Friday Fodder (8/24)

1. Where we're spending

When faced with a cost of living crisis, it's important not to just look at the cost of everything but also changes in relative costs. For example, if you were a politician trying to help struggling households and you just blindly threw cash at what the media was crowing on about, you might be missing what really matters to them.

Thankfully, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recently updated the weights in its consumer price index, a process it does every year to "reflect the relative amount spent on goods and services as a proportion of total expenditure by all households".

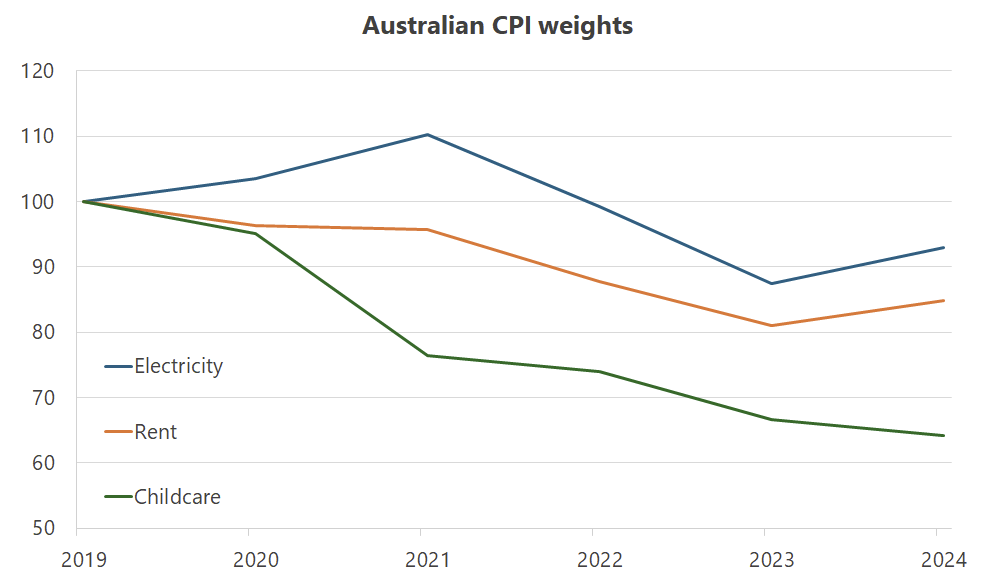

You might be tempted to think, based on the political and media attention given to the subjects, that electricity, rents and childcare would have seen the largest increases. But you would be wrong, with all three falling in their relative importance to households' budgets over the past five years:

But wait, you say! Government support has helped to suppress the sticker prices for all of these, such as the "changes to the Child Care Subsidy reducing out-of-pocket costs for households", various state and federal electricity subsidies, and the 15% increase to the Commonwealth Rent Assistance scheme.

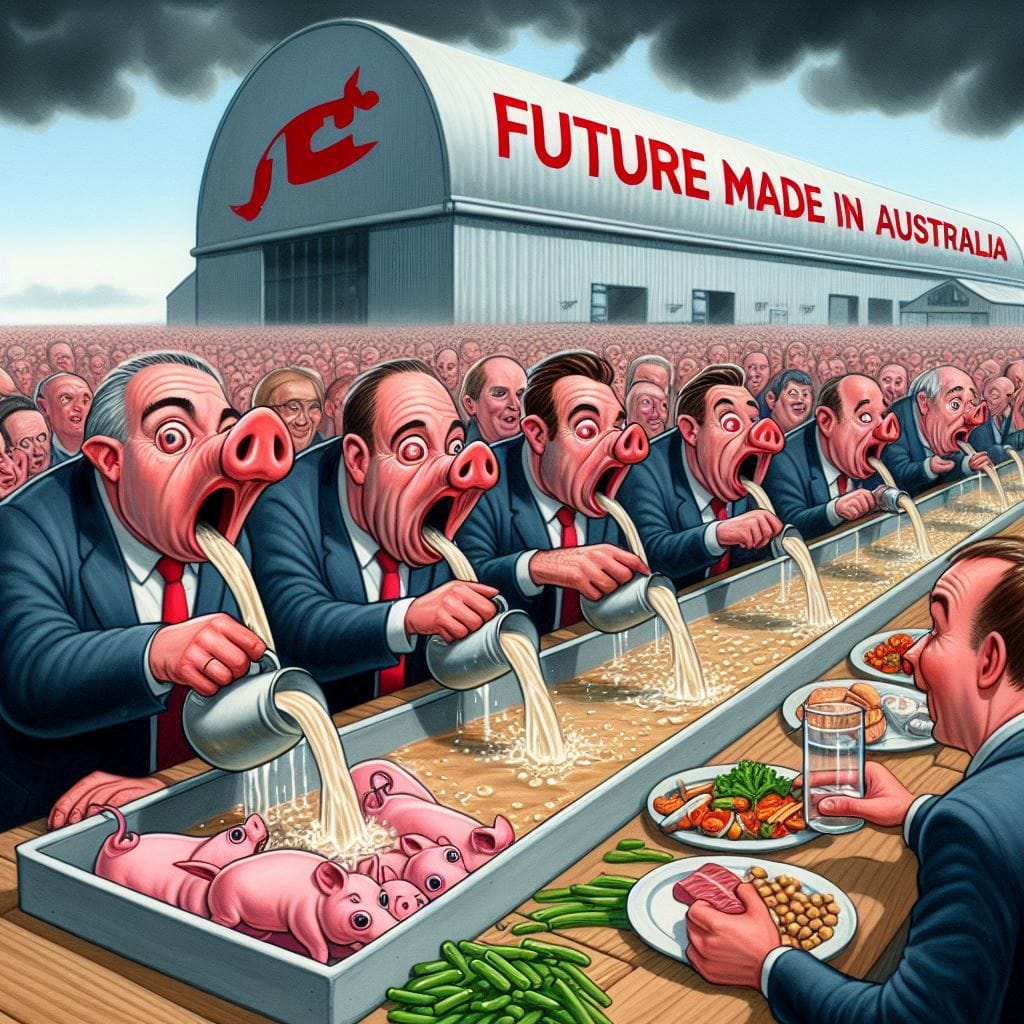

Job done, right? Not quite: even ignoring the deadweight losses (the money spent on subsidies could have produced more value elsewhere in the economy), those decisions also came with unintended consequences, such as huge profits for Australia's largest childcare companies, rising rents (even if tenants aren't paying all of it, yet), record-low rental vacancies, and blackouts.

These effects were entirely predictable, given that the elasticity of demand is greater than supply in all these sectors: in such markets, suppliers of childcare, electricity, and rental housing capture far more of the subsidy's benefit than do consumers of the goods and services. To make matters worse, the price suppression is also temporary; when the subsidies run out, measured prices will shoot right back up.

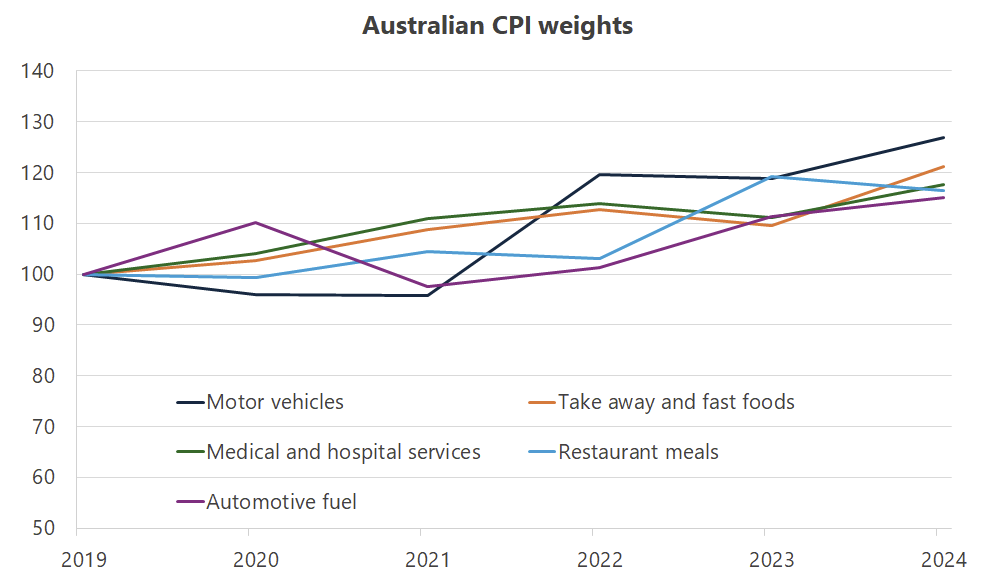

But if we look past electricity, rents and childcare, the real killers for household budgets over the past five years have been the rising cost of new cars (likely due to pandemic-related supply chain issues) and several key services, such as take away food and healthcare.

These five items now all have a weight greater than 3% (together they comprise nearly 20% of household spending) and have increased significantly since 2019 as a proportion of household spending. But given that vehicles and fuel are imported and the rest are all domestic services that have risen largely as a result of excessive aggregate demand, there's very little the government can do to help, other than to reduce its own contribution to aggregate demand (cut spending or raise taxes), or improve aggregate supply (economic reform).

I know that may not be what those in Canberra will want to hear, but life isn't all sunshine and lollipops.

2. China's pivot from growth to security

Earlier this week China's elite gathered around and announced their real GDP growth target for 2024, a routine that has become one of the best examples of Goodhart's Law going around:

"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

This year's growth target, for those who care, was "around 5%". China will inevitably reach that target, because the political cost of not achieving it in an economy that the government heavily manipulates would be too high. If that means cooking a few numbers, so be it. But achieving growth targets at all cost has caused considerable economic damage in the past, with the government resorting to short-term techniques such as inflating real estate construction to unsustainable levels – by some estimates, even China's entire population wouldn't be able to fill all of its empty homes.

The latest figure of 5% looks especially dubious because of how much China's economy has slowed. According to Scott Kennedy of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington:

"I think the scepticism inside China and outside China about the official data seems widespread and justified... the business community and investors in China are not convinced China has turned the corner."

China observers used to look at other data to get an idea of what was going on in China, such as the so-called 'Li Keqiang index', which included indicators such as electricity usage, rail cargo and bank loans. But even those aren't reliable these days; for example, when youth unemployment data started to look bad last year (>20%) the government pulled the data, only to release a new version a few months later using a new, more favourable (to the leadership) methodology.

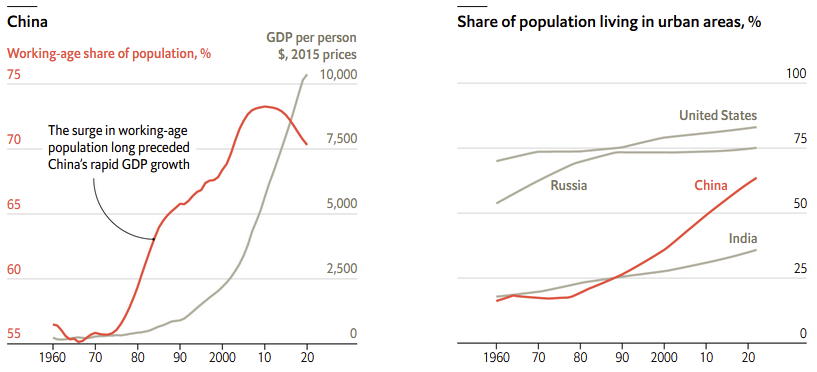

But there are also legitimate, economic reasons to think that the days of rapid real growth in China are over. Its demographic dividend peaked around the early 2010s, and its urban population ratio is now close to western levels.

Not only that but as Warren Buffet has discovered, it's very hard to grow at high rates off a larger base: China's level of GDP is now so large that double-digit growth is well beyond it, and given its structural issues even figures like "around 5%" are starting to look increasingly implausible. China may have truly "grown old before it has grown rich", a fate that was made more likely by Xi Jinping and his "atmosphere of distrust that fuels China's new security-first economic policy — one that is obsessed with maintaining control, and with stopping the outside world from undermining China from within".

3. It's a marathon, not a sprint

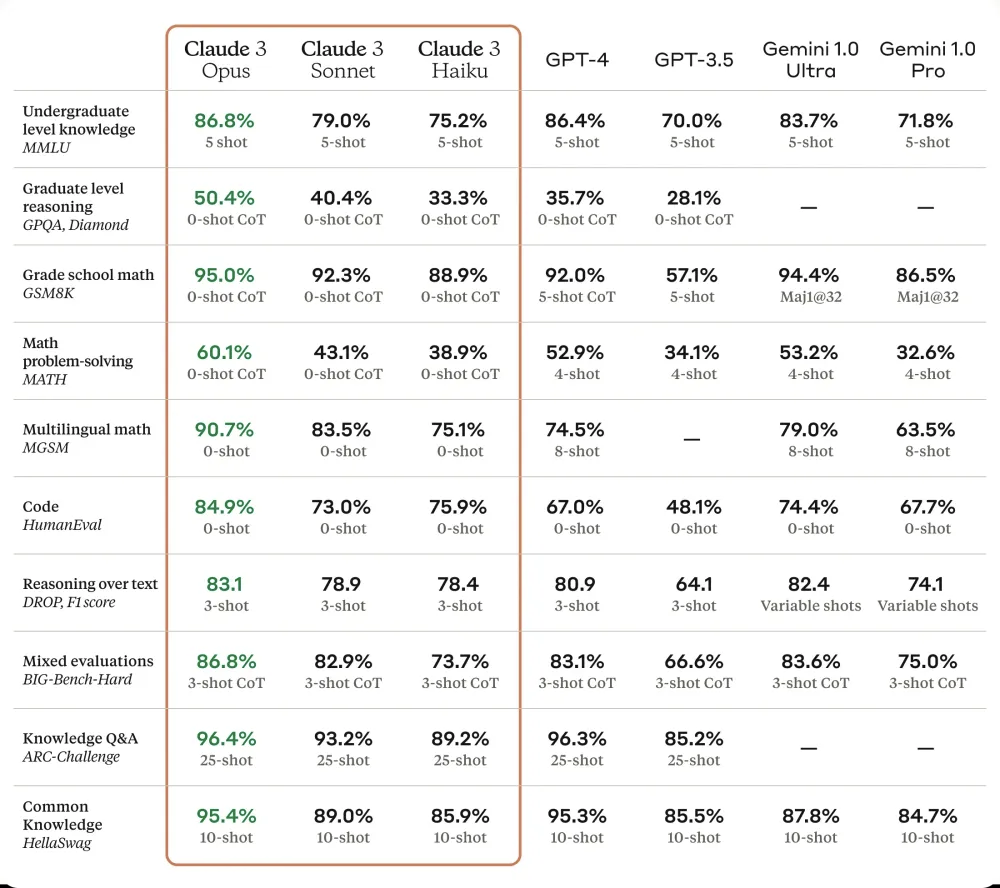

Anthropic's Claude AI just got a big upgrade to version 3, which it claims is now on-par, or better than, the market leading GPT-4 by OpenAI:

This is great news, for two reasons. First, competition is essential for a healthy market. If one of these AI companies had managed to 'build a moat' around the technology, we'd all be worse off: progress would slow, prices would rise, and a few fortunate individuals would become billionaires. Second, it offers choice: for example, we will almost certainly not have to live in a future dominated by Google's Gemini AI and its 'wokeification' of reality. With competition, I imagine these models will converge to something resembling the median voter.

But back to Claude. Joshua Gans provided an excellent summary of "the consequences of the massive proposed AI investments", and whether progress might start to slow now that a few companies have reached GPT-4 levels:

"I am very bullish on AI and want more sooner, but the hard-headed economist in me can’t help but wonder if such acceleration is justified. I am not talking about all of the debate about the potential harms from AI here, I am just talking about the plain old rate of return."

As for Claude 3 itself, The Zvi provided a comprehensive overview of the ins- and outs, including "the benchmarks, statistics and system card, along with everything else people have been reacting to".

4. Higher for longer?

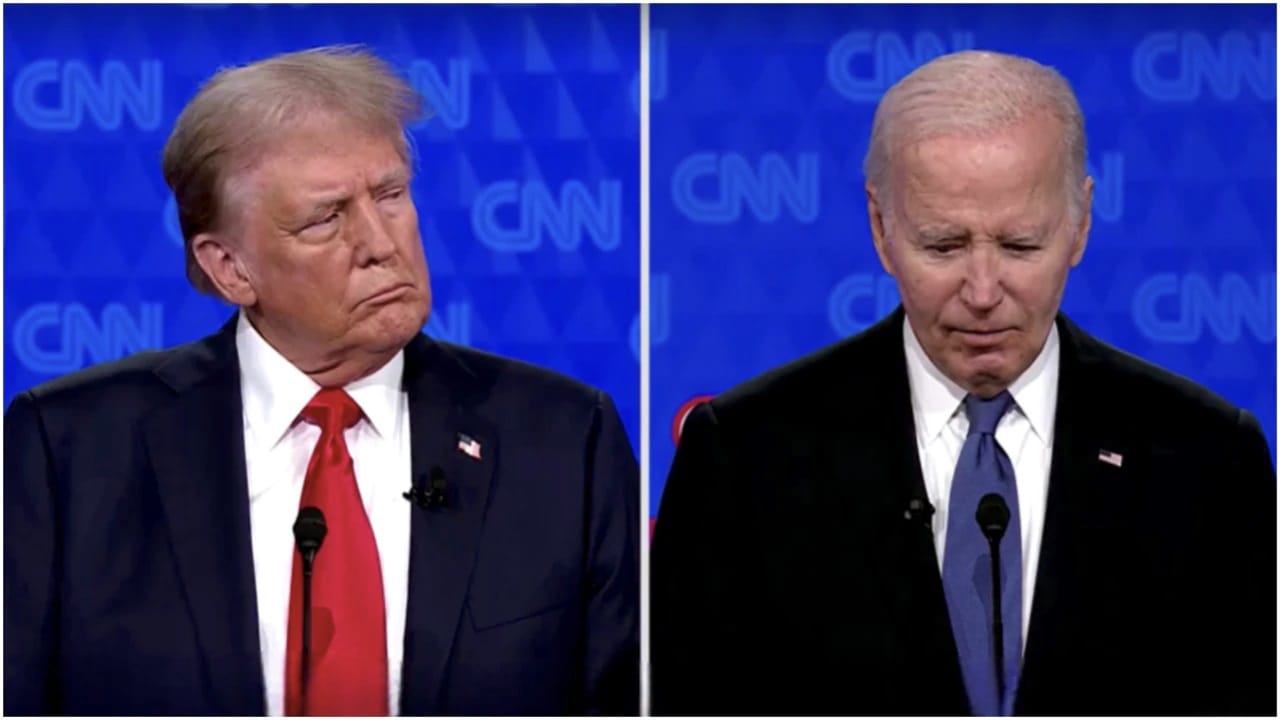

A couple of months ago I asked the question of when interest rates might start coming down, concluding that inflation – and therefore interest rates – could prove to be stubbornly high for several months to come. Last Friday, Torsten Sløk of Apollo (a fund manager) took a look at the US economy and concluded much the same:

"[T]he Fed will not cut rates this year, and rates are going to stay higher for longer."

Sløk provided a dozen pieces of evidence – including charts – to support that conclusion; far too many to replicate here. Obviously, a lot can change in the next 9 months, so Sløk may well end up being wrong. For example, would the Fed refuse to cut rates were China to invade Taiwan? Unlikely!

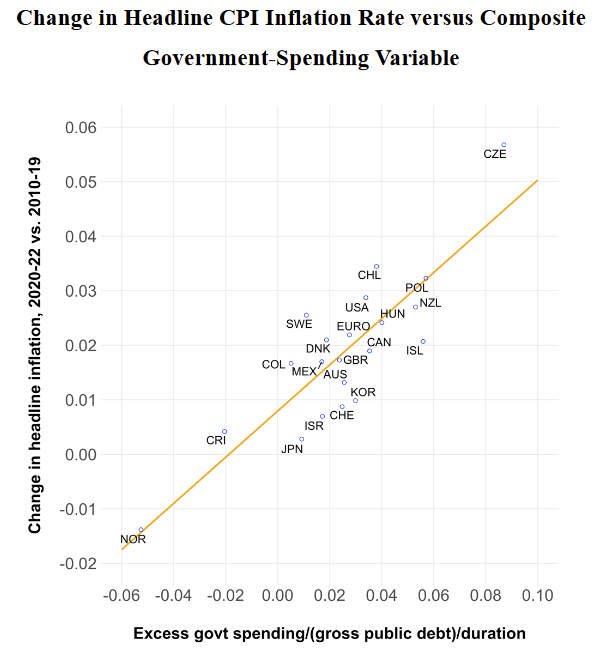

From an Australian context, the US is ahead of where we are. If these recent signs of increased inflation in the US are the start of a new trend, rather than just noise, then the same could well happen here. After all, countries reaped inflation in proportion to their excessive pandemic-related spending (financed with a considerable amount of newly printed money):

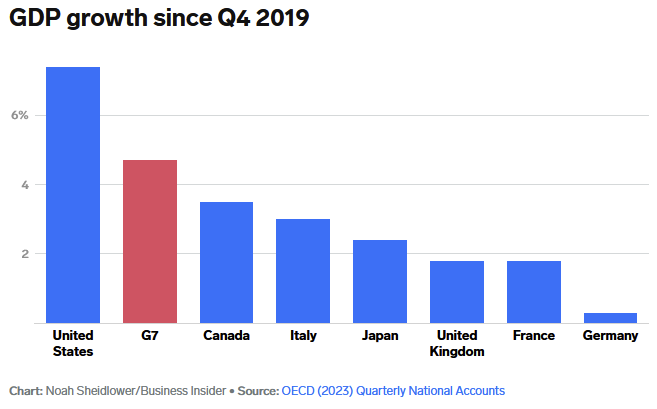

A major difference between the US and most other advanced economies is that the US is growing considerably faster, except for Australia, which at around 9% growth since December 2019 would sit above even the US in the following chart.

Growth in Australia has started to slow but certain inflationary forces, such as debt-financed government spending, have not: of the 1.6% growth we recorded in 2023, 75% came from public demand. Since December 2019, nearly 57% of Australia's real GDP growth has come from public demand.

Have a great weekend.

5. And if you missed it, from Aussienomics

Death by a thousand links – Facebook leaving Australia shows that the media bargaining code backfired. The government misdiagnosed the problem and harmed consumers while benefiting the big media companies. It's time to cut our losses, accept that the code was a mistake, and focus on real solutions to support local media.

It's a good thing we don't make cars any more – Chinese cars offer great value and affordability, but US automakers are lobbying for protection, just as they did with Japan in 70s. Fortunately, Australia's lack of auto manufacturing means that this time around, we can enjoy the full benefits of competition!

Member discussion