The unintended consequences of the vaping crackdown

A couple of weeks ago, late on a Friday, the federal government released an Impact Analysis from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), dated October 2023. The analysis was on the government's "Proposed reforms to the regulation of vapes", and is what informed the 28 November announcement to "implement a ban on the importation of disposable single use vapes", along with the adoption of a new prescription model:

"In parallel with this ban, a new Special Access Scheme pathway to prescribe vapes will commence on 1 January 2024, which will facilitate improved access to therapeutic vapes, whereby all medical practitioners and nurse practitioners will be able to prescribe their use where clinically appropriate."

The government isn't stopping there: later this year the crackdown will expand into limiting flavours, requiring pharmaceutical packaging, and banning "domestic manufacture, advertisement, supply and commercial possession of non-therapeutic and disposable single use vapes".

It's clear the government wants to "turn the tide against the rising use of vapes by young Australians". But rather than take the Health Minister's words at face value, us economists like to distinguish between what sounds good and what works – so here we go!

The immediate cost of the reforms

Straight off the bat, the government estimates the new laws will cause an annual regulatory burden of $59.5 million, which covers the expected "compliance activities required by the TGA", but excludes the costs imposed on the potentially thousands of vaping stores that will now have to close.

Most of those estimated costs (over $50 million), are from the two annual GP visits Australia's vapers will need to attend to get a prescription, along with a monthly pharmacy interaction to acquire vapes. The numbers involve a lot of assumptions, such as that only 450,000 of Australia's estimated 1.3 million vapers will seek a prescription, and that 80% of them will be able to see a bulk billed GP (good luck with that – in WA, only 10% of clinics still offer that option).

In addition to the regulatory burden, the government will provide $25 million to Australian Border Force to enforce the import ban and $56.9 million for the TGA over two years to introduce the reforms, along with "$29.5 million in funding to help Australians quit".

Overall, the reforms are a huge win for doctors and pharmacists, who now have yet another ticket to clip. At the margin, higher prices (time and cost) and a decline in quality (fewer options) could force people onto what looks set to be a lucrative black market, as it has done for cigarettes.

According to the Health Minister:

"Mr Butler said the illegal tobacco market was an 'ATM' for organised crime, which funded other criminal activities including drug and sex trafficking.

He said estimates from the Australian Tax Office suggested the tobacco black market was costing taxpayers more than $2 billion every year in lost revenue.

'Everyone is paying a price for this activity,' he said."

The excise tax on a cigarette is currently $1.24, so the $2 billion in lost revenue is equivalent to over 1.6 billion cigarettes, or around 80 million packets, being bought on the black market each year. If vapes join cigarettes as an attractive option for traffickers, then another winner from the reforms will be local gangs and criminal enterprises, who will have a new product they can sell to raise revenue.

What's wrong with vapes

Before getting into the economic impacts of these reforms and offering a better alternative, I want to briefly touch on why the government decided to effectively ban vapes in the first place. According to Health Minister Mark Butler:

"We know that vapes pose a range of known and unknown risks to Australians, particularly among young people. The latest data, from the first quarter of 2023, shows that about one in seven 14- to 17-year-olds and one in five 18- to 24-year-olds are current vapers. There is strong and consistent evidence that young Australians who vape are around 3 times more likely to take up tobacco smoking compared to young Australians who have never vaped."

All of that is true, but the Minister is not telling us the whole truth. When someone says 14- to 17-year-olds are doing a lot of bad stuff, I want a benchmark of some kind; to know if those kids are doing other bad stuff that the government has already restricted, or if vapes are somehow special. So I had a look, and according to the government's survey data:

- 7% of secondary school students aged 12–17 had smoked in the last month.

- Almost half (46%) of those aged 12–17 drank alcohol in the past year, and 27% had done so in the past month.

- 8% of students aged 12–17 had used cannabis in the month before the survey and 16% reported using cannabis in their lifetime, making cannabis the most commonly used [illicit] drug in this cohort.

- 18% of students had deliberately sniffed inhalants at least once in their lifetime, with 7% reporting doing so in the past month.

Vaping was illegal for 14- 17-year-olds before the recent crackdown, yet around 14% still vaped. Cigarettes and alcohol are also illegal for those aged under 18 but the cohort in question still manages to use those at rates of 7% and 27%, respectively. Cannabis is illegal for everyone, yet around 8% of kids still use it.

It's almost as though certain kids will try to smoke, drink or inhale bad stuff regardless of the rules! Banning vapes will no doubt see some kids stop using them, but many will simply switch to another vice.

But the most egregious part of Minister Butler's statement was the statistical sleight of hand he pulled at the end. Well, that or he's innumerate: while it may well be true that young Australians who vape are around 3 times more likely to take up tobacco smoking, those individuals probably have a number of other traits that correlate well with their eventual tobacco smoking, too. In statistics we call those confounders, and if you don't even attempt to control for them, your correlation is worth precisely zero – the observed dynamic of vapers becoming smokers could be caused by something completely unrelated to the vaping. In this case, the missing confounders are probably also the reason why those 14% of kids vaped to begin with.

Vapes are bad but the alternative is worse

When you ban something, it doesn't just go away. If there's a will (demand), there's a way (supply), and the same will be true for vaping: instead of disappearing, flavoured disposable vapes will vanish from tobacconists and move to where underage kids currently source many of their vapes, including under the counter at convenience stores, through social media, and on websites.

No doubt for some it will become too difficult, and they'll quit or find some other illicit substance to try. Frequently, that substance is tobacco: a 2015 study published in the Journal of Health Economics found that when states banned vapes, they yielded "a statistically significant 0.9 percentage point increase in recent smoking in this age group [12-17], relative to states without such bans... banning electronic cigarette sales to minors counteracts 70 percent of the downward pre-trend in teen cigarette smoking for a given two-year period".

Vapes are a direct substitute for cigarettes. While some people will do both, there are benefits to getting smokers off cigarettes and on to vapes. According to a 2020 paper in the European Heart Journal, "there are several studies demonstrating an improvement in endothelial function in response to switching from tobacco to e-cigarettes". An earlier 2018 research paper by Georgetown University found that "a strategy of replacing cigarette smoking with vaping would yield substantial life year gains, even under pessimistic assumptions regarding cessation, initiation and relative harm".

As for vapes being a 'gateway' to smoking, a 2022 paper in Preventive Medicine found the opposite effect:

"[I]n this paper, we propose an evidence-based version of this model based on several years' worth of longitudinal and econometric research, which suggests that youth e-cigarette use has instead worked to replace a culture of youth smoking. From this analysis, we propose a re-evaluation of current policies surrounding e-cigarette sales so that declines in e-cigarette use will not come at the cost of increasing cigarette use among youth and adults."

While the long-term effects are still mostly unknown, the government didn't ban microwaves, telephones, Wi-Fi, radios, or video games, despite claims at the time that those would cause unknown long-term harms. Today, most of the vaping injuries and deaths are caused by "black market modified e-liquids... This is especially true for vaping products containing THC", and those that illegally use vitamin E acetate as a thickening agent. The long-run health effects might be unknown for vapes, but is that worse than the known adverse long-run effects of smoking? Unlikely, and that's the relevant trade-off we must consider here.

Misapplying the precautionary principle

What's odd about the government's latest vaping crackdown is that we usually ban things before they've become popular. If we didn't, tobacco and perhaps even alcohol would have been banned decades ago (notwithstanding the mountains of literature and lived experience on how prohibition doesn't work). The cynic in me suspects the difference is because alcohol and tobacco raise considerable tax revenue, while vapes detract from it by causing people to substitute away from cigarettes. From a political incentive point of view, that makes sense, but it would take an entire essay to adequately cover it so I'm going to invoke Hanlon's razor and move on.

By making vapes prescription only, the government has opened Australians up to a litany of potential unintended consequences. According to a 2022 meta analysis of 30 papers in BMC Public Health, when jurisdictions restricted vapes, usage was replaced with "increased cigarette use, and increased use of illicit markets". When specific flavours were banned, "6–39% of stores [still] sold restricted flavoured products post-restrictions", and "[o]nline stores remain a potential source of restricted products". When San Francisco banned flavoured vapes, "cigarette smoking increased... [and] users reported being able to obtain flavored tobacco products in multiple ways despite the ban".

Another 2022 study published in Value in Health found that a "full ban on ENDS [vapes] was associated with increased cigarette sales of 7.5% in Massachusetts. Banning non-tobacco flavored ENDS was associated with a 4.6% increase in cigarette sales."

If your policy causes people to trade vapes for cigarettes – which the evidence suggests this almost certainly will do – then you're causing harm.

Back in Australia, a 2020 study published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research argued that the Australian government misapplied the precautionary principle in its initial war on vapes (Morrison government), because it:

"...failed to consider the regulation of similar products, imposed regulations that are disproportionate to the level of risk, failed to assess the costs of its regulatory approach, and failed to undertake a cost/benefit analysis of a range of available regulatory options".

For whatever reason, successive governments and the health establishment in this country have been anti-vape from day one, and no amount of evidence has been able to persuade them otherwise. Like ostriches with their heads buried deep in the sand, they have only thought about vapes in a vacuum rather than in a continuum, creating a perverse situation where cigarettes are available over the counter yet vapes – which cause far less harm – are now prescription-only medication. It's a model akin to one where you would need a prescription for light beer but can still walk into your local supermarket and get yourself some hard spirits.

Baffling, really.

While no amount of evidence is likely to convince this government to change its mind, as the political cost of a U-Turn would be too high, there is a better way.

A more humane option

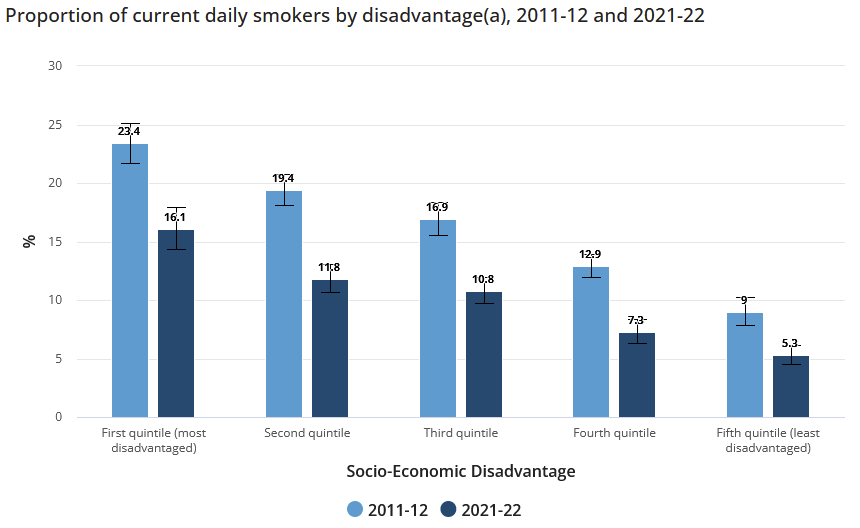

You have to remember that for most people the choice is often not between vaping and doing nothing bad at all, but between vaping and cigarettes, and the overwhelming consensus is that vapes are significantly less harmful than cigarettes. Just over 10% of Australians aged over 15 still smoke, so around 600,000 people, and most come from disadvantaged parts of society. Helping them get off cigarettes would be a massive boon for their health and hip pockets.

Vaping has been proven to be one of the more effective methods of quitting cigarettes. An analysis of 88 studies that compared vapes to alternative methods of quitting, such as nicotine patches and gum, found that:

"Nicotine e-cigarettes can help people to stop smoking for at least six months. Evidence shows they work better than nicotine replacement therapy, and probably better than e-cigarettes without nicotine."

By increasing the cost of vaping and making it a less viable alternative to cigarettes, including by limiting the availability of different flavours, the government is eroding the ability of vapes to substitute for cigarettes:

"The results of this survey confirm previous observations by finding that dedicated users switch between flavours frequently and the variability of flavours plays an important role both in reducing cigarette craving and in perceived pleasure. Moreover, the number of flavours used was associated with smoking cessation. Therefore, flavours variability is needed to support the demand by current vapers, who are in their vast majority adults."

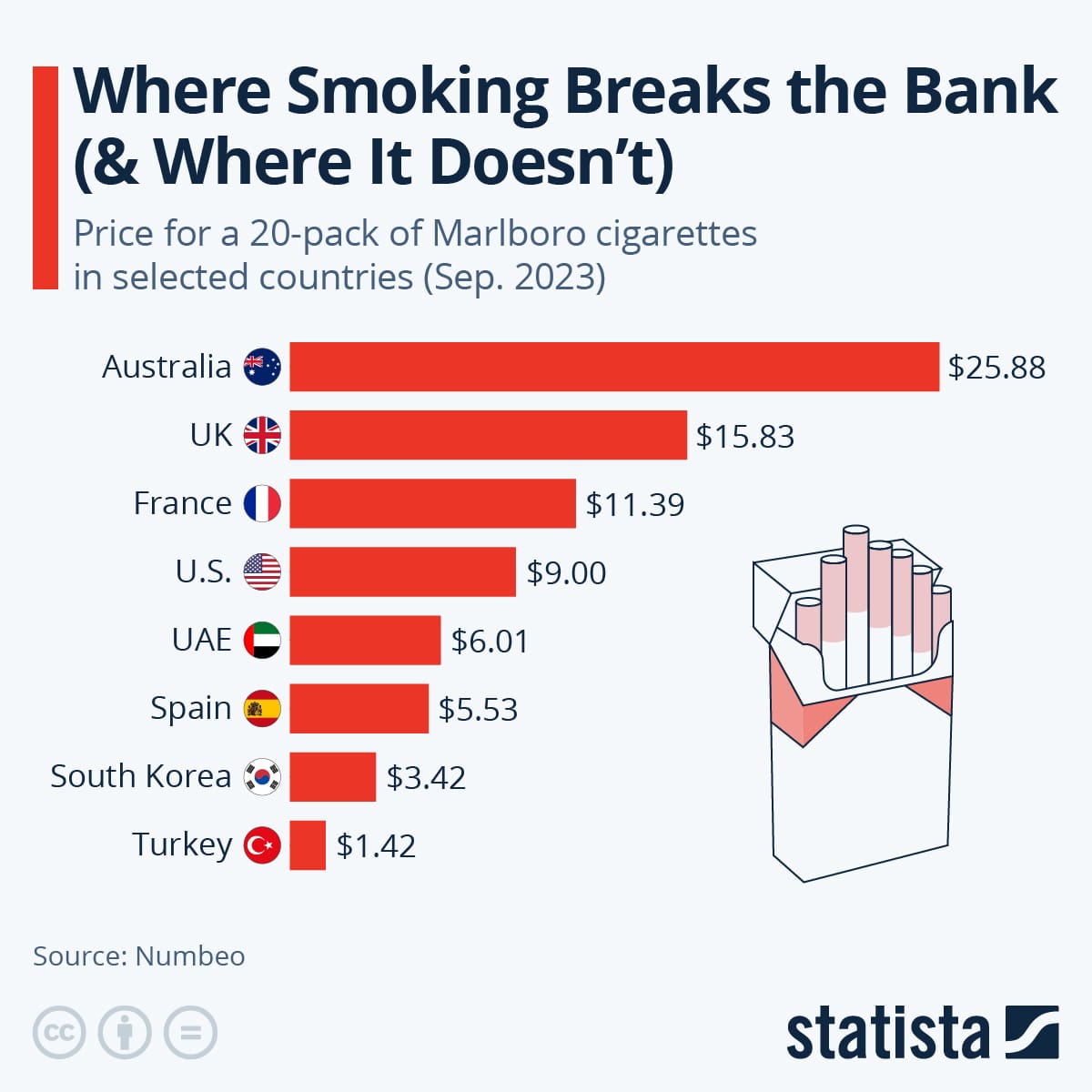

Instead of demonising vapes and punishing society's most disadvantaged, the government should implement standards for vapes in the same way it does for other harmful substances that people enjoy, such as alcohol, and actually enforce them. Don't want kids to vape? Rather than spending tens of millions of dollars bulking up the Australian Border Force to fight a war it will never win, legalise them and spend that money on education and enforcing the existing age limits instead. Go ahead and tax the sale of vapes (noting that 10% is already captured by the GST), but don't get anywhere close to cigarette levels; the goal should be to prevent a black market – an avenue also frequented by children – from becoming viable, while also incentivising smokers to make the switch to a less harmful product.

We screw up a lot of public policy in this country. But it's rare to see an example so clearly fly in the face of the available evidence as the government's approach to vapes has done.

Member discussion