Powering our AI future

If Australia's policymakers don't address the rising energy demands of AI, we risk falling behind other advanced nations. Despite its many critics, nuclear is a potential solution alongside renewables, and should not be ruled out so cavalierly.

I don't know how closely you've been following the AI scene but let me tell you that it's trucking along at a blistering pace. Large language models (LLMs) have moved well beyond text chat interfaces and are now even being tested in robotics, with OpenAI's latest demo looking very impressive. Sure, it's in a controlled environment, probably cost a small fortune, and we don't know how much assistance OpenAI truly provided to "Figure 01" – despite the name, OpenAI is quite a secretive company – but if LLMs are eventually able to improve the field of robotics, then the productivity possibilities are endless.

Which raises the question: are we ready? And I'm not talking about whether we, as a country, are ready to embrace AI; I have no doubt that it's already being used widely – especially by Gen Z – and they'll warm to it as easily as older generations did the internet. What I want to know is whether our institutions and infrastructure are ready for AI.

It's all about power

AI uses a huge amount of energy and that looks set to only increase going forward, with the chip shortage being solved by increased power consumption:

"Dell let slip during their earnings call that the Nvidia B100 Blackwell will have a 1000W draw, that's a 40% increase over the H100. The current compute bottleneck will start to disappear by the end of this year and be gone by the end of 2025. After that, it's all about power."

The IEA's 2024 report predicted that "[e]lectricity consumption from data centres, artificial intelligence and the cryptocurrency sector could double by 2026", with data centres alone adding the equivalent of the electricity consumption of Japan to demand in the next two years.

If the AI bottleneck moves from compute to power, then it means energy abundance will be needed for Australia to be competitive in an AI future. And energy isn't exactly an area in which we've excelled; according to a 2019 report by the Commonwealth's Standing Committee on Environment and Energy:

"Australia has been gradually losing a competitive advantage in the cost of electricity, with adverse consequences for Australian households and Australian industry, especially manufacturing... Australia has been experiencing long term trends of increasing wholesale and domestic electricity prices... [and] Australian household electricity prices have gone from one of the cheapest in the OECD to one of the most expensive."

If we no longer have a competitive advantage in energy generation, what chance do we have of attracting new, energy-intensive industries to our shores? If you're not in the business of physically digging something out of the ground, or are otherwise required to operate in Australia, then you don't; you go to a country where your business has a better chance to survive in the cutthroat world of frontier technology.

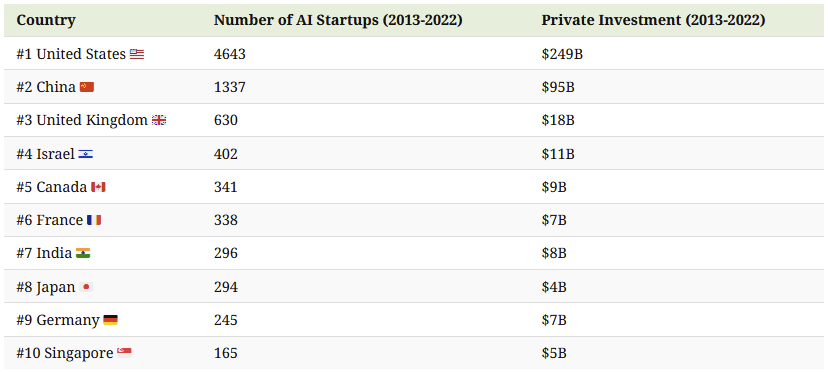

We should be more like Canada

Notice that country #5 on that list is Canada, a nation with a similar institutional heritage to Australia, i.e., an English-speaking Commonwealth with a legal foundation based on British common law. Without question, Canada has a huge advantage over Australia in its proximity to the world's most prosperous country, the US. But in the context of embracing AI, its main point of differentiation is in its energy policy:

"Canadian energy policy has significantly contributed to the development of the energy sector, which is a major driver of Canada's economic growth and well-being. As a large exporter of energy, Canada is an important contributor to North American and global energy security. Canada has demonstrated a strong determination in implementing reforms to improve the performance of its energy sector and it is a leader in several fields of energy technology."

Unlike Australia, Canada's federal and provincial political leaders have managed to pass revenue neutral carbon taxes (making renewables and nuclear competitive against fossil fuels), ensuring that the transition to net zero happens far more efficiently than our solution of picking winners and losers through the political allocation of tax credits, subsidies and government investment funds.

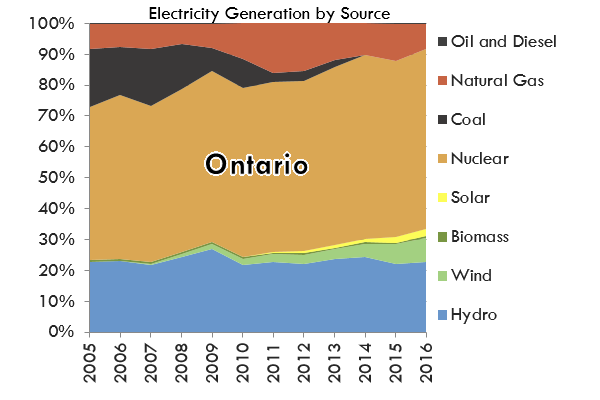

While the Canadians are geographically fortunate in the sense that they have a lot of mountains and fresh water to fuel a considerable amount of affordable, green hydro power, they also embraced nuclear. Nuclear energy is now the leading source of power in its largest province, Ontario, where coal was completely phased out in 2014. Today, electricity prices faced by households are around a third of what we pay in Australia.

The most reliable, affordable energy source for Australia is of course still coal, but it's also dirty and kills far more people than the alternatives; its 'social licence' has been revoked. But unlike Ontario, Australia has refused to even consider nuclear as a replacement for coal.

Nuclear shouldn't be ruled out

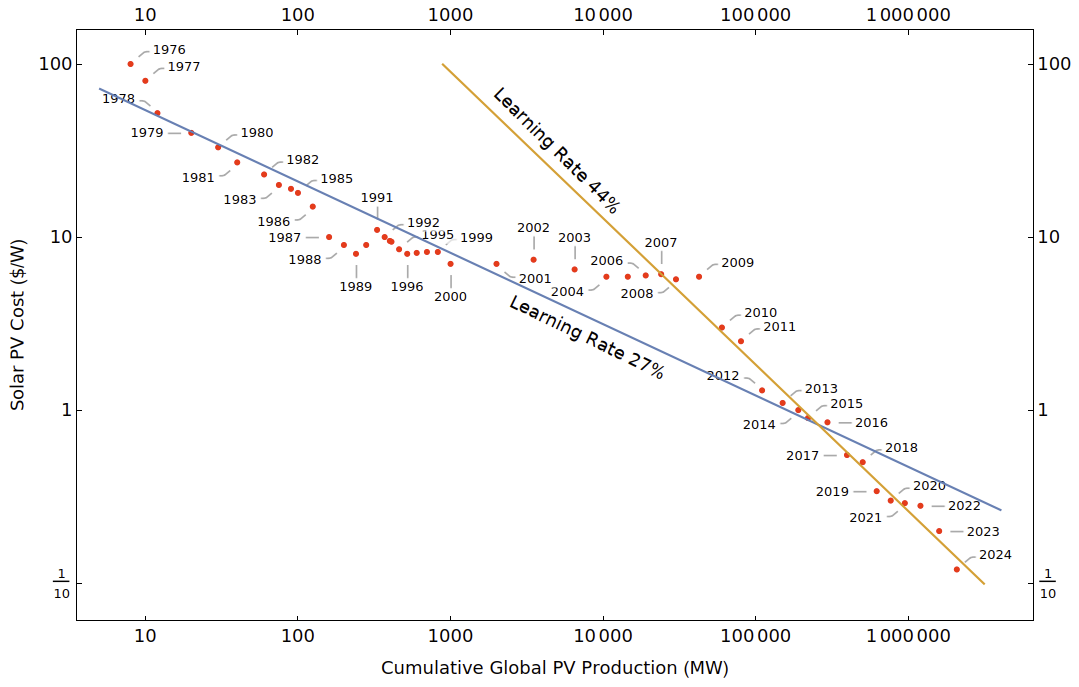

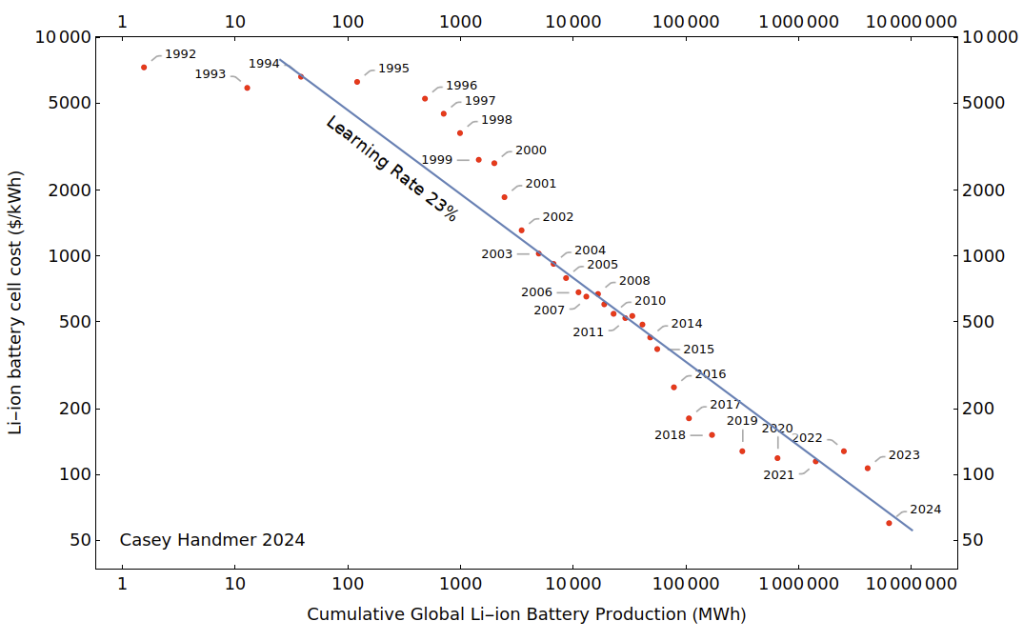

To power AI will require an efficient, clean and more importantly, reliable source of energy. Renewables could plausibly fill the void left by coal – the decline in solar and battery prices has been quite remarkable – but they have also been plagued by issues of intermittency, storage and uncertain transmission costs.

Powering AI and the huge data centres needed to store the sheer volume of data they need to operate requires 100% uptime, and nuclear could be one of the "missing pieces of the clean energy portfolio where we need firm clean power to provide that backup to wind and solar".

Such requirements are why a massive new Amazon Web Services' data centre decided to locate right next to a 2.5 gigawatt nuclear power station:

"The 1,075-acre Susquehanna Steam Electric Station is the sixth-largest nuclear power plant in the US. It's been online since 1983 and produces 63 million kilowatt hours per day. The plant has two General Electric boiling water reactors within a Mark II containment building that are licensed through 2042 and 2044.

According to Talen Energy's investor presentation, it will supply fixed-price nuclear power to Amazon's new data centre as it's built. Amazon has minimum contractual power commitments that ramp up in 120 MW increments over several years. The cloud service giant has a one-time option to cap commitments at 480 MW and two 10-year extension options tied to nuclear license renewals."

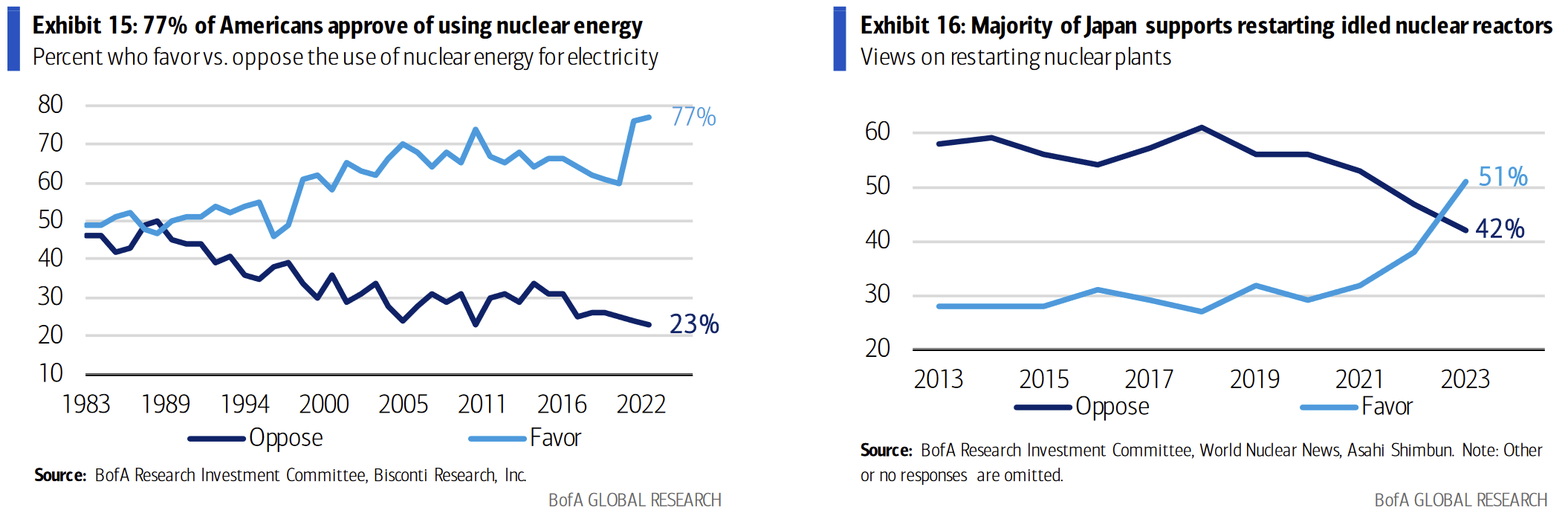

Like Australia, the US developed a deep-seated aversion to nuclear following the Boomer-era anti-nuclear, environmental activism days. But the tide of public opinion has changed and bipartisan support for nuclear is growing, meaning the US – and Australia – could move back in that direction. In the US, Congress has already injected billions of dollars and modernised nuclear regulations, setting the stage for a nuclear revival.

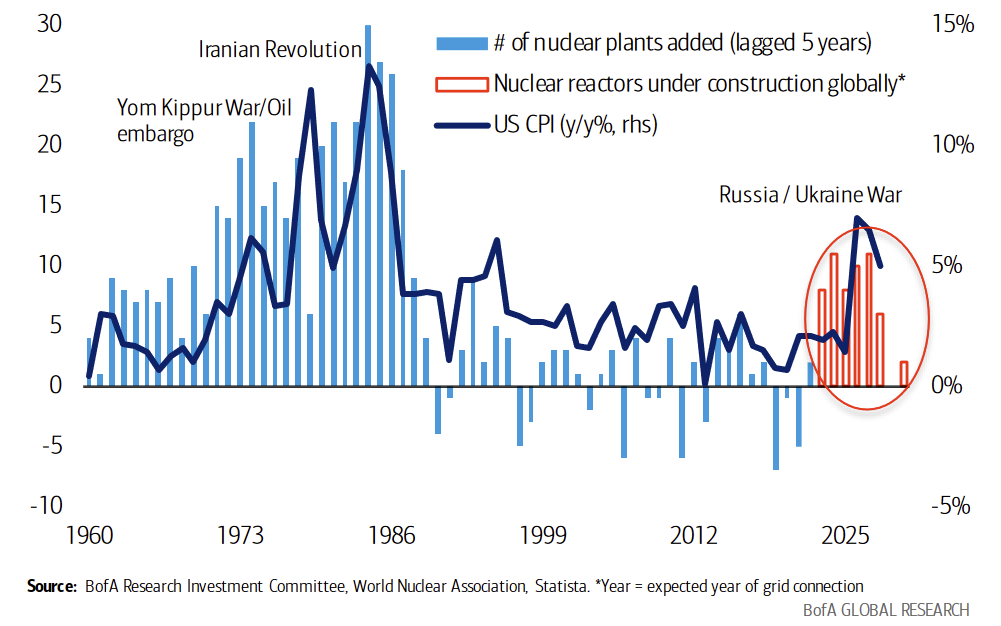

The rest of the world is also warming to nuclear. According to the IEA, "nuclear generation is forecast to grow by close to 3% per year on average through 2026 as maintenance works are completed within France, Japan restarts nuclear production at several power plants, and new reactors begin commercial operations in various markets, including China, India, Korea, and Europe", and there are currently 60 brand new nuclear reactors being constructed across 16 countries.

The lack of a nuclear discussion in Australia has been a political, not economic choice. Regarding energy policy, I found a recent conversation between a16z Co-founder Marc Andreessen and economist Tyler Cowen especially illuminating:

"[N]uclear fission, for sure, is the most underrated [energy source] today... We ought to be doing what Richard Nixon proposed in 1971, right? We ought to build what he called project independence, which was to build 1,000 new nuclear power plants in the US and then cut the entire US grid over to nuclear and electricity, go to all-electric cars, do everything else. Richard Nixon's other, you know, great corresponding, you know, creation of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, of course, guarantees that won't happen. The plan is exactly on track. But we could. And so either with existing, you know, nuclear fission technology, or there's actually a significant number, you know, new nuclear fission startups, as well as fusion startups working on new designs. And so this [AI] would certainly be a great use case for that."

Thankfully, in Australia the Liberals don't look like they're going to ease up on the nuclear issue prior to the election, pushing the idea "that nuclear power is better [for some people] than having their areas covered with power lines and wind farms".

Whatever their motives, it's a good thing when debate happens: as the great physicist Richard Feynman said, "I would rather have questions that can't be answered than answers that can't be questioned."

Answers that can't be questioned

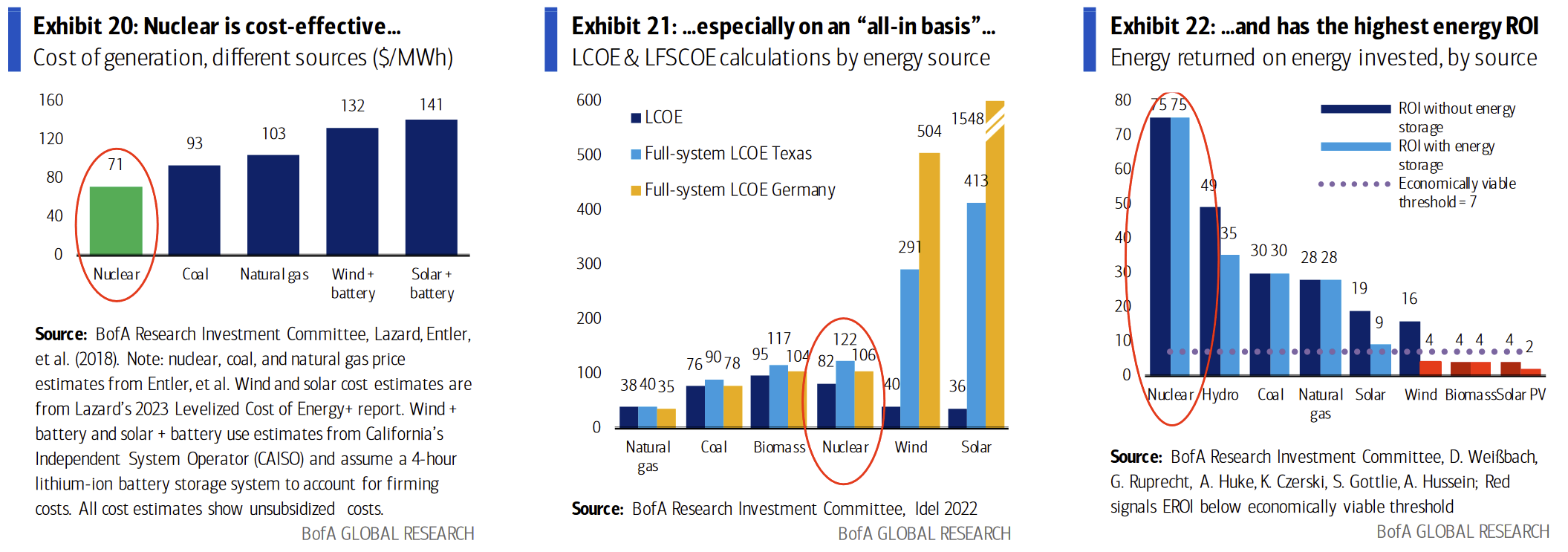

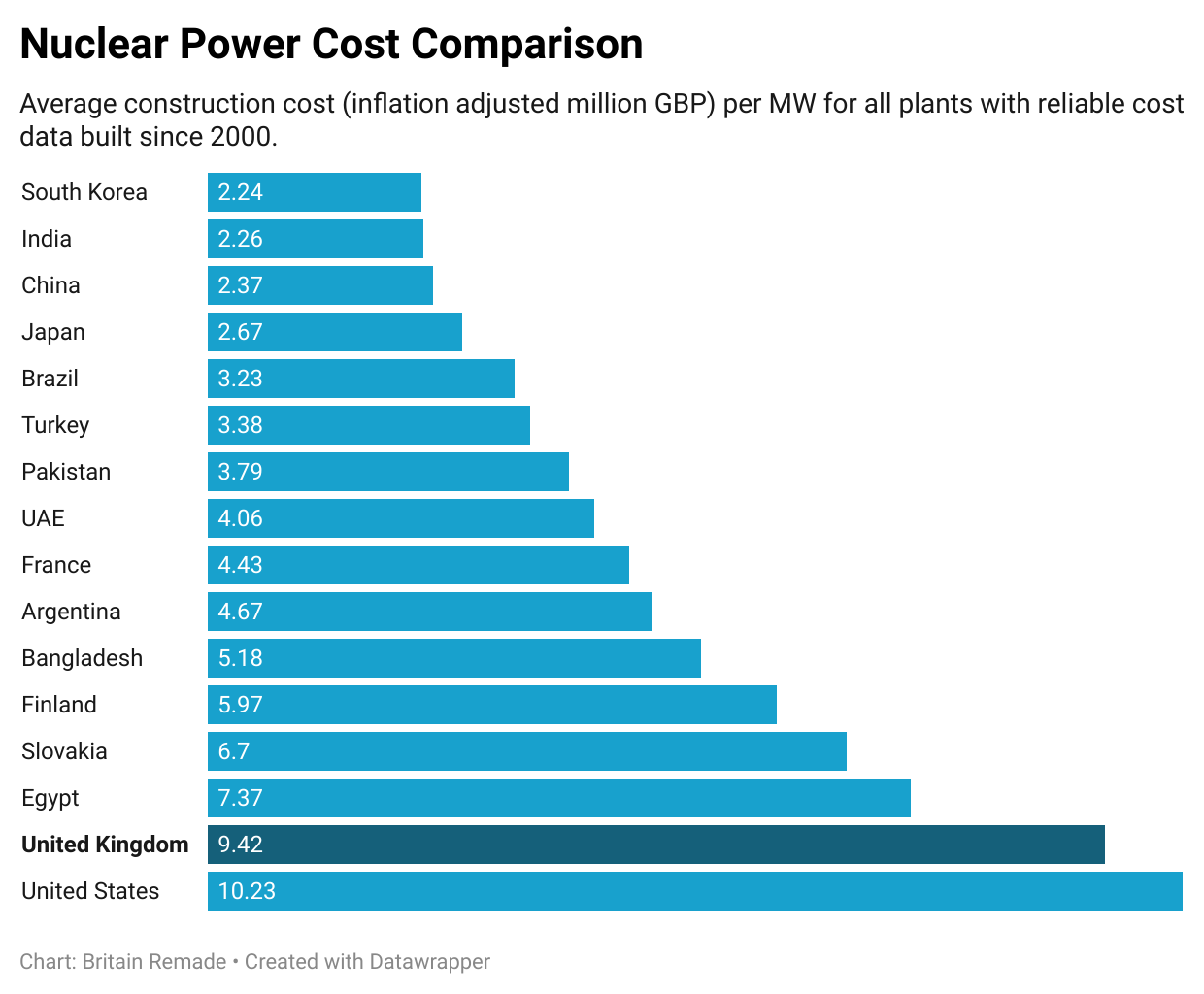

We don't know whether nuclear will or won't work in Australia. Our Energy Minister, Chris Bowen, likes to call it "the most expensive form of energy". But his source is a single report written by the CSIRO, called GenCost, which based its comparisons on one failed small modular reactor in the US , the country with the world's most expensive nuclear power of any kind, and concluded that nuclear makes no sense for Australia.

The GenCost report has now attracted so much scrutiny for its questionable assumptions that CSIRO's CEO, Douglas Hilton, felt the need to publish a short letter on Friday "staunchly defend[ing] our scientists and our organisation against unfounded criticism".

Contra Hilton, challenging the report's methodology does not "disparage science"; it strengthens it. The fact that the CSIRO's no doubt well-qualified economists and scientists believe that nuclear is too expensive for Australia provides one piece of evidence that deserves serious consideration. But that's all it is, and Hilton's response – effectively saying that GenCost provides "answers that can't be questioned" – raises serious alarms about the scientific integrity of that organisation.

Perhaps GenCost will be a useful resource at some point in the future; I don't know. But it has been treated as fact by sitting Ministers such as Bowen – as 'the science' – when it's clearly a work in progress and should be treated with an appropriate amount of caution and scrutiny, given its importance to energy policy. Especially when there's contrary evidence out there, such as a recent Bank of America report that found nuclear to be very cost competitive.

As stated in the report, "factors like natural gas or expensive battery backup power for solar or wind farms" are not adequately considered by the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) measure used by GenCost. What we should be comparing when looking at an energy transition and its impact on consumers are the full system costs "that include balancing and supply obligations", and if we do that then nuclear starts to look quite attractive.

A nuclear strategy

It won't be easy to start a nuclear industry in Australia. Off the top of my head, we would need to:

- legalise it;

- regulate it;

- hire hundreds of overseas experts to staff it, given we haven't been training nuclear engineers in Australia, for good reason – where would they work;

- find appropriate sites, which could be difficult given AGL, the biggest owner of coal-fired power stations in Australia, said it doesn't want nuclear at its old coal sites; and

- perhaps most challenging of all, overcome the inevitable resistance from NIMBYs, e.g. "we don't want nuclear waste travelling down our highways".

Fortunately, other countries have been doing most of these things for decades, so we can do a China and play regulatory and technological catch-up to solve most of them. We can also look to countries where nuclear is the most economical and see what they did right; by starting from scratch, we can avoid the pitfalls of countries such as the US and UK, and instead learn from South Korea or Japan.

The hardest part, by far, will be overcoming NIMBYism, although that's not a problem unique to nuclear. As I wrote back in January, our renewable transition is already in trouble because there's nowhere to build the damn stuff without people complaining:

"Those opposed to renewable projects, whether ideologically or for NIMBY reasons, are going to slow progress towards net zero by using the same tools environmentalists have been using for decades to slow and raise the cost of fossil fuel projects. Noise, aesthetics, tourism, recreation, wildlife, habitats, danger, lightning, their way of life – you name it, and you can be sure it will be trotted out in opposition of these projects during "community consultation", often without any evidence at all. They don't have to be right: they just have to delay projects for long enough to make them prohibitive.

If nothing is done to prevent such tactics, which create huge costs for investors and governments in terms of uncertainty and potential delays, we're going to be forced to run what's left of our old, dirty and dilapidated coal-fired plants (who would invest when the government has effectively ordered them to shutter) for a whole lot longer than necessary. It's always about trade-offs, and when someone blocks green energy in their backyard, they're probably creating pollution in someone else's."

Whatever strategies our political leaders have to get past those hurdles – and to meet their targets, they'll need plenty – could just as easily be applied to nuclear. Unless they don't have a strategy at all; the political cycle is fast, while the energy transition will be gradual. And the transition doesn't necessarily need to be credible all the way to 2050, it just needs to be credible enough to survive the next election, after which you can blame your predecessor or kick the can out another few years.

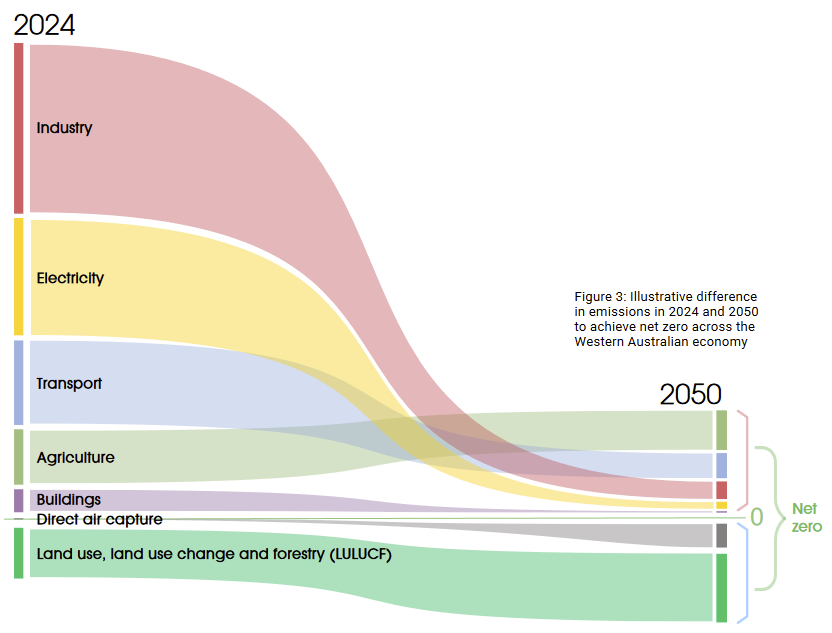

Such incentives are why you get strategies such as the one released late last year by the WA government, where almost all of the transition to net zero is back ended so far into the future, with no X axis and the modelling withheld, that no sitting politician will pay any political cost if (or when) it's not met.

It's just pure choice

If we want to maintain our standard of living and improve the prospect of higher real wages for the next generations, then we need to improve our productivity and one way to do that is through technological innovation. We don't even have to invent the stuff here; we just need to be capable of using it – to transfer and diffuse it through our economy. I'm once again drawn to Marc Andreessen, who said:

"Again, and energy is just pure choice. Like, you know, we could be building, you know, 1,000 nuclear plants tomorrow. My favourite idea there, which always gets me in trouble, and so I can't resist is, so the Democrats administration should give Koch Industries the contract to build 1,000 nuclear reactors, right? Everybody gets revenge on everybody else. The Democrats get Charles Koch to fix climate change, and then Charles gets all the money for the contracts. And so it's kind of, everybody ends up happy."

For that to work in Australia you would have to flip the roles, given that it's our left-of-centre Labor party – the Democrat equivalent – that's opposed to nuclear, not our right-of-centre party, as it is in the US. But regardless, it shows that Marc is thinking about the political incentives: how can we do this and make everyone better off?

We have a choice to make in Australia. Do we want to embrace AI, or do we want to be left behind, relying on the export of raw commodities while the rest of our economy stagnates, Dutch disease-style? Businesses simply won't be able to exploit AI competitively without improving our energy affordability and reliability; governments and companies won't want their in-house AI, which will need to be trained on sensitive data to be useful, to be stored overseas. That means we need a lot more data centre capacity in Australia, even if we struggle to attract actual AI companies to set up shop here. Add in the energy needed to run the AI itself, and we will need a lot more power than our current transition to renewables may be able to provide.

What we shouldn't do is rule out nuclear energy based on the findings of a single report that the government has declared beyond reproach. Legalise nuclear, ideally alongside a revenue-neutral carbon tax, and if renewables and battery storage perform as well as Bowen expects, then nuclear power will never be competitive, he can give us all a big "I told you so", and we can get on with our AI-powered lives. But if he's wrong, his mocking dismissals and refusal to even consider the idea could set us back decades.