It's a good thing we don't make cars any more

Chinese cars offer great value and affordability, but US automakers are lobbying for protection, just as they did with Japan in 70s. Fortunately, Australia's lack of auto manufacturing means that this time around, we can enjoy the full benefits of competition!

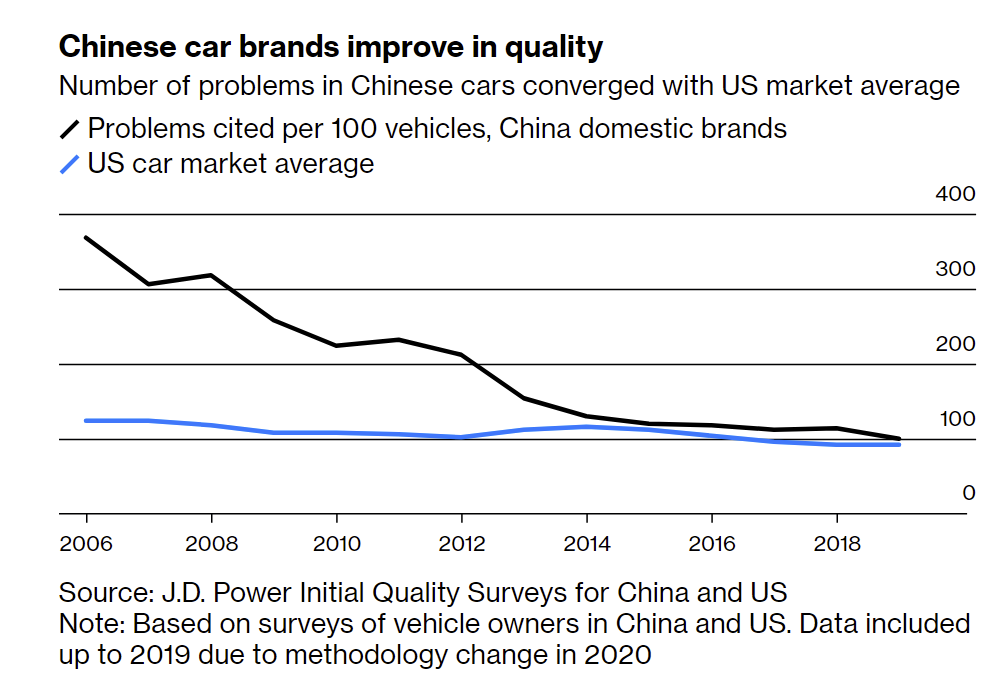

Several years ago, when I would think of Chinese cars the word quality would never be close to the top of the list of adjectives I'd use to describe them, unless it was prefixed with poor. But if you've been to China recently, or driven in one of the newer models that are now in Australia, you'll quickly change your mind: these days they're more similar to Japanese cars than the breakdown-prone versions we used to see. And the data back this up, with Chinese cars now comparable with those made in the US in terms of reliability:

China now produces high quality cars, which is a huge win for Australian consumers: given we have no tariffs on Chinese cars thanks to the ChAFTA trade agreement, China is another big market – adding to Japan, Korea, Germany and the US (noting that many are actually assembled in Thailand) – from which we can source vehicles at competitive prices.

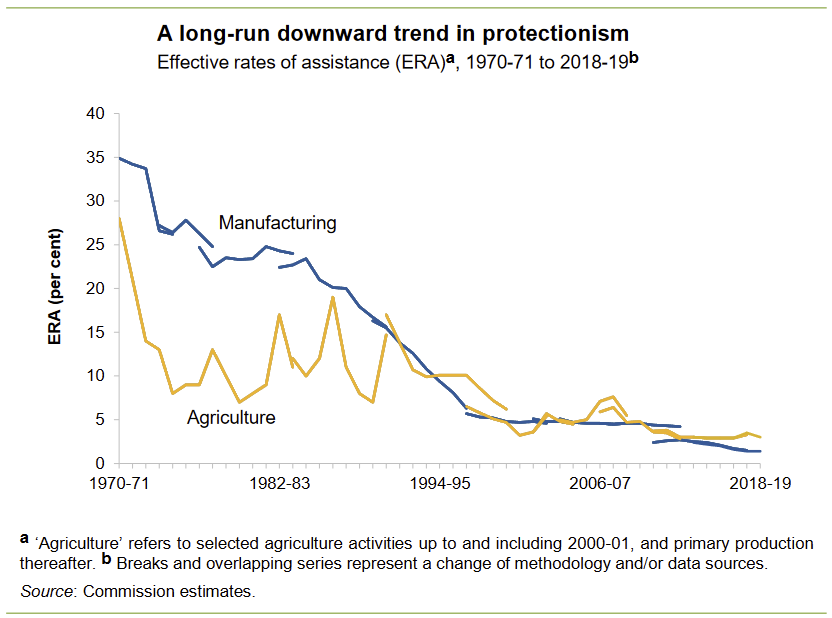

But in a different timeline, we may never have got here. I'm certain that if we still manufactured cars in Australia, then allowing affordable Chinese imports to be sold here would have been politically intolerable. That's because before it went extinct, our auto manufacturing industry was historically "one of the most heavily assisted industries in the country", with a rate of assistance in 2011-12 equalling nearly 10% of the industry's value add – higher than any other industry in Australia:

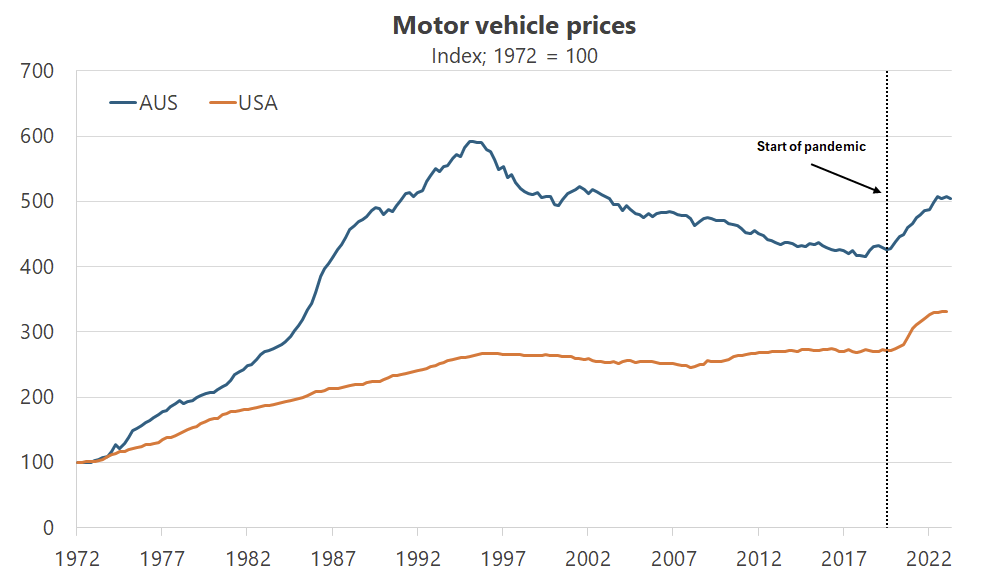

Thankfully from a consumer's perspective, a gradual reduction in government protection caused producers to finally stop making cars at the end of 2017, with most of the estimated 40,000 people who lost their jobs managing to find more productive employment elsewhere (Australia's unemployment rate has trended lower ever since). The credible reduction in protectionism flowing from the reforms of the 1980s, combined with an influx of excellent, affordable cars from overseas, helped reduce vehicle prices for Australian consumers for the first time in decades:

Consumers in the US were not so fortunate. While their automotive sector was considerably more productive than Australia's, so vehicles over there were always relatively cheap, to this day the industry still receives government protection from foreign competitors.

Protectionism vs the consumer

Most recently, US automakers have been insulated from the threat of Chinese cars thanks to a 27.5% tariff that former President Donald Trump slapped on them, at considerable cost to American consumers and importers. President Joe Biden – supposedly from the more trade-friendly Democratic party – has not meaningfully lowered any of those tariffs, perhaps because despite the poor economics, car tariffs are electorally popular.

Needless to say, Chinese cars have faced challenges in gaining market share in the US. Not to be deterred, the world's largest EV manufacturer, China's BYD, is trying to change that by opening a facility in Mexico, exploiting a loophole that makes its cars assembled there exempt thanks to the USMCA free trade agreement (formerly NAFTA). If it succeeds then Chinese-made electric vehicles will, to quote the NYT, "hit Detroit like a wrecking ball".

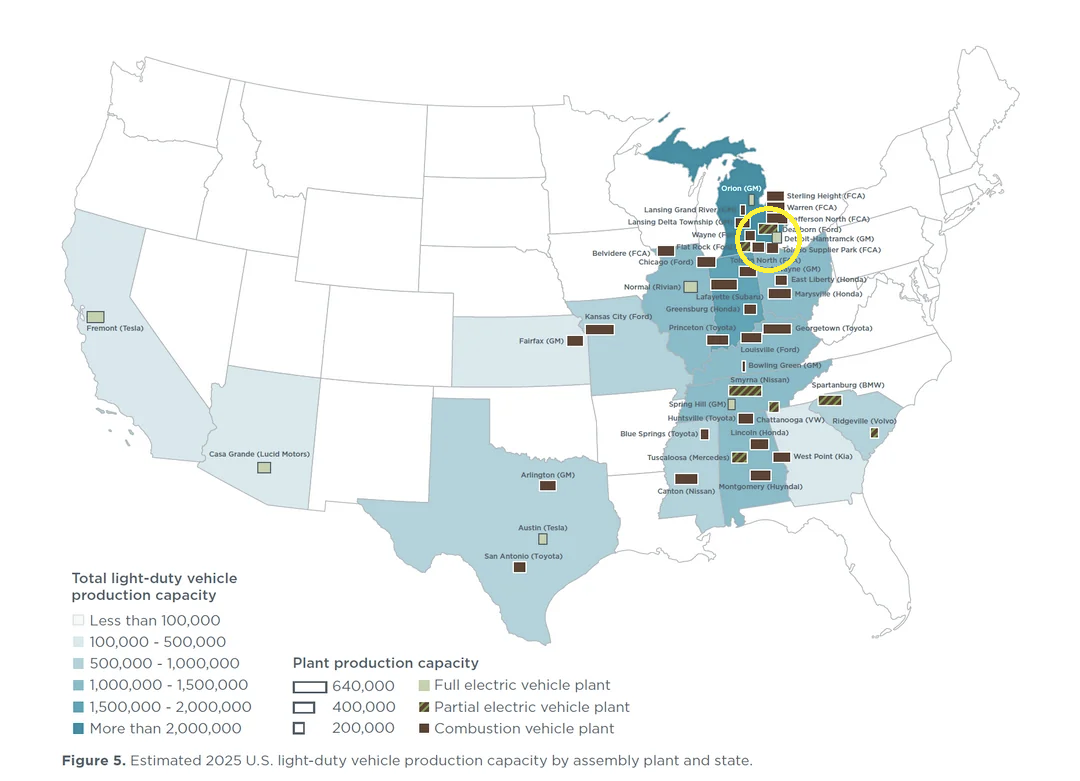

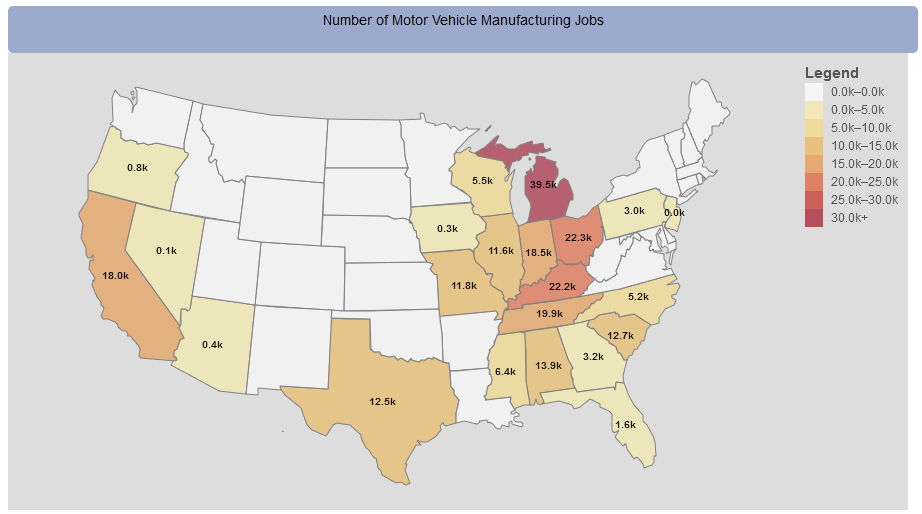

Why Detroit? It's the heart of car manufacturing and assembly in the US:

In response, President Biden has accused Chinese car manufacturers of being a danger to "national security" (an old protectionist trick), threatening Chinese vehicles with new regulations or restrictions "because their operating systems could send sensitive information to Beijing".

But while Biden chose the indirect route, senate Republicans were far less opaque in their attacks on Chinese automakers, demanding that the tariff on Chinese imports is raised even further – to 125% – and for it to include vehicles assembled in Mexico, due to "the existential threat posed by China".

Those comments, plus what we know about Trump, means I can almost guarantee that Chinese vehicles will not be able to achieve significant market share in the US market – at least not until after the next Biden/Trump Presidency – despite the clear benefits to consumers.

After all, this isn't the first time the American auto industry has struggled to adapt to changing consumer preferences, having relied on several government bailouts and protectionist measures to sustain itself in the past. Auto manufacturers are the favourite child of American politicians on the left and right, because it's a big employer of a concentrated group of voters in key swing states (won by less than three points), such as Michigan.

While concerns over national security risks cannot be entirely dismissed, us economists like to look at the incentives: if Chinese cars were ever caught spying on their occupants they would promptly be banned worldwide, bankrupting their auto industry overnight. There's no reason why the same forces that keep the hundreds of millions of Chinese-made smartphones, laptops, tablets, PCs and TVs from spying on us won't also apply to Chinese-made vehicles (the same cannot be said for certain software, such as TikTok).

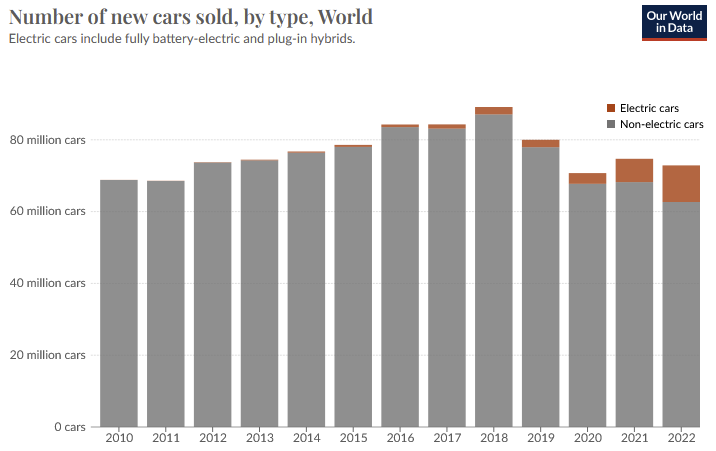

But Chinese cars do threaten Biden's attempt at reviving industrial policy, aka the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which isn't going all that well:

"Mathias Miedreich, chief executive of Umicore, said sales of Chinese electric cars were surging in contrast to the US due to better performance and affordability. 'They are simply good cars and people buy them. The American ones [producers] seem to struggle to bring good electric vehicles [to market]'.

...

Miedreich's comments also add to growing scepticism over whether the IRA, President Joe Biden's flagship climate change programme, has accelerated demand for EVs as much as expected. 'The end market stimulation through the $7,500 [tax credit] was probably not enough because what was forgotten is you still need good products', the Umicore boss said."

Politically, causes such as the environment will always take a backseat to labour interests but especially to a politician's hopes of re-election; it's why Albanese and Bowen spend about as much time talking about "good, green jobs" as they do renewable energy. But they are two separate things, and if your renewable energy policy also includes a jobs or 'buy local' requirement, then you're going to end up with sub-par policy and poor outcomes for both the environment and jobs.

China as the new Japan

How has China dominated? It's quite simple, really – it makes good cars that people want to drive at lower prices than its competitors:

"The biggest threat to the Big Three [Ford, GM and Stellantis] comes from a new crop of Chinese automakers, especially BYD, which specialize in producing plug-in hybrid and fully electric vehicles. BYD's growth is astounding: It sold three million electrified vehicles last year, more than any other company, and it now has enough production capacity in China to manufacture four million cars a year. But that isn’t enough: It's building factories in Brazil, Thailand, Hungary and Uzbekistan, to produce even more cars, and it may soon add Indonesia and Mexico to that list. A deluge of electric vehicles is coming.

BYD's cars deliver great value at prices that beat anything coming out of the West. This month BYD unveiled a plug-in hybrid that gets decent all-electric range and will retail for just over $11,000. How can it do that? Like other Chinese manufacturers, BYD benefits from its home country's lower labor costs, but this explains only some of its success. The fact is that BYD and other Chinese automakers like Geely, which owns Volvo Cars and Polestar brands, are very good at making cars. They have leveraged China's dominance of the battery industry and automated production lines to create a juggernaut."

The article fails to mention that BYD and other Chinese automakers have also benefited from significant government subsidies and investment in EV research and development, allowing them to rapidly scale up production and innovate battery technologies.

Nevertheless, China isn't just imitating these days; it's also innovating. For example, BYD commercialised the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery technology now used in its cars, which it calls "Blade", allowing for cheaper, faster charging battery-powered vehicles that no longer catch on fire. Tesla, Kia, Hyundai, and Toyota now use BYD's Blade batteries in their vehicles, with the head of Ford's EV unit saying BYD's success meant it had better "get going on EVs, or we don't have a future as a company".

History repeating

This is the same pattern that occurred when Japan's Toyota, followed by a flurry of automakers across the region, revolutionised the auto-making industry in the 1970s (e.g. with the Toyota Production System), raising productivity and out-competing their US rivals. The similarities between 1970s Japan and 2020s China are uncanny, although China today faces a potentially harsher response due to the relatively stronger geopolitical tensions between the two countries:

"The number-three car maker, Chrysler, almost failed and only survived as a result of government assistance. As many as 650,000 workers were out of jobs in auto-related industries in 1979. Faced with this difficult situation, the UAW [United Auto Workers] conducted a strong campaign for trade restrictions and for investment in the United States by Japanese automobile producers... The automobile issue became emotional and hysterical in the United States, and the expression 'Japan bashing' was frequently used and reported in the Japanese media. This flaring up of the automobile issue was partly due to the Presidential race in 1980."

After failing to persuade the International Trade Commission, which ruled that US automakers were struggling more from "high interest rates, the recession, and a change in consumer demand" than from Japanese imports, the US and Japanese governments agreed to an import quota. The result was that Japanese automakers shifted their exports to higher priced vehicles, depriving US consumers of affordable, low-end cars. According to Shujiro Urata writing in the Asian Economic Policy Review, the quota:

"...relieved the industry/labor from adjustment, and thus provided benefits in the short run, but it incurred costs by delaying the necessary adjustment for achieving economic growth in the long run... The biggest losers were the US consumers because the VER [voluntary export restraint] forced them to pay high prices and narrowed their product choices."

Urata cites estimates of the welfare costs showing that producers gained about half what consumers lost, with the cost per job saved around four times the US median income at the time. Concentrated benefits and dispersed costs – music to a politician's ears, costs be damned!

In a sense, the Chinese car industry today is where Japan's was in the late 1970s. We're in a cost of living crisis with relatively (for modern times) high interest rates and slow real per capita economic growth. China's BYD can now produce a plug-in hybrid car "at just over US$11,000" – less than half what Ford lost on every EV it sold in 2023 – a boon for consumers for whom price has been a key impediment to buying an EV.

Consumer preferences are shifting to more economical EVs, while US automakers are stuck in the past, "selling pickup trucks, SUVs and crossovers to affluent North Americans":

"In other words, if Americans' appetite for trucks and SUVs falters, then Ford and GM will be in real trouble. That creates a strategic quandary for them. In the coming years, these companies must cross a bridge from one business model to another: They must use their robust truck and SUV earnings to subsidise their growing electric vehicle business and learn how to make EVs profitably. If they can make it across this bridge quickly, they will survive. But if their SUV profits crumble before their EV business is ready, they will fall into the chasm and perish."

Just as the US responded protectively to Japanese automakers' rise, a similar scenario is unfolding with China's EV makers today. Regardless of whether it's Biden or Trump at the helm in 2025, it's hard to imagine a different US response than what we saw against Japan in the late 1970s/early 1980s when the Reagan government slapped it with a quota.

Perhaps a Biden administration will negotiate a Reagan-esc quota while his government 'investigates' national security concerns, while Trump will just slap them with an even higher tariff and claim he's doing everyone a favour. But regardless of which one wins office, they will work to delay the arrival of Chinese EVs just long enough for laggards such as Ford and GM to crack the code, keeping the US auto industry alive for another decade or two and preserving those valuable, but very costly, manufacturing jobs in Michigan.

The sacrificial lambs will once again be the US consumer and the global environment, given that blocking more economical Chinese vehicles in favour of oversized EVs built in the US will slow its transition to cleaner EVs.

Advantage, Australia

All of this is why I'm glad that this time around, we don't make cars in Australia; the political pressure to do something would have been too immense to resist. Sure, we may not be able to afford housing, but at least we'll be able to commute from the 'burbs in an efficient, affordable and well-made Chinese EV (that includes Teslas, Polestars, Volvos and some BMWs, which are now all made in China). And if China responds to US protectionism with even more EV subsidies, then all the better: we have no horse in this race, so as consumers of Chinese EVs we'll also benefit from any subsidies, at the Chinese taxpayer's expense.