Oz Econ Pulse: Peter Dutton, Tradie shortage, Donald-25 mind virus, and Economists against tariffs

No doubt many of you are still enjoying a long Easter/ANZAC Day break, but for those of you pining for some economic news, here are a few bits of interest that caught my eye this week—starting with my comprehensive essay on Peter Dutton.

Peter Dutton is a man without a plan

If you missed my Deep Dive into Peter Dutton and his Liberal Party earlier this week, here's a slice from beyond the paywall:

"Dutton's return-to-office mandate was a loser from the get-go, yet he stuck with it for months before embarrassingly throwing in the towel and admitting that "we made a mistake".

Regardless of what you might personally feel about working from home, there's strong evidence that flexible working arrangements:

- reduce office and wage costs (more on that below);

- improve recruitment and lower retention costs, and staff attendance (fewer sick days);

- cut congestion and pollution through less commuting; and

- support those with care and disability challenges.

Yes, that's all also true for government workers. And in Australia specifically, there's "no significant difference in productivity between employees who work from home and those in the office".

Dutton wasn't helped by the fact that, when announcing the policy, his shadow finance minister Jane Hume "cited research that actually endorses partial work from home". And that women with young children are the most likely people to be taking advantage of remote work—and Dutton already had a women problem.

As with taking a hatchet to the public sector, it all just reeks of policy on the fly—Trump did it, so we should too... until we didn't want to be associated with him anymore, so now it's no longer Liberal policy."

Read the full essay to see why Dutton's policy missteps are turning voters away.

Australia's tradie shortage

Alan Kohler wrote that Australia's apprenticeship system appears to be broken, and that "the shortage of tradies is at the heart of the housing crisis":

"The starting wage for an apprentice is $598.80 a week, or $31,176.60 per year. No wonder many of them don't last.

The National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) reports that in the September quarter of 2024, trade commencements fell 17.4 per cent overall, with the largest fall (18.6 per cent) in construction.

As at September 30, there were 333,765 active apprentice and trainee contracts nationally, a drop of 7.8 per cent compared with the year before.

And the completion rate has fallen 54.8 per cent, with only 40 per cent finishing with the same employer.

Both major parties are proposing to put more money into apprenticeships — Labor, $10,000 each; Coalition, $12,000."

Intuitively I was inclined to agree, at least with the tradie part—everyone knows how hard it is to find a reliable tradie these days, and governments are constantly blaming "labour shortages" for their construction project blowouts.

But I've been around long enough to know not to trust percentages alone—especially not when reported by a journalist. So, I went and had a look at the original data Kohler cited above. It turns out that the fall he's citing isn't actually for trades at all; it includes all "trade and non-trade occupations". Once you exclude non-trade – jobs like "administrative workers" – the annual decline is only 1.9%, not 7.8%.

That decline in trades was also from a relatively high base: between September 2020 and September 2024, the number of in-training trades apprenticeships increased by 29.6%, versus population growth of 6.5%.

Now, Kohler may still be right that Australia needs more trade apprentices, and one way to do that is, as he suggests, through subsidies—whether increasing them for apprenticeships, or lowering them for alternative career paths (e.g. marginal students undertaking questionable degrees at our universities).

But how he's presenting the evidence is misleading at best, and deliberately deceitful at worst. And it's not the first time Kohler has played fast and loose with economic data in an attempt to make some other point.

The Donald-25 mind virus

It has been a bit of a slow news week in Australia with the Easter and ANZAC day public holidays back-to-back. But the opposite has been true in the US, where they don't get even a day off despite the cosy relationship between state and church ("In God We Trust"). And I found a recent opinion piece by historian Niall Ferguson, who only a few months ago was warning that Kamala Harris was the bigger threat to democracy than Donald Trump, fascinating:

"In 2020, Covid-19 spread through the global social networks connected by the world's airports — and permanently altered those networks. Today, Donald-25 is having the same effect on the networks we call supply chains. In 2020, the rest of the world responded to China's pandemic by using fiscal and monetary stimulus to offset the shock. Now, in response to the American mind virus, the rest of the world is forced to do the same. In 2020, the rest of the world recoiled from China: as surveys by Pew showed, its approval rating slumped almost everywhere. The same is happening to the US today.

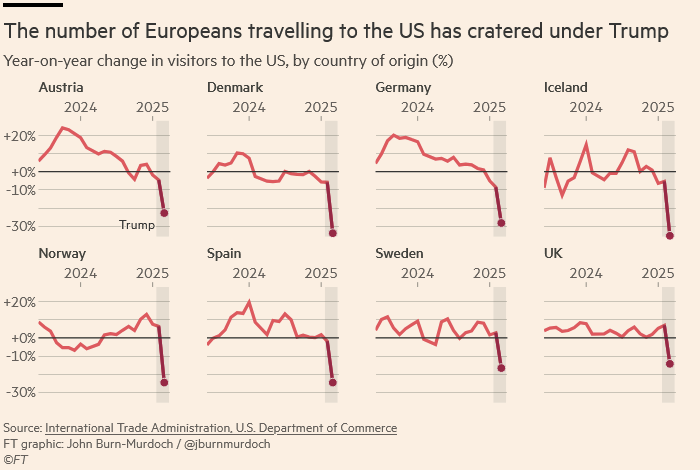

It was last week's travel statistics that first stirred my half-buried memories of Covid. According to the International Trade Administration, the number of visitors from western Europe who stayed at least one night in the US fell by 17 per cent in March compared with a year ago. For some countries, the volume of travel fell by more than a fifth. There has been a surge of flight cancellations by Canadian, French and German travellers. Indeed, Canadian reservations for flights to the US are down 70 per cent."

Here's the data to which he's referring, courtesy of the FT:

After warning that it's likely "only the start of the contagion", Ferguson goes on to lament what could have been:

"As Republicans realise that they risk losing both House and Senate in next year's midterms, their post-election deference to the president will rapidly decay. All this will revive Trump's sworn enemies in the universities, the law schools, the courts and the many government agencies still smarting from the onslaught of Musk's Department of Government Efficiency (Doge). The third attempt to impeach Trump is where the cascade inevitably leads.

It is all such a wasted opportunity. Much of Trump's programme was potentially popular: the crackdown on illegal immigration; the pushback against 'diversity, equity and inclusion' in education; the attempt to reduce bureaucracy and wasteful government spending; the deregulation of the economy. Even a return to the use Trump made of tariffs in his first term — as a negotiating lever, not a revenue source, much less a tool to reindustrialise America via autarky — would have been tolerable."

I'm still hopeful that the Elon Musk-aligned pro-growth (and therefore pro-trade) faction within the Trump administration will win out in the coming weeks or months, as the evidence piles up against the Peter Navarro-aligned pro-tariff faction.

Trump's latest back-down on his China tariffs and walking back of his threats to the Federal Reserve's independence add support to that view, as does the vibe change from pundits such as Michael Pettis, who has swung from an all-in tariff supporter to calling them "reckless" in the span of just four months.

Economists against tariffs

Here's a letter signed by 1,500 economists, including three Nobel laureates (I would have signed but I'm travelling to the US in a couple of months and figured having my name on such a public list may not be wise given recent events):

"The proponents of tariffs portray these measures as acts of ‘economic liberation.’ Instead, tariffs invert the principles of liberty that ushered in an American-led age of human freedom and prosperity.

...

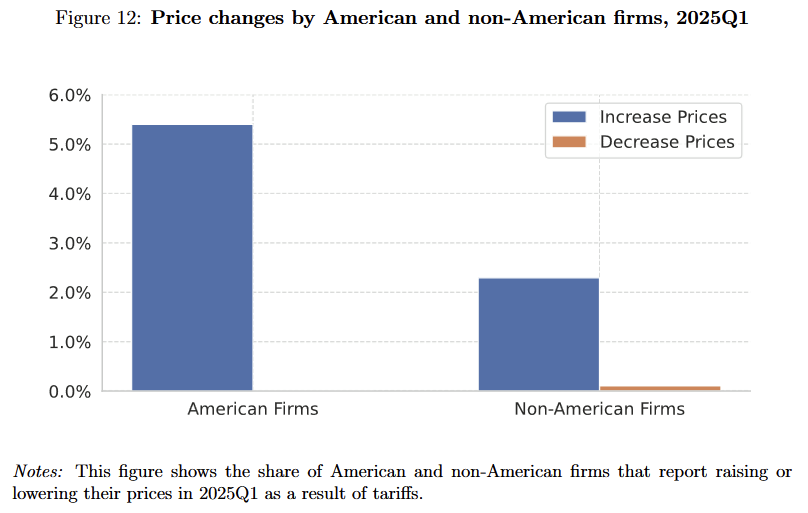

The current administration’s tariffs are motivated by a mistaken understanding of the economic conditions faced by ordinary Americans. We anticipate that American workers will incur the brunt of these misguided policies in the form of increased prices and the risk of a self-inflicted recession."

For the history buffs out there, such petitions don't have a stellar track record at influencing politicians. More than 1,000 economists signed a similar letter protesting the disastrous 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which was passed anyway and made the Great Depression significantly worse that it would have otherwise been.

Further reading

- Yet another paper has found that housing has become less affordable because of "sharply declining productivity in the construction sector, which can help to explain reduced construction rates despite rising prices". It also found that "regulations and the tax system push toward the construction of fewer and larger dwellings", and that to fix it needs "reductions in land use regulation", which will be challenging because of "property owners' incentives to restrict development".

- I've been quite critical of the Trump 2.0 administration, but credit where it's due: "President Donald Trump's April 9 'Executive Order on Reducing Anti-Competitive Regulatory Barriers' has the potential to drive dramatic US economic growth."

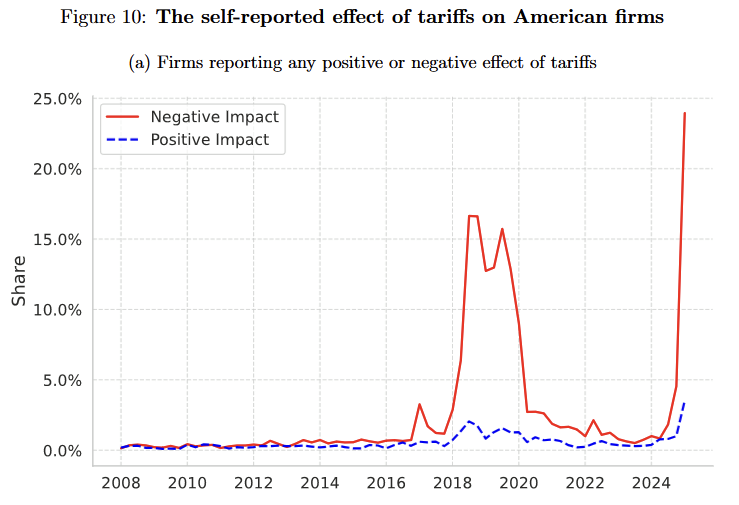

- Geoeconomic pressure: a new, rapidly updated paper from researchers at Columbia, Stanford, and Yale seeks to track how companies are reacting to tariffs, export controls, and financial sanctions. Needless to say, Trump's Liberation Day is taking a toll:

- The world needs less Trump and more Milei: "On trade, Argentines say Trump reminds them more of Milei's nemeses: the left-wing politicians of the Peronist movement—named for the former President Juan Perón—who have long preferred trade barriers... 'The only thing this protection has created is an industrial sector addicted to the state', Milei told manufacturers".

- I don't believe we're ever going to reach artificial general intelligence (AGI) with large language models (LLMs), and people who claim that we will don't understand how the technology works. But even if we did, it wouldn't transform the world overnight: "Social and organisational structures change much more slowly than technology, and technology itself takes time to diffuse. Even if we have AGI today, we have years of trying to figure out how to integrate it into our existing human world."

Have a great long weekend.