Rethinking the National Broadband Network

The NBN was a costly mistake that has failed to earn a commercial return, hindered competition, and its business model is being undermined by new technologies. Might it be time to rethink the experiment?

Please excuse me if the tone in this post is a bit harsher than usual but I spent all of Monday dealing with my internet provider, which was itself dealing with our local broadband monopoly, the National Broadband Network (NBN) Co, about my persistent lack of internet.

It was a frustrating experience, to say the least, given that I pay for "business grade" broadband – tell me what business can go without internet for an entire day? I certainly can't. But not wanting to waste a learning opportunity, at least the whole debacle inspired me to do a bit of digging, via a high-speed 5G hotspot connection on my mobile phone, into how and why we ended up with the government-owned corporate monopoly we have today, NBN Co, and what we can do to improve it.

"My greatest contribution"

If you're not familiar with the history of the NBN, folklore has that it was conceived by then-Communications Minister Stephen Conroy, who scribbled the idea on the back of a napkin when he and then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd were travelling on a plane together. The plan was rumoured to look something like this:

I jest, of course; the napkin has never been revealed, and Conroy denies its existence. But regardless of how the concept was formed, several months later the national broadband network – what would become NBN Co – was born.

Slated to cost $37.4 billion in capital expenditure in a public private partnership, complete its national fibre to the premise (FTTP) rollout by June 2021, and provide the government with an impressive annual internal rate of return of 7.1%, it was "to radically change the way that business is done in Australia".

Conroy, when he resigned from the Senate in 2016, stated that "the National Broadband Network will remain my greatest contribution". And that's saying something, coming from the guy who once boasted to an American investors that he had "unfettered legal power", and that:

"If I say to you everyone in this room, 'if you want to bid next week in our spectrum auction you better wear red underpants on your head', you'll be wearing them on your head."

Another great contribution was Conroy's public ridicule of iiNet's legal defence against Hollywood (which iiNet won, by the way), and who could forget his attempts to build a mandatory national filter that would even have impressed China and its 'Great Firewall'.

To be fair, the Liberals of that day weren't much better, albeit in the other direction. Shortly after becoming Prime Minister in 2013 – yes, only around a decade ago (we really churned through PMs for a while there) – Tony Abbott claimed that:

"We are absolutely confident 25 megs is going to be enough – more than enough – for the average household."

Oof. That gaffe puts Abbott right up there with the great economist Irving Fisher, who proclaimed in 1929 that stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau", right before they crashed 89% (seriously though, don't take investment advice from economists).

But I digress. At the time, Labor thought they were onto a winner with the NBN. However, as can often happen when governments try to pick winners, they create losers instead. Today, the NBN is more synonymous with complaints from users of all political stripes, whether due to its glacially slow rollout, poor speeds, high costs, or frustrating lack of reliability (as I experienced on Monday).

And yes, our fixed-line broadband internet is really that bad. According to the World Broadband Association's 2023 report:

"Australia's challenges in broadband are widespread, given it has below-average scores in all three broadband segments. The country's broadband access score is pulled down by relatively low FTTP coverage of 26% and FTTP penetration of 17%, although it is helped by 79% of households having broadband service. The low fibre penetration is one of the factors behind the country's low score in broadband usage and application, given that fewer than one quarter of the country's residential broadband connections provide 100Mbps or faster speeds, based on Omdia's analysis. Its broadband potential score, meanwhile, is impacted by below-average broadband affordability."

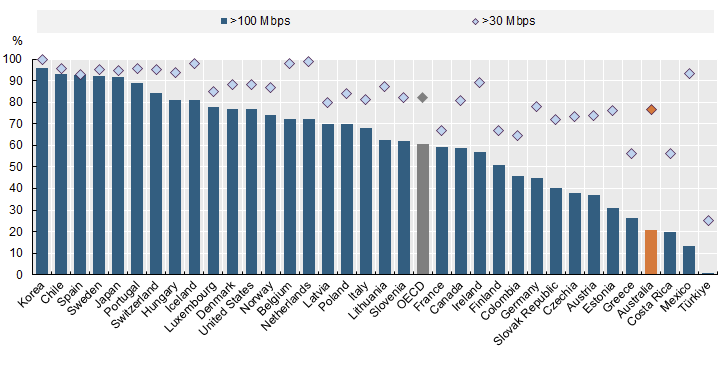

As at December 2022, our internet ranked as one of the slowest in the OECD in terms of the percentage of fixed broadband subscriptions with speeds faster than 100Mbps, which was achievable with the technology Optus and Telstra were already using prior to the NBN (Hybrid Fibre Coaxial, or HFC, more commonly known as cable).

Not all of this is the fault of Labor, or the NBN Co. In 2013, Abbott's Liberal Party scrapped the plan for near-universal FTTP but otherwise left the existing market structure intact, effectively condemning us to slow and inefficient fixed-line broadband, rather than just inefficient.

Ultimately, the cause of our relatively poor internet performance lies in the way the policies governing the NBN, and Telstra before it, were conceived, designed and then modified over the years by various politicians.