Kamala's policy-pocalypse

I was going to kick the week off with a post on the Reserve Bank of Australia given all the public speaking it has been doing, but that's going to have to wait until Wednesday's Paid post because the US election just got a whole lot more interesting.

Normally I wouldn't write a full post about a US political candidate, but for whatever reason our current government loves to copy what they do over there – whether it be industrial policy, emissions standards, or even how it spies on us – so I thought I should get ahead of this one. We do, after all, have half a dozen ongoing supermarket inquiries, and presumably at least one of them will look at what the US is doing and just copy-paste that into their recommendations.

So when I saw that, after a month of riding on nothing but vibes to become odds-on favourite to become the first black, Indian, female US President (53% to Trump's 46%), the Democratic nominee Kamala Harris finally revealed an actually policy proposal, I had to take a look. And then she went and announced four!

- No taxes on tips (also backed by Trump).

- Stricter rules – price controls and merger restrictions – against alleged price gouging in the food industry.

- Expanded price controls on pharmaceuticals to reduce drug prices.

- A $25,000 first home buyers grant.

If I was asked to compile a list of policies that would do absolutely nothing to solve the actual, underlying problems they claim to address, but would instead create a myriad of unintended consequences, the four Harris unveiled on Friday night would be near the top of that list.

These policies upset more than a few people, including supporters of Harris. Democratic blogger Noah Smith called the price controls a "big mistake", while former Bush Administration Chief Economist and popular textbook author, Greg Mankiw – who intends to vote for Harris – wrote that "every time Harris says something specific about economic policy, she makes my voting for her more painful":

"I read that, in the coming days, Harris plans to be vague about her policy plans. I hope that is true because by advocating specific ill-advised (if politically attractive) policies during the campaign, she might feel compelled to follow through on them after she is elected. After the election, good policy is more likely to win out against good politics. At least I hope so."

It's no wonder that these prominent Harris voters are begging her to please stop telling people about her policy ideas until after the election, so they can keep the good vibes going and not feel bad about their decision to vote for her.

That's because Harris' proposals truly are the four horsemen of a policy-pocalypse.

Tipping culture rots the brain

The first policy proposal isn't really relevant for us down here in Australia because – certain rideshare and food delivery apps notwithstanding – tipping isn't a thing here. But it's still a bad idea not to tax tips, because:

- any benefits will accrue to bosses, not workers, limiting the benefits; and

- a lot of wage income will miraculously be reclassified as a tip, with the revenue shortfall replaced with potentially less efficient taxes elsewhere.

If anything, tips should be taxed more than wage income, because that's probably the only way to break the culture of tipping, which has not meaningfully incentivised service quality for a long time:

"In a 2009 Applied Economics article, Ofer Azar of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev reviewed several studies that examined the effect of customer service quality ratings on the size of tips. Those studies found that better service quality did increase tips but only by a little — not enough to be a meaningful incentive for workers. The disconnect between service quality and tip size is also evident in the fact that a tip is usually a percentage of the total bill, making tips larger at more expensive restaurants even though menu prices have little to do with service quality."

Most workers prefer tipping because it allows them to capture economic rents, but in doing so places a potentially confusing burden on customers to directly subsidise those workers' wages. It's also bad for restaurants, but most are forced to maintain the practice because it helps to keep menu prices down.

Selfishly, I'd love it if the US and Canada would get with the rest of the world and abandon tipping, because as a visitor the experience can be unpleasant. But they don't even use the metric system and if anything this policy will strengthen the cultural norm, so I doubt it'll ever change.

Please shelve the price controls

Have we learned nothing since Nixon? Quite literally on the anniversary of Nixon's implementation of his ruinous price controls, Kamala Harris announced plans for her own:

"With inflation and high grocery prices still frustrating many voters, Vice President Kamala Harris on Friday proposed a ban on 'price gouging' by food suppliers and grocery stores, as part of a broader agenda aimed at lowering the cost of housing, medicine, and food.

...

'We all know that prices went up during the pandemic when the supply chains shut down and failed', Harris said Friday in Raleigh, North Carolina. 'But our supply chains have now improved and prices are still too high'."

Prices are useful signals that help coordinate responses to changes in economic conditions. They convey information that creates an incentive for market actors to respond in socially beneficial ways. It's the reason why economists like to point out that the cure for high prices is high prices.

What Harris is proposing is government-dictated price ceilings. If the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) decides that prices are too high – "excessive prices that are unrelated to the costs of doing business" – it will be given the authority to reduce them to levels it deems reasonable.

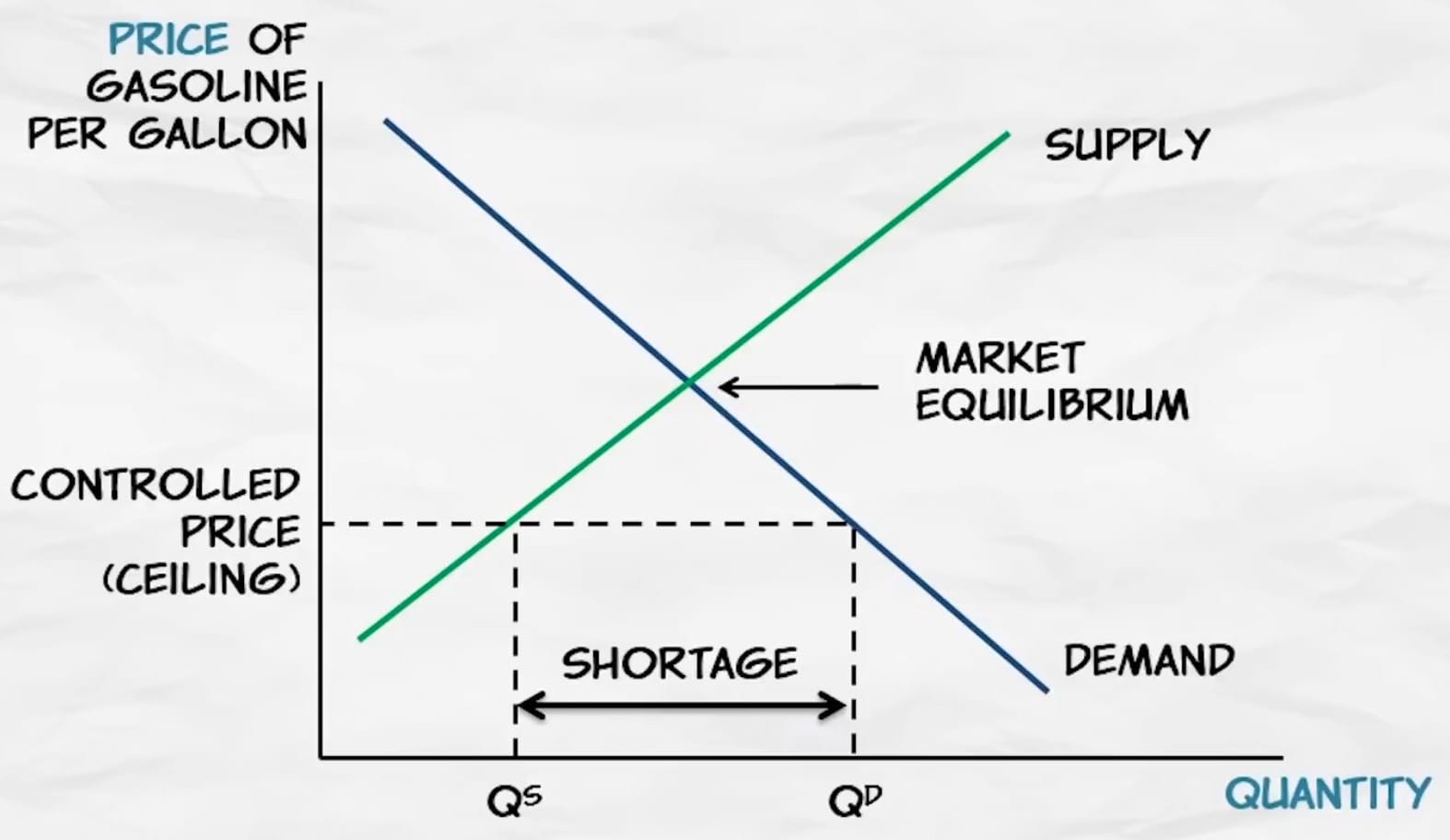

The biggest risk is that if prices are set too low, then firms will just stop selling the products or reduce quality; there's a reason why every economics textbook has a chart like this showing one risk of such a policy:

If businesses keep selling the products in question – notice quantity supplied, or Qs, doesn't go to zero because many firms will keep producing, at least for a while, because of their sunk fixed costs – then search costs will increase and queuing will take place. Basically, there's a huge loss in terms of forgone gains from trade, and a misallocation of resources.

There's more to prices than just the "costs of doing business", such as the cost of capital, which includes its opportunity costs. If Harris wants the FTC to regulate away profit, who would be stupid enough to invest in the food industry? If that's the bar, then the FTC will almost certainly set it too low. Empty shelves will ensue, because Harris will have killed the incentive for them to be stocked.

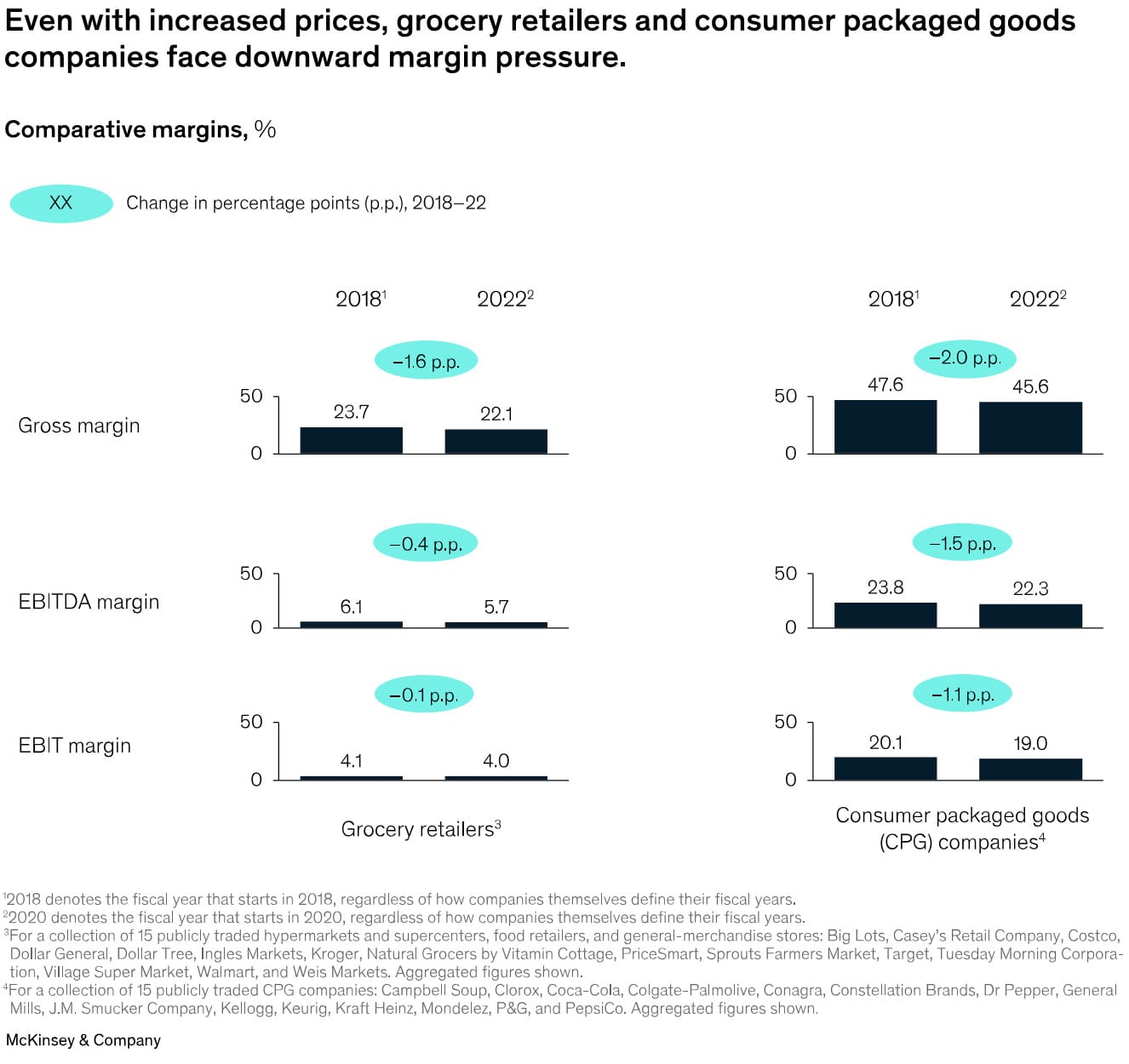

Instead of addressing the actual culprits – the big deficit-spending Trump and Biden administrations, along with a complicit Federal Reserve that worked together to stimulate demand to the point that it outstripped supply, so all prices rose together – Harris chose to blame "greedy" supermarkets, even though their margins are minuscule and were getting smaller when inflation was running rampant (even if they did increase, that's more likely to be indicative of rising aggregate demand – e.g. through expansionary monetary or fiscal policy – than price gouging):

It's just really bad policy, and is also the policy we're most at risk of seeing copied in Australia when these various supermarket inquiries wrap up – our politicians would love nothing more than to blame corporate greed for their own mistakes!

Free riding on US pharmaceuticals

You may not think that Harris' desire to cap prices on pharmaceutical drugs is that important for us in Australia, but it actually is. We – and the rest of the world – free-ride on the huge amount of spending the US drug companies pump into research and development (R&D). They spend so much in part because they're able to gouge US consumers with higher prices through the country's healthcare system, where treatments and drugs are often paid by someone other than the patient at inflated prices (public, private, or company-provided health insurance).

But price caps on pharmaceutical drugs will have a similar, albeit slightly different, effect as price caps on food. That's because the cost to produce most pharmaceutical drugs is a fraction of their price, and unlike food demand for them is relatively inelastic – consumers are relatively insensitive to the price because they're not paying and the drug is potentially life-saving with few, if any, substitutes.

So why are drugs so expensive if they cost so little to make? Not because of price gouging, but because it can cost billions of dollars to research and develop a new drug. If there was no price incentive – the ability to charge well above costs for a period of time – that R&D wouldn't happen, other than with the aid of government grants. And because Americans are so wealthy and willing to pay so much, almost all new drugs are developed for their market:

"Countries with single-payer systems often take one to two years to negotiate the price of a new drug. If a patent is granted for 20 years but the first 13 years are dedicated to development and approval, then only seven years of patent-protected sales remain.

If two years are added to that timeline for reimbursement negotiations, the interval drops to five years.If new drugs can make it in America, they are developed. If they can't, they aren't. Other countries are considered secondarily. They are the cherry on top; we're the sundae."

If Harris' drug price controls are passed, US consumers will enjoy cheaper drugs in the short-term. But the long-run effects could be devastating: by one estimate, "73% of the actual increase in life expectancy at birth... [was] due to the increase in the fraction of drugs consumed that were launched after 1990".

Fewer new drugs could mean shorter (potentially more painful) lives and more spending on physicians and hospitals. As Australians, we should want to continue free-riding off American investment in drugs – but we can't do that if the Americans get off the ride!

Does US patent law need to be reviewed, to balanced it more in favour of consumers rather than pharmaceutical companies, without disincentivising R&D? Probably. But that's not what Harris is proposing here.

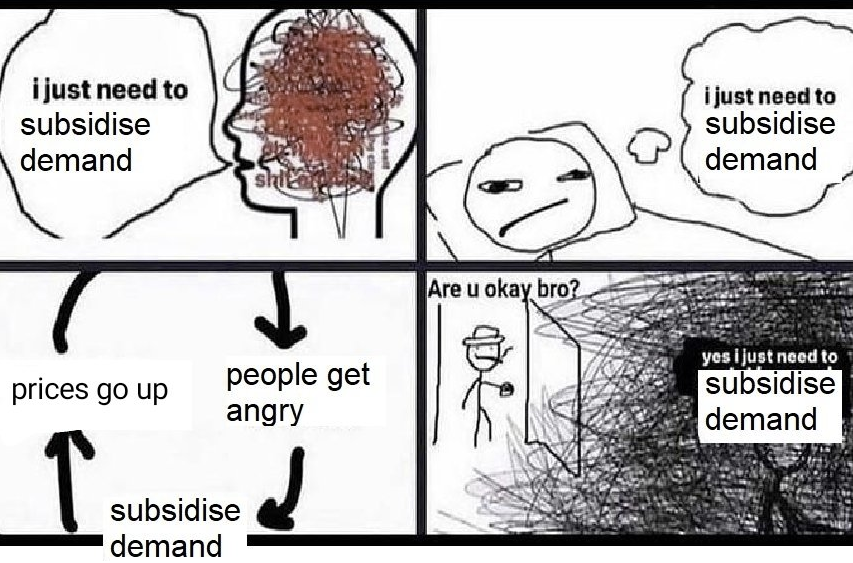

I must stimulate demand!

The last of Harris' four-pronged policy-pocalypse will be familiar to Aussies: first home buyer grants!

First home buyer incentives add to demand. When supply is inelastic – i.e. when higher prices don't incentivise much (if any) new supply – such grants will only serve to raise prices for the benefit of "the sellers who receive a higher sale price". In the US, about a quarter of homes are in areas where regulation prohibits a supply response, so the grants will fuel higher prices and do nothing to improve affordability in those regions:

"US housing markets are classified into three different groups: those with market prices well below minimum profitable production costs (MPPC); those with prices near MPPC; and those with prices well above MPPC. The first group contains cities such as Detroit that were built during more successful times and now have an abundance of durable housing that is cheap because demand has fallen. These areas are almost all losing population, so builders have little incentive to provide new housing at current prices.

In contrast, housing supply is constrained by limited land availability and land use regulations in America's pricier metropolitan areas, which make up the third set of markets. In these places, it is the political economy of land use controls that accounts for the (positive) divergence between market prices and fundamental production costs. In the rest of the country, housing markets are best characterised by the classic textbook example of demand intersecting a highly elastic supply curve, so that prices are pinned down by minimum profitable production costs.

A conservative estimate is that more than three-quarters of home owners across a wide range of 98 metropolitan areas we analyse presently live in homes that are valued around or below minimum profitable production costs."

So, buyers in cities like Detroit will benefit from Harris' first home owner grants, while sellers in cities like San Francisco will see their profits increase by another... well, $25k.

The relevant policy question is whether subsidising a subset of buyers in places where housing is already affordable, and wealthy sellers in places where it's not, is a good use of tax dollars. Given that the private benefits of home ownership are likely greater than the public benefits, that's dubious at best: from a welfare point of view there are plenty of other areas where that spending could be used to improve well-being by considerably more, such as supporting the homeless or low income households in rental, public or community housing.

If Harris truly wanted to improve home ownership rates while also assisting disadvantaged groups – with almost no fiscal cost – she should ease restrictive zoning, onerous building codes, and local government obstructionism, thereby permitting a greater supply of affordable homes. The Biden administration recently announced some efforts on that front, including "expediting housing permit approvals", which is of course good news but it's also not a Harris policy – Biden's already doing it.

That leaves Harris with demand stimulus and price controls, none of which will solve the problems they claim to address. I suspect that's because they were announced not for their economic impact, but because they poll well with a cohort whose votes she's hoping to swing in the forthcoming election; a true triumph of populism over policy.

Member discussion