How to lose a truck load of cash

There's doing your job to the best of your ability amidst great uncertainty, and then there's risking it all because everyone else was already doing it.

Unfortunately for Australia, when push came to shove in late 2020, former Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) governor Philip Lowe appears to have done the latter. At least that's my interpretation of a recent Freedom of Information (FOI) request, which was fulfilled on Monday at my request.

How the mistake was made

In early November 2020, the RBA embarked on what's known as quantitative easing (or 'QE' for short), which is the fancy term for when central banks buy government bonds to increase the money supply or lower long-term interest rates. It's especially popular when the cash rate is already at the so-called 'zero lower bound', i.e. when the cash rate is at or near zero, but the central bank wants to ease monetary conditions even further. As Lowe said at the time:

"The lower interest rates and our plan to buy $100 billion of government bonds over the next six months will help people get jobs and support the recovery of the Australian economy."

My FOI request sought all documents from 1 July and 3 November 2020 about the costs, benefits, or risks of the RBA buying government bonds. In other words, I was after the evidence that Lowe had on-hand when he and the Board made their decision.

The trail of emails began in August 2020 after several other countries, including England, the US, EU, Canada and New Zealand, had already been running their own bond buying programs for a few months. The RBA was late to the QE party because it had initially opted for a more limited yield target program, which as we all know eventually collapsed in spectacular fashion (by central bank standards), causing "bond market volatility and some dislocation in the market... [and] some reputational damage to the Bank".

But back to the emails, which started after Lowe asked an analyst what they thought about "a flatter AUD curve", and "our ability to achieve it". After some internal back and forth that saw one analyst warn about the potential to lose a "truck load of cash", the final email to Lowe stated that they were "sceptical about how helpful it would be... and there is a lot uncertainty about the potential outcomes".

The following are all direct quotes from the final email sent to Lowe but the points have been trimmed – do read the PDF for the full context:

We could flatten the curve at a relatively low cost

- Bond purchases would increase the size of our balance sheet substantially, exposing us to losses (if we are successful in stimulating demand and inflation).

- Market functioning might be impaired if we end up holding a large share of government debt.

- Bank profitability could be diminished a little.

But the benefits also seem low, particularly while tight COVID restrictions remain in place

- Some depreciation of the exchange rate.

- Some portfolio rebalancing.

- Little to no impact on government financing.

- Little to no impact on borrowing rates.

The real kicker was at the end of the email, when the analysts suggested that "a quantity target may be preferable to a yield target", because they were rightly worried about the RBA "defending a long‐end yield target [which] may require very large bond purchases, to counteract changes in global conditions".

As we all now know, rather than replace its yield target with QE as alluded to by these analysts, the RBA board decided to engage in both until the yield target imploded in 2021 exactly as the analysts warned it might.

The formal analysis was toned down

The FOI also included three short internal reports titled The effect of QE: Theory and evidence, The effect of QE: Possible size and length of a QE program, and The effect of lower interest rates along the curve, dated 21 September, 1 October and 12 October 2020, respectively. I assume that these reports made it all the way to the top brass of the RBA, but they may not have.

Alas, the reports say very little about the costs, benefits or risks of QE in Australia. I suspect that means that sometime in September, the RBA's board had already decided it wanted to do QE and only wanted to know how much and for how long. Curiously, a section that looked at the response to QE in other countries found "the change in yield seen is not closely related to the size of the [balance sheet] expansion", yet the RBA still went ahead with its own version along with this commentary:

"This quantity target is similar to the approach adopted by many other central banks, which have responded to the pandemic with government bond buying programs. The evidence is that these programs have lowered government bond yields in other countries."

That's certainly an interesting (i.e., wrong) interpretation of the evidence that it was provided by its analysts! The RBA just didn't want to miss out on all the fun other central bankers were having with their new tool.

Based on the evidence, the RBA's board looks as though it was flying relatively blind. It had some idea of what a $100 billion QE might do to the exchange rate, asset prices, bank profits, and yields. It knew there might be "modest" benefits. But it did not even come close to undertaking a cost benefit analysis before engaging in one of the most extreme and costly examples of discretionary monetary policy Australia has seen in the post-float era. Across the three reports, the only warning about possible costs was provided as a single paragraph:

"A QE program would be expected to push term premia lower still, and might result in a capital loss for the Bank if the yields that bonds are purchased at do turn out to be lower than average future short-term rates."

"Might result". Understatement of the year!

It was a very costly blunder

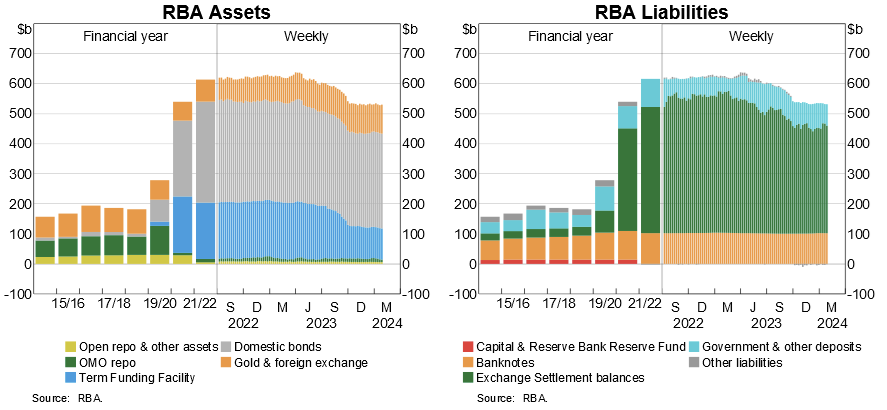

Despite its fancy name, QE is just the process of restructuring the maturity of government debt held by the private sector. The RBA buys long-duration federal and state government bonds on the market in return for short-duration "exchange settlement (ES) balances", which are equivalent to cash held on deposit with the RBA. It then pays interest on those ES balances to prevent rates from falling too far below its cash rate target (see here for an explainer).

The RBA's own charts show this effect in action, with the surge in bond purchases on the asset side matched very closely by growing ES balances on the liability side on its balance sheet:

Given that our federal and state governments were adding debt at a much faster rate than the RBA was buying bonds, and that Australia is very exposed to global financial markets, it's unlikely the RBA's QE had much of an impact on duration or yields. What it did do was send a signal; a signal that the RBA was serious about keeping rates down for a long time, encouraging people to take on more debt than they otherwise might have. If we were going through a financial crisis, that probably would have been OK, but the pandemic was mostly a negative supply shock. To ease a supply shock you need supply-side reform and fiscal restraint, not demand-side stimulus such as QE.

As a result, QE resulted in large costs.

First, it raised asset prices and inflation (which the RBA considered to be a benefit at the time), and imposed a burden on those who believed the signal and over-levered themselves ahead of a sharp monetary tightening cycle.

Second, bond yields move inversely to prices, and as discussed earlier QE just swapped some of the private sector's lending to the government from bonds to ES balances at the RBA. When inflation showed up and the RBA eventually started tightening monetary conditions, the low-yielding bonds it bought at record-high prices were worth much less. To credibly tighten monetary policy, the RBA also had to start paying higher rates of interest on ES balances than it receives from those bonds.

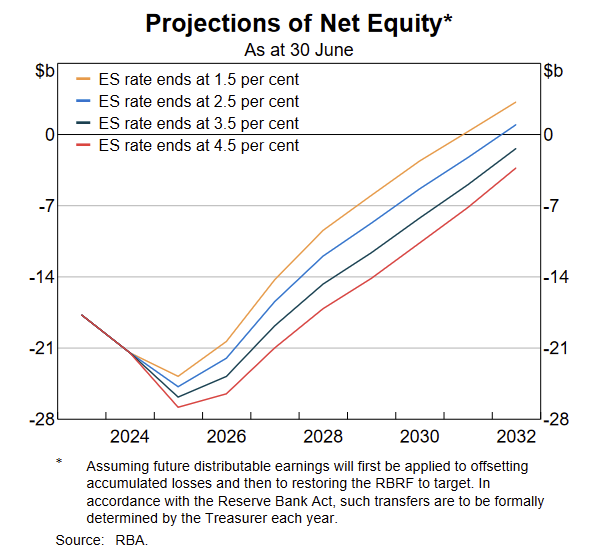

That second effect has led to large losses: as at 30 June 2023, the RBA had lost a cumulative $17.7 billion due to the unrealised valuation losses on its holding of bonds and from the interest it pays on ES balances.

But despite being technically insolvent, the RBA is not at risk of insolvency, because its liabilities are guaranteed by the federal government (section 77 of the Reserve Bank Act) and it can literally print money:

"As a central bank, the RBA also has the ability to create liquidity to meet its liabilities as and when they fall due and has substantial liabilities (in the form of banknotes on issue) that have a zero funding cost."

While many of the RBA's losses remain unrealised and will fall over time as its bonds approach maturity and tend towards face value (the RBA paid above face value, so will realise losses of at least $19 billion), it's still very real from a taxpayer's perspective. For example, the RBA will not be able to pay what is normally a multi-billion dollar dividend to the government for some time – the bank expects that it could take over a decade before it returns to positive net equity.

If inflation proves to be persistent and the RBA has to hold rates at present levels, or raises them even more – as New Zealand's central bank might be about to do – then the losses it realises on ES balances will continue to grow until the final bond rolls off the RBA's balance sheet in 2033. The RBA's own estimates suggest it could lose between $35 to $58 billion on ES balances by 2033. Add that to the guaranteed $19 billion loss on its bonds and the total fiscal cost will be above $50 billion.

Using the RBA's lower estimate, that's still over $5,500 for every Aussie household resulting from a decision made by unelected officials who had several months to think about it (other countries started doing their own versions in March 2020) yet did not bother asking their small army of analysts for so much as a cost benefit analysis.

Lessons for the future

To its credit, the RBA appears to have taken steps to ensure similar mistakes aren't made in the future. For example, in its review of the QE program the RBA's board:

"...has agreed to strengthen the way it considers a wide range of scenarios when making monetary policy decisions in future, especially where they involve unconventional policy measures. In relation to any future BPP [bond purchase program], this scenario analysis would include the benefits and potential costs of the policy, recognising the difficulties in measuring these outcomes."

Still, it's not clear that the RBA, as an organisation, has learned enough to avoid the global group think that led it to adopt QE in the first place. The government's recent changes to the RBA Act, modelled on the governance being used by other central banks that also failed to foresee the problems of QE and the inflationary crisis, is unlikely to make a material difference – although the increased transparency is welcome, and might cause the governor to think twice before going down the "unconventional" road in a hurry.

But the RBA still operates in a bubble. Many employees start and finish their careers at the RBA, perhaps with brief stints overseas at another central bank. Former governor Lowe joined straight out of high school. His replacement, Michele Bullock, started there as an intern after completing her degree. They attend central banker conferences, and read literature written by central bankers. Don't get me wrong; this isn't a problem unique to Australia. But it's still a problem.

As the saying goes, 'it's tough to make predictions, especially about the future'. I don't pretend to have a solution, only that I tend to favour rules-based over discretionary-based monetary policy. While a more rules-based monetary policy – whether it be something like the Taylor Rule, or even NGDP targeting – would inevitably still result in errors, it's more likely to prevent the large-scale damage caused by "unconventional", discretionary policies that were based on prediction errors, such as those delivered by the RBA and most other global central banks between 2020 and 2022.

Member discussion