The Nobel prize and the gender gap

I’m a bit late to the party but for those still not aware, Harvard’s Claudia Goldin won this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics for her work on women’s labour market outcomes. The Nobel Committee provided a very good press release; a 7-page ‘popular economics’ brief; as well as a much longer advanced report that delves into her scientific contributions more deeply. Do check them out.

One of Goldin’s key contributions is on the gender pay gap. There’s a lot of misinformation in this space – for example, the Albanese government has a commitment to “close the gender pay gap” – a task that, using Goldin’s insights, is unachievable without recognising why the gap exists in the first place. Comparing averages, such as the Minister for Women Katy Gallagher recently did, is at best naive, at worst extremely deceptive:

“[T]here is still plenty of work to do for women whose weekly full-time income is still, on average, $252.30 lower per week than men.”

Goldin showed that there are two kinds of gender gaps, employment and earnings. In Australia, the former has narrowed as participation rates of men and women changed over time: men dropped from a 84.2% participation rate in 1966 to 71.7% today, while women have dramatically increased theirs from 36.6% to 62.5%.

By digging through historical archives, Goldin revealed – contrary to what was popular belief for a long time – that back in the early part of last century women actually had similar rates of workforce participation as they do today. But as the world industrialised and machines replaced the need for farm workers, their participation rates dropped off, presumably because someone had to stay home with the kids. Goldin attributes the modern revival in women’s participation to contraception and various other changes that empowered women, leading to a rise in formal education and employment.

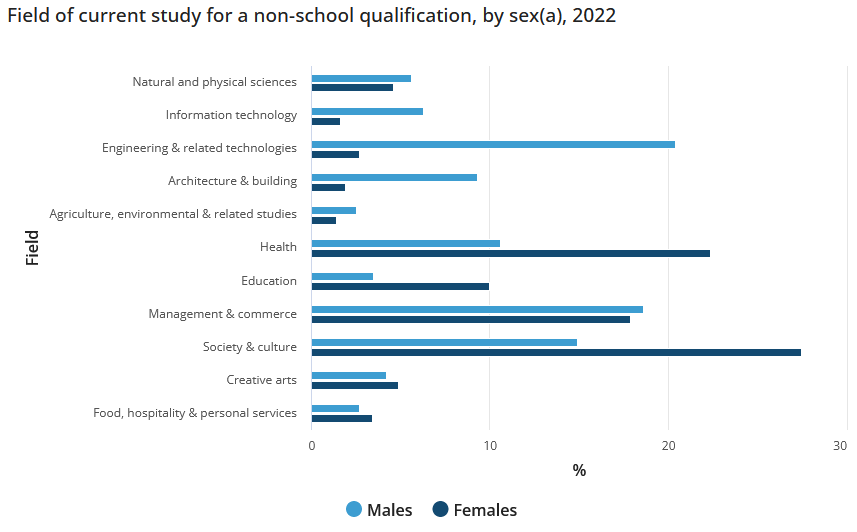

According to Goldin, a large part of the gender earnings gap is explained by two factors. First, women tend to self-select into occupations that are more flexible – while women are more highly educated than men on average, their representation in STEM fields is still very low. It’s also likely to stay low given the distribution of current students, with far more women studying ‘society & culture’ and ‘health’, and more men in ’engineering & related technologies’ and ‘information technology’. The average pay gap that Minister Gallagher wants to close will stay wide open so long as women remain underrepresented in higher-paying STEM occupations.

The second factor that explains the earnings gap is that women have 100% of the children and often raise them too. Goldin’s work shows that around 85% of the gender pay gap can be explained by the ‘parenthood effect’. According to the Nobel Committee:

“They present a framework of compensating differentials, in which women receive a wage penalty for demanding a job flexible enough to be the on-call parent. Men, on the other hand, receive a premium for being flexible enough to be the on-call employee, i.e., constantly available to meet the needs of an employer and/or client. In jobs where such ‘face time’ is valued, one employee cannot easily substitute for another and part-time work is hard to implement. Nonlinearities in wages emerge as a result: workers willing to work many hours are rewarded with a higher wage.”

The Albanese Government’s Workplace Gender Equality Amendment (Closing the Gender Pay Gap) Bill 2023, which focuses heavily on collecting and publishing wage gap data with a next step being the creation of ‘gender equality targets’, looks like it will miss these nuances. While Goldin’s work is understandably light on policy recommendations (there is no easy answer), legislation alone is unlikely to do much to change the gender gap in earnings or occupations. And setting targets could be downright destructive: if the pool of women is smaller than men within certain professions due to choices made much earlier in life, then to achieve equality in outcomes necessitates promoting less experienced women above their more qualified male colleagues. I’m not sure how that might affect organisational performance or morale, and I’m not sure the Albanese Government does either.

While governments are notoriously short-term in their thinking (always the next election), what might be more effective at closing the gap is addressing the prevailing culture of ‘woman stays home with child while man works’. Or variants of it, such as women disproportionately choosing more ‘flexible’ career paths due to being the ‘on-call’ parent. Assuming, of course, that’s what people actually want: who am I to say?

Member discussion