Brisbane should sprint from the Olympics

There's a famous satirical poem by Juvenal mocking the demise of the Roman Empire, lamenting the fact that its populace was no longer concerned with good governance but only "bread and circuses", i.e. for distractions and the satisfaction of their most immediate desires:

"...if the old Emperor had been surreptitiously

Smothered; that same crowd in a moment would have hailed

Their new Augustus. They shed their sense of responsibility

Long ago, when they lost their votes, and the bribes; the mob

That used to grant power, high office, the legions, everything,

Curtails its desires, and reveals its anxiety for two things only,

Bread and circuses."

In modern parlance, the equivalent might be the constant stream of debt-financed handouts our governments bequeath us, instead of good governance and structural reform that will improve our lot in the long run. Throw in a couple of new stadiums (looking at you, Tassie) and in the case of Brisbane, an Olympic Games, and we have our very own cycle of bread and circuses.

Brisbane's circus

A legacy of former Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk – who also bequeathed herself the new title of Minister for the Olympic and Paralympic Games – Brisbane was elected as the host of the 2032 Summer Olympics on 21 July 2021, beating out... no one.

That's right: Brisbane was the only candidate, supposedly because the International Olympic Committee (IOC) had shifted to a model that gave it "more control in dealing discreetly with preferred candidates and removed the risk of vote-buying".

Vote-buying, also known as corruption, has been a feature of organisations such as the IOC for about as long as they have existed. Why would anyone buy votes to host the Olympics, you ask? Because of what's known as "Sportswashing", a term coined after Azerbaijan's hosting of the 2015 European Games. Sportswashing is essentially when dodgy regimes use sport – circuses – to distract their people and the world from the various scandals and human rights atrocities they may or may not have committed. Notable examples include the Sochi Winter Olympics, Beijing Olympics (summer and winter), and most recently the FIFA World Cup in Qatar.

Saudi Arabia, with all of its recent and not-so-recent controversies, is becoming an excellent sportswasher, all under the guise of diversifying its economy:

"Saudi Arabia has spent at least $6.3bn in sports deals since early 2021, more than quadruple the previous amount spent over a six-year period, in what critics have labelled an effort to distract from its human rights record."

Countries such as Saudi Arabia don't mind paying the price of hosting an Olympics or World Cup because it is the perfect circus: see, World, we're not some backwards, repressive regime but a wealthy, healthy modern democracy, just like you!

But back in Queensland, Annastacia Palaszczuk had no such motivation. Despite what you might have heard, Brisbane isn't all that bad; certainly not bad enough to justify sportswashing, anyway. According to Palaszczuk, the reason she wanted Brisbane to host the Olympics was because:

"We want to show the world that mid-sized cities and regions can host the Games without financial distress or missed deadlines."

Has that claim ever aged like milk: less than a year later, the state government's Coaldrake review found the Queensland government had created "a culture that, from the top down, is not meeting public expectations", where "public servants have become fearful of providing frank and fearless advice to government".

Add to that "allegations of a partisan Crime and Corruption Commission... of too-cosy relationships with lobbyists, and alleged interference in the work of the integrity commissioner", along with an ill-timed overseas holiday and poor approval ratings, and Palaszczuk was eventually forced to resign from politics entirely.

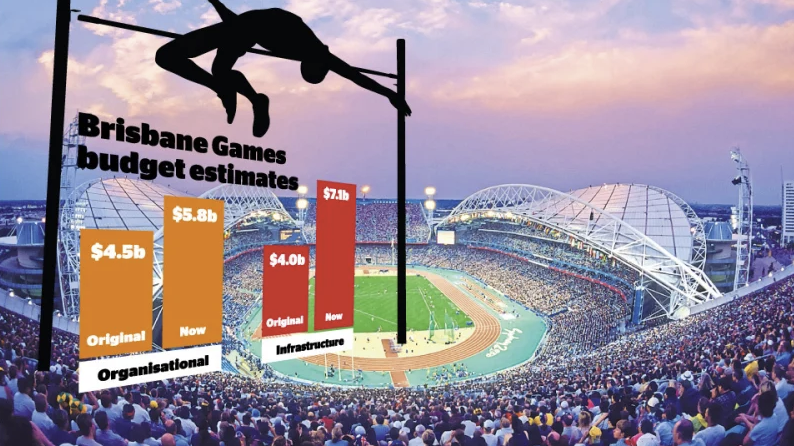

As for her pet project, the Olympics, it quickly became mired in financial distress and missed deadlines – exactly what Palaszczuk claimed she wanted to avoid. Perhaps the worst example was the proposed rebuild of the 42,000-seat Gabba, the cost of which blew out from an initial $1 billion in 2021 to a whopping $2.7 billion just two years later, "in part because the state government rushed its original cost estimate".

Then earlier this month, new Premier Steven Miles scrapped it entirely:

"The previously proposed re-build of the Gabba will not proceed, instead replaced with a more modest enhancement of the existing facility in consultation with AFL, Cricket Australia, and other stakeholders."

For now, the Brisbane Olympics will still go ahead in 2032, with no fewer than eighteen facilities needing to be upgraded or built (not including temporary venues or athlete villages) to ensure the city meets the IOC's strict standards.

But it really shouldn't.

Brisbane should never have bid for the Olympics

What's interesting about the Olympics is that hosting it is almost universally condemned in the economics literature. Sure, the host city gets several weeks of excitement accompanied by a stream of consultancy reports on "economic impacts" that aren't worth the paper they're printed on, but that's inevitably followed by at least as many years of economic costs.

Premier Steven Miles may have saved his state some money by refusing to upgrade the Gabba but his solution to move the athletics event to the dilapidated Queensland Sport and Athletics Centre at a cost of $1.6 billion, and upgrade the rectangular Suncorp Stadium for $500 million, wasn't much better.

Perhaps not seeing the irony, the 40,000-seat Athletics Centre – surrounded by zero public transport – was built for the 1982 Commonwealth Games, and has remained unloved and underused ever since. It will almost certainty meet the same fate following the 2032 Olympics.

As for the Suncorp upgrade, it's actually one of the more-used stadiums in Queensland, being home to Brisbane Broncos and Redcliffe Dolphins (NRL), Brisbane Roar A-League team, Queensland Reds rugby team along with various one-offs such as the State of Origin and international sport and music events.

But that just further begs the question: why is the taxpayer forking out the full cost of an upgrade to something with commercial appeal? Imagine if Qantas approached the Queensland government and said "yo we need some upgrades to our A330 fleet. You'll pay for it all but we'll keep the usage rights and revenue. Just think of all the jobs and economic activity it'll generate!"

Any normal person would, rightly, protest loudly against such a move. But that's basically what governments do for sport stadiums. Rather than the chief beneficiaries such as the AFL or NRL paying for them, taxpayers do under the guise of broader economic impacts. But as economists John Siegfried and Andrew Zimbalist wrote, there is very little payoff for the city:

"Few fields of empirical economic research offer virtual unanimity of findings. Yet, independent work on the economic impact of stadiums and arenas has uniformly found that there is no statistically significant positive correlation between sports facility construction and economic development."

By agreeing to host the Olympics in Brisbane, the government has decided to spend billions of dollars on stadiums and other facilities instead of other programs, like healthcare or housing. Many of those facilities will struggle to find a use after the Olympics, and those that do will benefit their tenants and the relatively small number of people who attend events, not the average Brisbanite.

And even then, adding capacity to Brisbane's existing stadiums makes very little sense. The Gabba, for example, averages ~15–30,000 people at AFL games depending on how well the Lions are going, well below its 42,000 capacity. But even if it were full every week, a better option would be to raise prices. According to the book Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums:

"To begin, in responding to demand a team usually can do almost as

well by increasing ticket prices as by increasing the number of tickets

sold. Studies of the market for sporting events typically find that the

demand elasticity is close to 1, so that revenues from the sale of tickets—

ticket price times attendance—do not exhibit a great deal of variance

with respect to changes in ticket prices."

The higher ticket prices go, the better the business case for an upgrade. Either way, there's no economic case for taxpayers to be subsidising such decisions.

If it's that bad, why on Earth did Brisbane bid for the Olympics?

In economics there's a phenomenon called the agency problem. Essentially, when there's a misalignment of interest between the people who make a decision and those who pay for the decision, you can get some very perverse outcomes. In this case, Palaszczuk gained the most from hosting. Think overseas trips, such as a VIP visit to Tokyo while Queenslanders were locked in during the pandemic, ribbon cutting ceremonies for new facilities, or being able to boast about her 'legacy'. Here's what Anthony Albanese said after he was informed of Palaszczuk's "decision to resign as Premier of Queensland":

"When the world turns its eyes to the 2032 Brisbane Olympics, so much of what they see in that vibrant and prosperous setting will reflect the vision and ambition of Annastacia Palaszczuk."

According to the book Circus Maximus: The Economic Gamble Behind Hosting the Olympics and the World Cup, when you have both imperfect information and a principal-agent problem – that is, a host city that does not fully know what the potential benefits and costs might turn out to be, and where the interests of the people doing the bidding (the agents) "are not coincident with those of the host country's or city's population (the principal)":

"The expected outcome is substantial financial and overall losses, which will only be exacerbated by cost overruns."

Sound familiar? It should, given that's exactly what's playing out in Brisbane today, a full eight years before it's even due to host the Olympics.

According to economist Paul Oyer, it was all entirely predictable:

"The common thread in each of these and countless other examples is that individuals had the power to decide how a much larger group of people spent their money. This misalignment of interests led to an elected or self-declared leader making financial decisions that hurt constituents while making himself or herself better off."

Palaszczuk has paid no personal price for condemning Brisbane to hosting the Olympics. But unless a future leader pulls the plug, the people of Queensland (and the rest of Australia, given the Commonwealth is chipping in a decent chunk) will still be paying for decades to come.

There's still time to run away

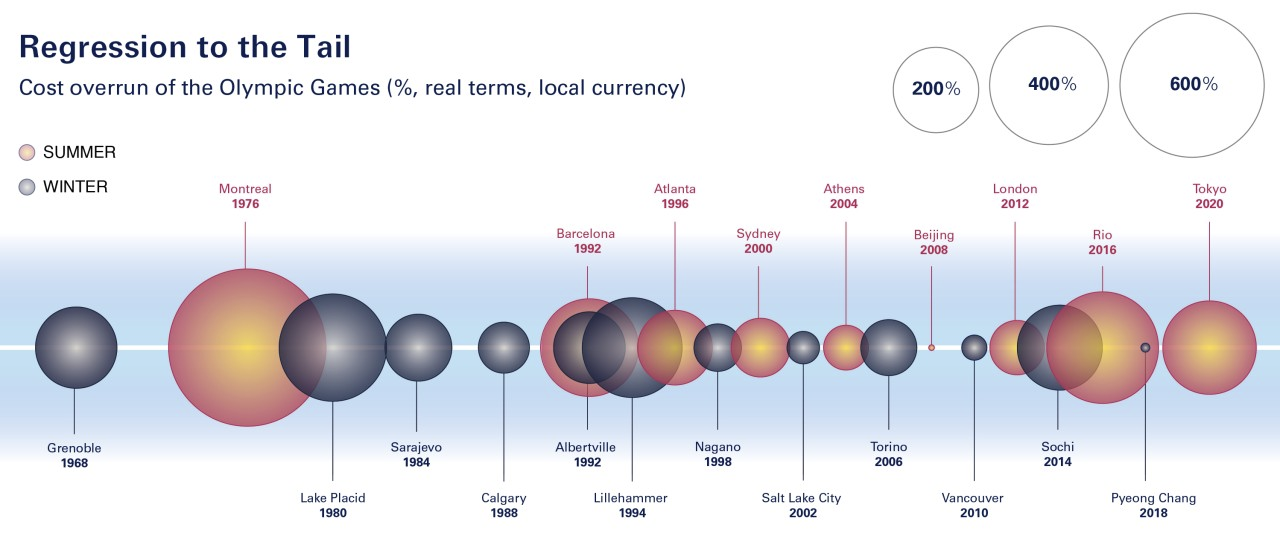

The only city to cancel an Olympic games after winning the right to host them was Denver in 1972. It turns out that lock-in is very real, which is one reason why Olympic cost overruns average 172%: hosts feel obliged to "throw good money after bad".

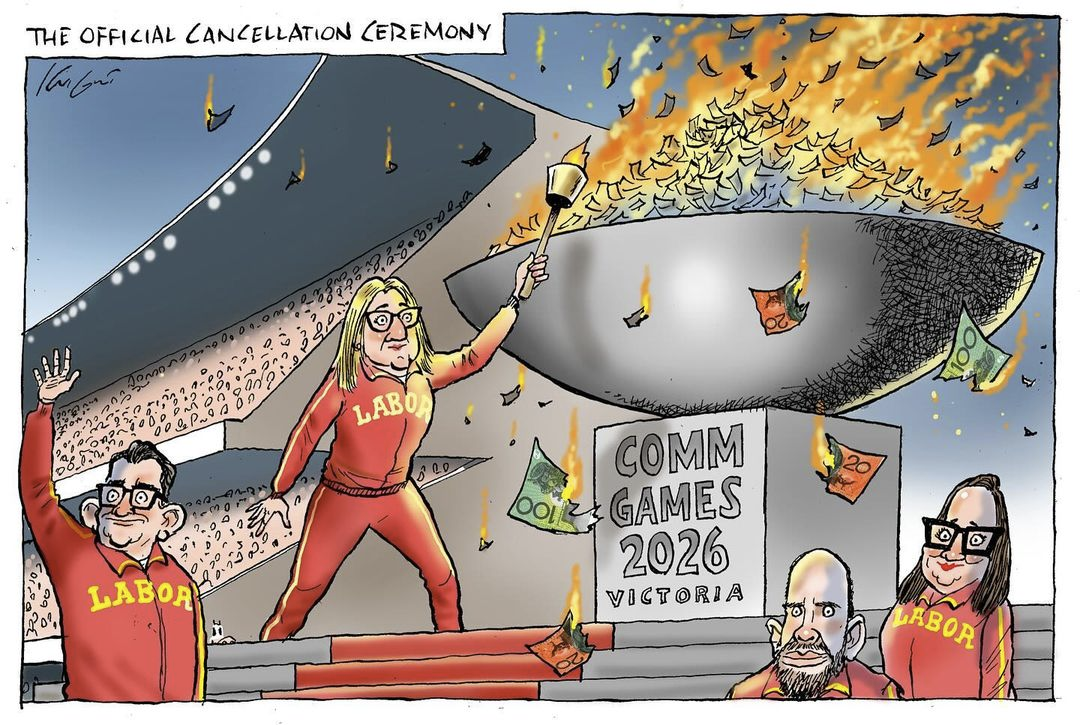

Thankfully we have an even more recent, local precedent of cancelled sporting events. You might recall that Victoria cancelled the Commonwealth Games in July last year, which has now been revealed to have cost the state more than $589 million. Cartoonists had a field day, with gems such as this from Mark Knight:

But you have to remember that the money was already gone. There was no salvaging it; the choice was either to waste even more money by continuing on with the Games, or admitting the mistake and committing to stop the bleeding.

We economists call this the sunk cost fallacy, where people focus on what they can't change instead of what they can change. In the case of the Olympics, Premier Steven Miles can't undo what Palaszczuk has already spent on agreeing to host the games: that cost cannot be recovered; it's sunk. But he can admit that his government made a mistake and avoid throwing even more good money and time after bad.

And there's still a lot of money that needs to be spent to get Brisbane ready for the Olympics – likely tens of billions of dollars. But a growing city like Brisbane would be better off if the government spent that on something else, such as upgrading its transport network, helping to retrain workers who lose their jobs to AI, or improving its health system, all of which will have longer-lasting benefits than the Olympics.

It's not too late to save billions of dollars. But to do so, Brisbane will have to – and should – withdraw as host of the 2032 Olympics.

Member discussion