Husic is right about the corporate tax

A few weeks ago, the federal Minister for Industry and Science, Ed Husic, ruffled more than a few feathers by telling the audience at an AI summit that Australia could do with some corporate tax reform:

"We need to see business be able to invest and to free up capital to do that [raise manufacturing capital]. And if they're committed to do that, then be able to see that enabled, but having done that too in a way where we see people's wages and their security or employment improve. And that is going to be the test. Any discussion around corporate tax reform needs to be able to entwine both the benefits for capital and for labour; to be able to have that successful discussion. I think that's where we probably will be likely to head.

But I'll be very careful about how much I say if you don't mind because I’ve got a cabinet colleague in the form of the Treasurer who manages the tax revenues, and so I think I might try and get the balance right, if you don't mind."

There was nothing in Husic's formal address about corporate taxes, suggesting that he went off script and told us what he really thinks, rather than simply rehashing the party line – some of you might remember that in 2018, Labor blocked the Turnbull government's attempt at cutting company tax rates for larger companies to 25% (which isn't tax reform, but I'll get to that in a bit).

Treasurer Jim Chalmers, on whose toes Husic was stepping, was quick to deflect attention by saying that the comments were "entirely consistent with the sorts of things we have been saying for some time":

"A large proportion—indeed, most—of the $23 billion of the Future Made in Australia package that I announced from this dispatch box almost exactly two weeks ago was about company tax reform in the form of production tax credits. In addition to that—and here I pay tribute to the small business minister—we're also extending the instant asset write-off for small business, also in the company tax system."

Now, there's a big difference between tax credits and asset write-offs, and the kind of corporate tax reform to which Husic was alluding. Chalmers is conflating the two, but reform entails meaningful change to how we collect taxes, whereas credits and write-offs are temporary measures that might actually come at the cost of future reform. As the Grattan Institute observed:

"[T]ax cuts without reform leave less money to buy genuine tax reform, reducing the government's room to respond to future economic shocks, and pushing the cost of today's spending onto future generations.

Real tax reform isn't easy, but neither is good government."

I don't know for certain whether Husic wants genuine corporate tax reform, or some version of Chalmers' misstatement of reform, but from herein I'm going to take him at his word – that he wants actual reform. And if so, he has a very, very good point: the corporate tax is one of our most inefficient, welfare-harmful taxes and should be reformed.

The incidence of corporate taxes

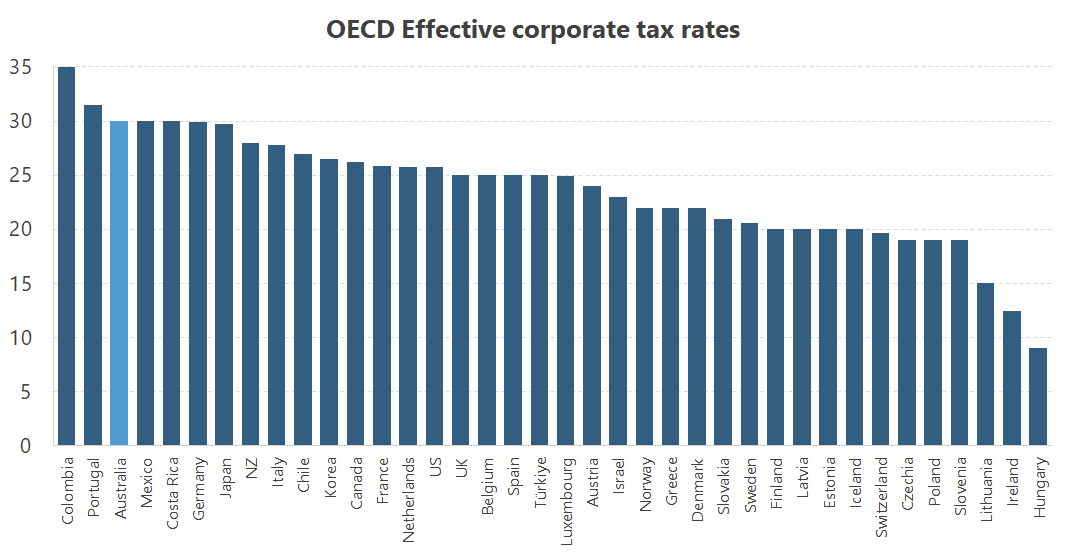

Australia has the highest corporate tax rate in the OECD, after Colombia and Portugal.

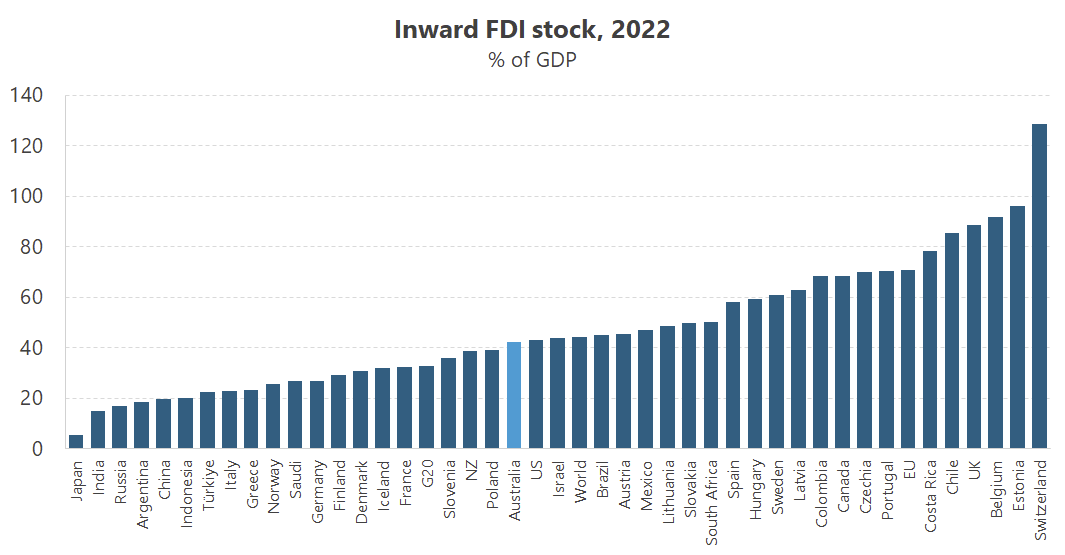

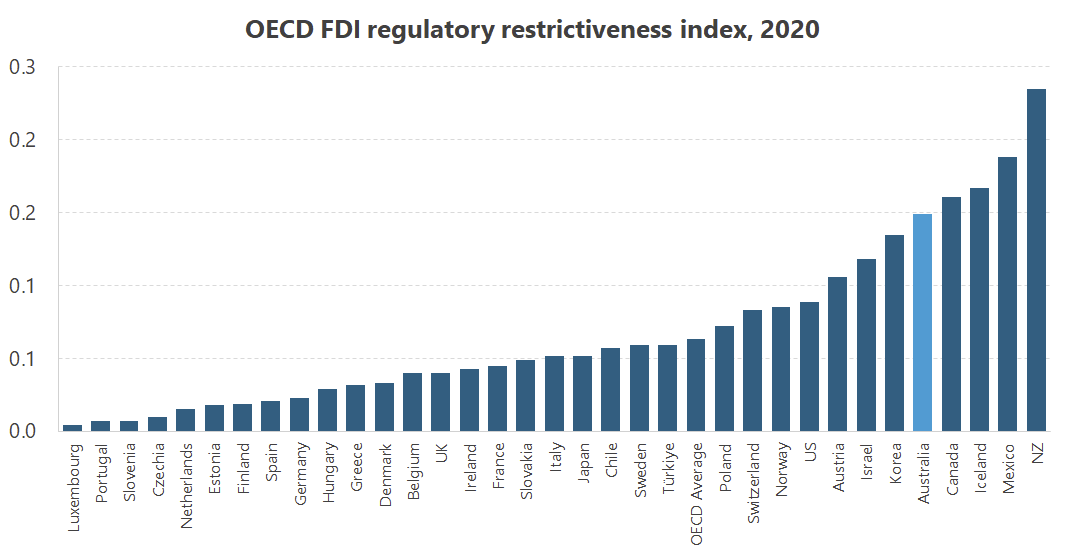

We also have a relatively low stock of inward foreign investment, and our regulatory regime doesn't exactly welcome foreign investment with open arms.

It's absolutely true that if we cut corporate tax rates tomorrow, the owners (shareholders) of profitable businesses will benefit. And because of Australia's dividend imputation system that is only available to residents, many of them would be foreigners.

But that's not the whole story.

Economic theory tells us that the corporate tax must be paid for by consumers (higher prices), workers (lower wages), or owners (lower profits). Empirical studies back that up, and also tell us that in Australia up to two thirds of the corporate tax may be borne by workers, primary through lower real wages. Overseas studies suggest workers and consumers pay around 30-50% of it.

A study that looked at Australian manufacturing, the sector so dear to Husic, found because of "significant forward shifting of the tax onto consumers in the form of higher product prices... the corporate income tax resembles a general sales tax that is regressive as to income".

So it's a regressive tax that harms the lowest-earning Australians, is primarily borne by workers through lower labour productivity, and is our second most inefficient tax (i.e., growth and productivity sapping) behind stamp duty. It also incentivises companies to load up on debt instead of equity because interest expenses can be deducted, distorting firms' investment decisions and elevating risk.

Getting rid of the corporate tax would raise the return to capital, increasing the incentive to invest. As investment grows, returns fall and some of those gains must flow elsewhere – namely to workers, which are what makes capital productive. More investment means more demand for workers, higher productivity, higher wages, and lower prices.

ANU's Tax and Transfer Institute director Bob Breunig said that even a simple cut to Australia's corporate tax rate would be worthwhile:

"The evidence and the theory is good for workers: that cutting the corporate tax rate creates more jobs, creates more productivity, and creates higher wages. The evidence is really strong that it also increases investment. The estimate from Europe is that a 1 per cent cut leads to 4 per cent additional investment."

Work by one of the world's most influential economists, Boston University's Laurence Kotlikoff, found that even if abolishing the corporate tax would force the government to raise taxes elsewhere, the benefits are enough to do it anyway:

"...are large enough to produce a Pareto improvement, with modest welfare gains accruing to early generations, both skilled and unskilled, and very sizable welfare gains experienced by young and future generations, both skilled and unskilled. Importantly, this result arises naturally with no special compensation mechanism required to transfer from winners to losers."

There are much better options out there to finance government than the corporate tax. So why the hell does it persist?

Taxing the golden geese

The corporate tax is a very tricky beast to slay in Australia because of the political incentives at play. Here's the rub, from Chalmers himself:

"I don't have an ideological aversion to changing headline company tax rates but it's not something that the budget can afford right now."

Chalmers was a staffer to former Treasurer Wayne Swan, who presided over the ill-fated decision to ignore 128 of the 138 recommendations handed to him in a report he commissioned from former Treasury secretary, Ken Henry. Instead, the major tax move made by the Kevin Rudd/Wayne Swan government wasn't even suggested by the review, and the decision to impose a super profits tax on big miners without any changes elsewhere, because "the government couldn't afford it", went down like a lead balloon with the electorate.

But the need for corporate tax reform will only get stronger. According to Henry, Australia's governments are "too reliant on economically damaging taxes on wages, corporate non-mining profits, and state property stamp duties":

"Dr Henry said business investment for years had been at 'terribly, terribly low' recessionary levels, as Australia was one of the very few advanced economies not to cut its 30 per cent corporate tax rate this century.

It explained why Australia had become a net exporter of capital because local investment was less attractive, he said."

If Chalmers is still reading from the Swan play-book, which he certainly appears to be, then corporate tax reform is simply "too costly". And if that was all he did, it would be costly for his spending ambitions, no doubt – but the cost to the country of not reforming is much greater.

Australia's politicians are essentially stuck in a trap. They're addicted to the corporate tax, which is the federal government's second-largest source of revenue. Half of that tax comes from just 11 companies in mining and banking. They are our proverbial golden geese, and without passing new laws, the corporate tax is the primary mechanism through which the federal government is able to capture its share of the rents (royalties can only be levied by states).

Rudd and Swan tried to change that but they fumbled it worse than Herschelle Gibbs at the 1999 Cricket World Cup, effectively killing off any chance of reform for a generation. As Swan's staffer, Chalmers must have been involved in that process; so no matter how much sense it makes for the country, it will probably have to wait until someone other than Chalmers – perhaps even Husic – holds the Treasury portfolio.

That will eventually happen because it has to: as Henry noted, at some point "the intergenerational social compact must surely fracture", because "in stark contrast to the post-war period, because of population aging, a shrinking proportion of the population, made up of relatively young workers, will have to shoulder a rapidly accelerating share of the burden of financing government".

What's needed is a way to continue taxing the golden geese, many of which are in the business of digging up finite resources and who have few other options but to do business in Australia, while also eliminating inefficient taxes, such as the corporate tax, that will attract capital and encourage new industries to set up shop in Australia.

A workable path forward

The most efficient way to replace any lost corporate tax revenue would be through spending cuts and a higher GST (with the current exemptions removed). There's a large body of literature that shows taxing consumption is preferred to taxing income, especially capital income.

As the now-head of the Productivity Commission, Danielle Wood, wrote in a report last year, raising the GST to 15% and removing the exceptions while providing additional transfers to low-income households with few assets would raise around $12 billion annually for the federal and state/territory governments to share.

As part of the deal, the states could be persuaded to use their share of the additional revenue to cut stamp duties, which are volatile and highly inefficient.

But such a tax shift might be politically difficult given it would require cooperation between all levels of government, and our states love nothing more than bickering about the current GST distribution. Then again, perhaps precisely because our states are so unhappy with the current system, the federal government could offer them the carrot of fixing it in exchange for a higher rate, some of which will flow to Canberra? I don't know, but it's certainty a question worth asking.

Yes, a higher GST will mean that the Boomers spending it big while younger folks suffer through higher rents and mortgage payments will pay a bit more tax. But I don't think too many people would object to that, given that they've had a pretty damn good ride.

In addition to raising the GST, some of the lost corporate tax revenue could be recovered by reforming the tax itself prior to a complete phase-out. ANU's Kristen Sobeck and her colleagues have already given them the model, replacing the corporate tax "with one built around an Allowance for Corporate Equity (ACE)":

"It would tax company income only after deducting an allowance for a reasonable rate of return on the capital invested.

This means it would tax some companies barely at all – those that made only a reasonable rate of return on the capital invested.

It would tax other companies – those that make returns that exceed a reasonable rate – more highly."

In other words, the ACE would get rid of the incentive to load up on debt, wouldn't tax the majority of companies all that much, but would still allow the government to tap its golden geese.

The only thing we're missing is the political willpower to actually do it.

Member discussion