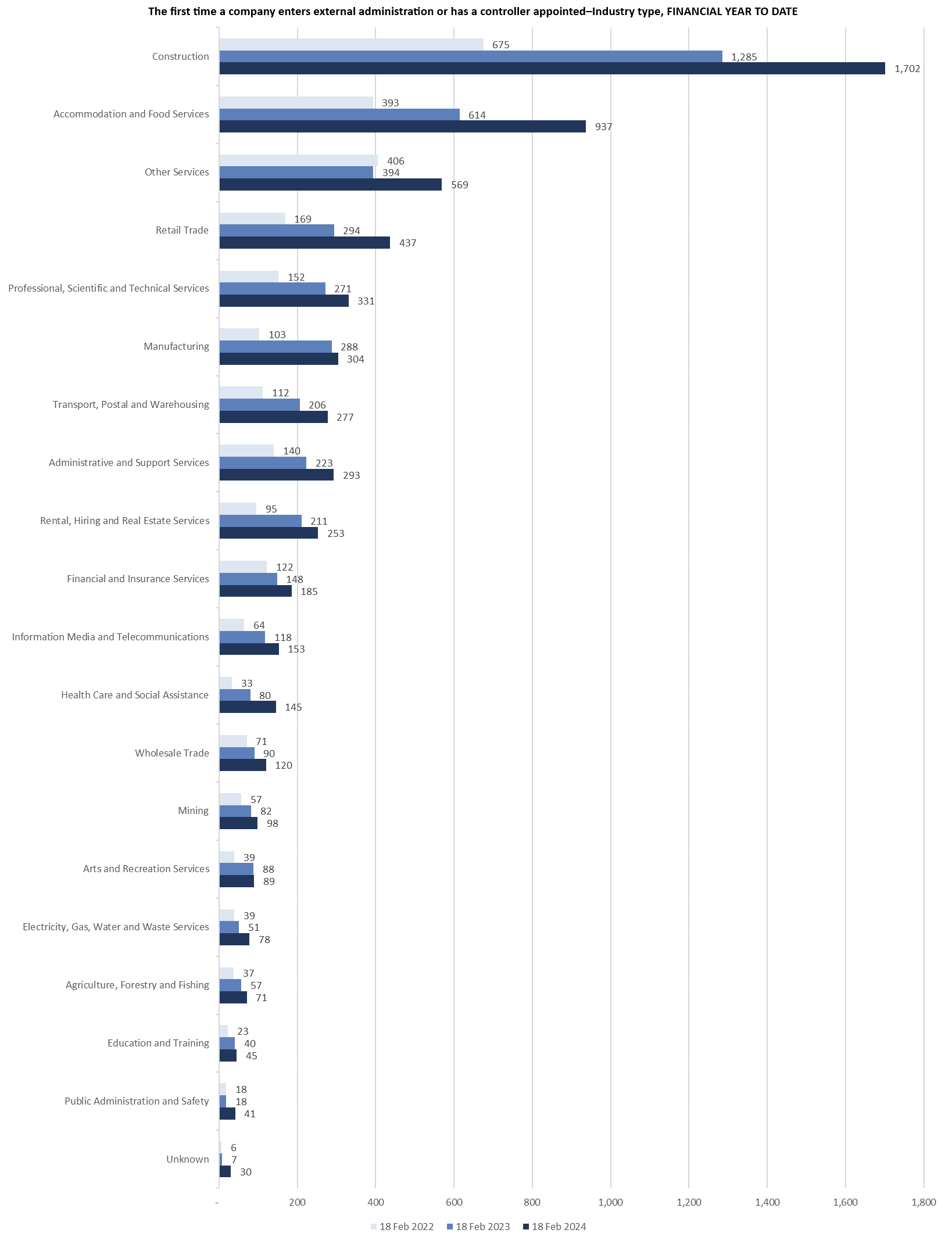

The fundamental problem with the Greens' proposal to create a public property developer inside a new government department is that there's simply no need for one. Chander-Mather's claims that there is a "monopoly" of private developers that needs government competition to "break" it is just flat out incorrect: we have no shortage of private property developers in Australia; in fact, it's an incredibly competitive sector with razor-thin margins and a high failure rate – nearly double the next highest industry.

These profit-hungry developers don't need an incentive to construct enough homes for every Australian at competitive prices; they just need permission. It's not clear how a federal government department will be able to jump over the numerous local hurdles that currently obstruct private developers. And whatever the new department is successful at building will crowd-out private investment: all of its housing will be sold/rented at below-market prices (i.e., at a loss), making it difficult or impossible to compete against it and raising significant competitive neutrality issues.

Moreover, the new public developer will compete for scarce resources, driving up the prices for construction materials and the skilled labour needed to build homes. This is especially problematic in an economy with close to record-low rates of unemployment.

All of those unintended consequences may well be a desirable outcome for the Greens, given their aversion to profits – especially "profit hungry developers" – but it's not good policy and will make most people worse off.

Location, location

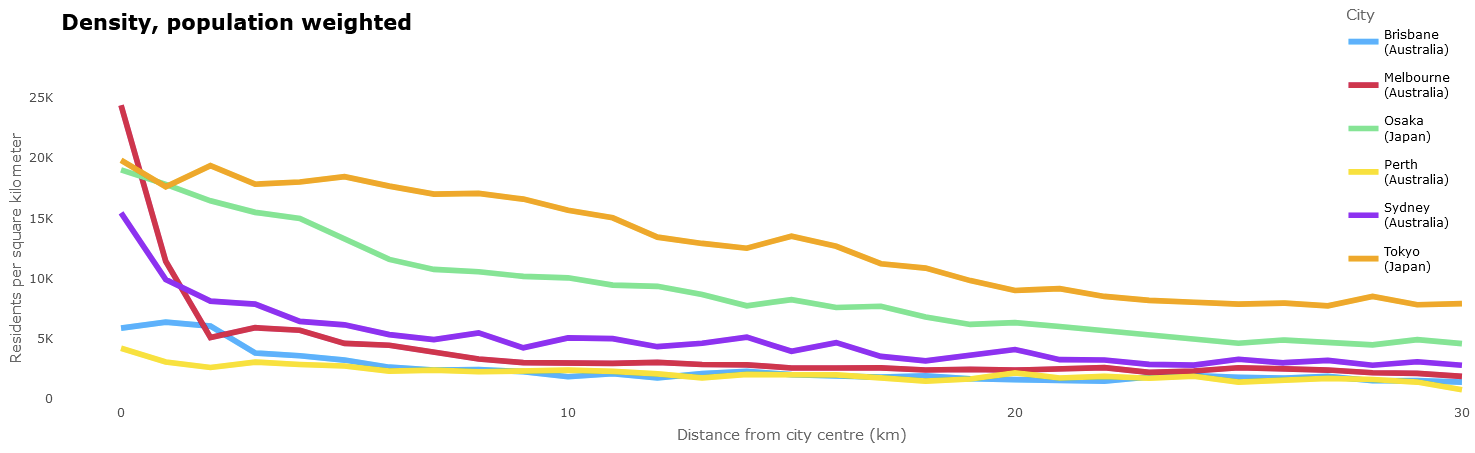

There's nothing inherently wrong with the Greens' plan to construct medium-density developments located close to public transport and amenities; in fact, it's a great way for a city to increase its average density. Australia needs to do a lot more of that, and not just near the CBD. One reason big but still very liveable cities such as Tokyo and Osaka do quite well is because they allow density to gradually decline as you move out from the centre, rather than the all-or-nothing approach that is used in most Australian cities.

The issue isn't that private developers don't know that; it's that they're not allowed to increase density beyond designated 'corridors'. It's why we have a 'missing middle' in Australia, with density in our cities (inner Melbourne is denser than inner Tokyo) surrounded by an ocean of single family detached dwellings.

As the NSW Productivity Commission pointed out, we need more housing of all types:

"An efficient market should provide a mix of housing forms to reflect the preferences of the community. Different property types will have different prices to reflect the market’s assessment of their amenity.

There are areas where high-rise apartments should be immediately prioritised—for instance, beside new transport hubs. But some scope remains for allowing medium-density housing. There may be sites that suit specific developers (including existing owners), as we see with ‘granny flat’ and dual-occupancy development in Sydney. Greenfield developments are also incorporating denser dwellings (whether smaller detached lots or multi-unit dwellings).

A greater focus on higher-density where there is greatest unmet demand for housing could also increase the viability of medium density by lowering land values in other parts of the city."

The Greens plan does nothing to resolve this issue, largely because it can't: land use zoning is a local, state and territory issue in Australia. We can't even build public housing. To fix that requires "improvements to planning, zoning and land release systems", which federal Labor's Housing Accord addressed, but only indirectly.

While it might be tempting to the naive politician, attempting to transplant something that works elsewhere (I know that Chandler-Mather is a big fan of Vienna), without considering the unique history, political environment, and financial and legal regimes of each place – i.e., its cultures, norms and institutions – is a recipe for disaster.

Failing to consider the incentives

The final pillar of the Greens' housing plan, which makes 30% of the homes it constructs available for purchase at just 5% above cost, with the remaining rented out with various conditions, has several problems.

First, it's inequitable. Priority will be given to those who have "connection to the local area, including if they have children enrolled in local schools, work and support services connections, or if they are First Nations peoples".

Sounds great, but the people already renting in the desirable areas Chandler-Mather wants to build these below-market rate houses are probably young, relatively high-income earners: people like himself. It's not clear that the rest of us – including much less well off, middle-aged people living in the suburbs – should be subsidising people who in all probability will earn more lifetime income than themselves.

Incidentally, this is also an issue in Vienna, where housing policy favours the established middle class over "the really poor and needy", and is less "newcomer-friendly" than Australia's rental housing market. We're a nation of immigrants, not a relatively homogeneous city with a total population of around 2 million, so that's a kind of a big deal.

Second, the rent cap on "25% of your income or market rent, whichever is lower" will see the government lose a considerable sum on these rentals. If you earned the national average household income, which is currently around $120,000, your rent would be capped at $575/week, or around 70% of the market rate for a 2-bedroom unit in hipster-paradise Newtown, Sydney. It will also create the potential for unintended consequences: evidence from rent control in other cities suggests that it "limits renters' mobility by 20 percent", which has benefits (enables them to stay) but also costs (unable to move as their needs change, such marriage, having a child, or career opportunities).

Third, the plan fails to consider the full costs of home ownership. The lucky few who manage to buy a house at a 33% discount to market rates will be confronted by costs down the road, and it's not clear who will pay for them. Why would someone undertake important maintenance on a house that can only be sold back to the government at the purchase price plus inflation? What if a value-adding renovation is needed when someone's living requirements change? In such scenarios, owners may be forced to move – and presumably pay stamp duty and other transfer fees all over again – given their asset would not reflect any of that value add.

The policy also neglects to mention mortgage costs, which on a $500k loan at an average of 6% would mean total payments of nearly $1m (principal and interest) over 25 years. Will the Greens' plan be limited to cash buyers?

By not considering these incentives, the people who buy these houses may well end up being those who intend to 'wear them hard'. Do zero maintenance, depreciate the house as much as possible – perhaps even sublet a room or two – then flog it back to the government at the original purchase price in a condition far worse than that.

Understanding their motives

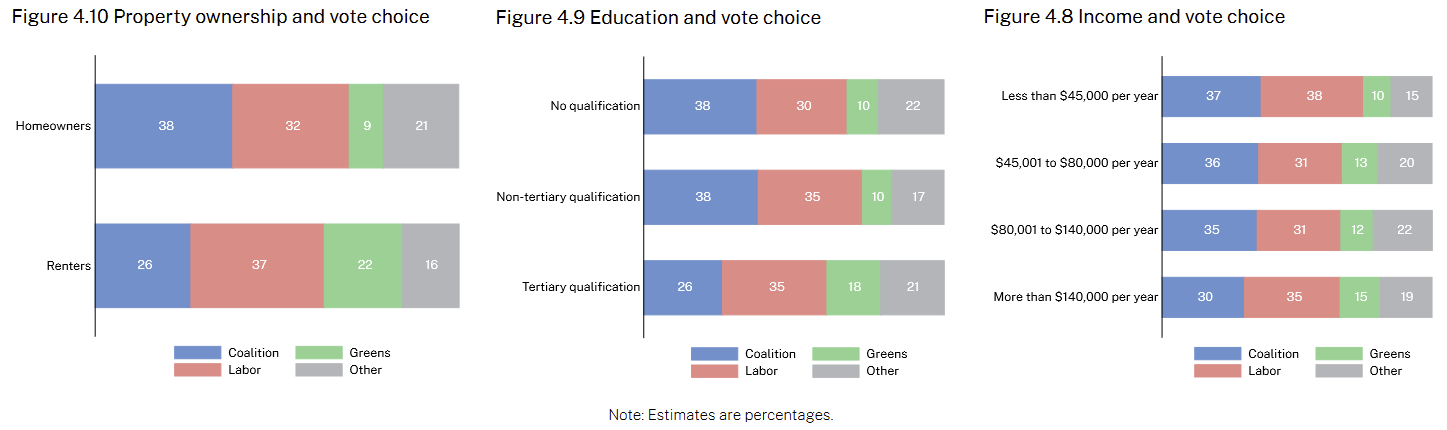

You don't produce policy like this by mistake; there's political motivation here. And to understand why the Greens have produced this plan, we need to look at the people who vote, or are likely to vote, for the Greens at the next election.

Politically, the Greens aren't trying to swing Liberal voters to their side; their targets are young inner-city Labor and Teal voters, who might be persuaded to move further to the left with "bold" housing policy such as this. It's why Chandler-Mather's attacks haven't been aimed at Peter Dutton but on Anthony Albanese, criticising his large property portfolio and the fact he purchased his first home in Marrickville for $146,000 in 1990, which could cost $2m today.

University-educated Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and the Gen Z (1996+) of voting age form the bulk of the Greens' base. Given their age, they are more likely to rent than any other demographic, but also have relatively high incomes consistent with their educational status.

If you were seeking policy that caters to a young, well-educated but politically inexperienced demographic that currently rents close to their well-paid job in the city, the Greens' policy is music to your ears: why not have the rest of Australia pick up some of your rental tab, or subsidise your path to home ownership? By concentrating subsidies on a key young, urban demographic base, the Greens are looking to solidify support from this voting bloc, despite the broader economic costs.

Such a strategy is basic political economy: voters pay attention to current economic conditions, and will often vote for policies that improve their situation even if it comes at the expense of future economic conditions. Moreover, by concentrating the benefits on a relatively small cohort – young, well-educated, well-paid city dwellers who rent – but dispersing the costs across everyone, the Greens' housing policy can still 'win' in a democratic society even if the total benefits are below the costs.

According to the 2022 Australian Election Study, the Greens have been executing that plan exceedingly well:

"The assumption that Millennials will shift to the right as they age has thus far not been borne out by the evidence, with generational effects much more significant than life cycle effects in understanding voter behaviour in Australia. The implication is that through processes of generational replacement, the electorate is moving to the left and becoming more progressive in a range of policy areas. The 2022 election saw one impact of this generational shift with the success of the Greens in four of the nation's youngest electorates, increasing the Greens' representation from one to four seats in the House of Representatives."

Housing is very important to young people, and the perception amongst many Millennials and Gen Z is that it's increasingly out of reach. Making housing affordable by fixing planning and zoning laws is a relatively bipartisan issue, so if the major parties want to claw back some of the Greens' gains then they need to start addressing young people's concerns, such as by embracing YIMBY-ism (Yes In My Back Yard).

Let them build

I don't want to be too harsh on Chandler-Mather; I believe he means well, and misunderstanding what makes housing less affordable, including blaming developers rather than NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard) for high prices, is common among the general population:

"We asked respondents to designate up to three actors (from a list of eleven) as 'responsible for high housing prices and rents in your area'... we observe a very strong tendency to blame housing providers (developers) for high housing prices. Conversely, actors whose stock in trade is opposing new development (environmentalists, anti-development activists) are almost never blamed.

...

All of this coheres with the notion that the mass public sees high housing prices and rents as caused by putative bad actors' malevolence, rather than development restrictions and impersonal market forces."

Higher density and new developments, at least in the short run, will make things worse for existing residents – including renters. Those residents also see developers in the news becoming billionaires, donating to political campaigns, bypassing their local representatives, or bribing officials outright to get projects approved. Perhaps that leads them to conclude that development, and developers, are bad overall, even though they're the group most responsible for lowering prices.

But regardless of how people feel, it doesn't change the economics. The best way to improve housing affordability with housing supply, and the best way to do that is to let people build and communicate why it's important. Yes, some developers will make money. But what they make will be considerably less than what the alternatives, such as doing nothing or adopting something like the Greens' proposal, will cost us all in the long run.

Rather than distorting markets through a centralised public developer funded by taxpayers, we should look for reforms that enable more housing at all density levels, which is crucial for improving long-term affordability.