Friday Fodder (4/24)

Here are a few short takes for you to chew over on the weekend, from the week's happenings that probably didn't need a full post.

1. Confusing cause with effect

Former chair of the ACCC, Allan Fels, released his much anticipated report into "price gouging and unfair pricing practices" on Wednesday, and let's just say it's a good thing Fels has been out of public policy making for over 20 years.

Why am I being so harsh? Throughout the report, Fels mistakes profit for profitability and the causes of inflation with its symptoms. His thesis is perhaps best summarised on page 19:

"Companies took advantage of the resulting shortages and disruptions [caused by the pandemic] to increase prices well above their costs. Businesses in many (but not all) industries were willing and able to push up prices, yet still sell their products. Their actions constituted the leading edge of post-pandemic inflation."

Inflation is defined as an ongoing increase in the price level for all goods and services. The European Central Bank offers a helpful explainer:

"In a market economy, prices for goods and services can always change. Some prices rise; some prices fall. Inflation occurs when there is a broad increase in the prices of goods and services, not just of individual items; it means, you can buy less for €1 today than you could yesterday. In other words, inflation reduces the value of the currency over time."

The idea that enough firms are able to "push up prices, yet still sell their products", to the extent that they cause the prices for all goods and services in Australia to continuously rise relative to money, is preposterous.

For one, from where did this pricing power suddenly come? Fels tries to explain this inconvenient question away by asserting (p.23) that firms "have been able to leverage the disruptions and uncertainty that followed the COVID pandemic into unprecedented profitability". They have supposedly "accomplished" this through "behavioural mechanisms", stemming "from a common, underlying force: the desire and ability of companies to lift their prices well above production costs".

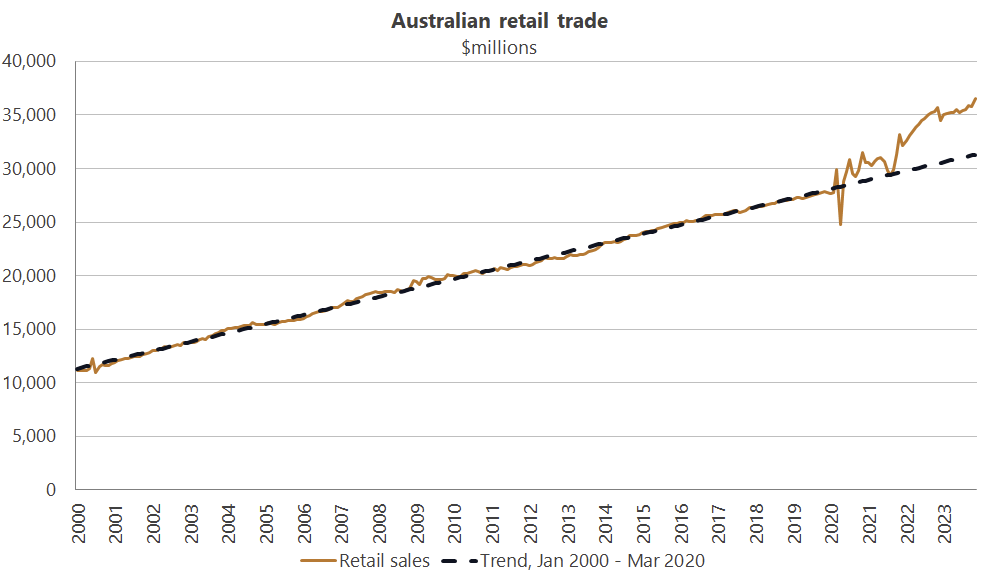

But that "desire" is a constant. How dumb does Fels think consumers – who are also self-interested and greedy, and are at least as likely to push prices down as up – really are? That they will be confused by "disruptions and uncertainty" for so long that firms in "many" industries were able to exploit them for years on end? That they can simply dig into their savings and spend 50% more on retail goods in the space of three years?

While it's true that some firms probably have pricing power in Australia – Fels cites Qantas, which he claims was "aggressively raising airfares" in December 2022, contributing to a "quarter of the inflation that month" (a claim that is demonstrably false, regardless) – but they can't cause inflation. The price of a Qantas airfare might increase relative to other goods, but it can't push up overall prices. If Qantas has monopoly pricing power and can raise prices without affecting quantity demanded, then consumers will have to spend less on other things, lowering their prices.

Part of Fels' confusion appears to stem from his misunderstanding of inflation: the consumer price index (CPI) is only a measure of inflation, and "does not adjust for changes in household spending patterns very often". Not understanding the distinction between a measure of inflation and inflation itself may be one reason how Fels ended up getting it so wrong.

The pandemic greatly disrupted patterns of exchange, helping to obscure inflation as measured by the CPI. But it was already baked in. When our economy eventually reopened it was the increased demand caused by fiscal/monetary stimulus, combined with the same – or in some cases, less (pandemic disruptions) – supply, that pushed up prices and short-term, nominal profits. The profits came about because firms are able to respond to demand by raising prices (revenue) faster than workers can bid up wages (costs). This phenomenon is worse in Australia than countries during periods of inflation, given our relatively higher rate of collective agreements that average around 3 years in length.

Businesses don't have printing presses; the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) does. The only way we get excessive inflation is if the RBA makes a mistake. In this case, the RBA overestimated the demand and supply shock caused by the pandemic and keep monetary conditions too easy, for too long. It failed to adequately offset the unprecedented fiscal stimulus unleashed by our state and federal governments, and with more dollars chasing the same (or fewer) goods and services, prices and short-term profits increased.

Look, I agree with Fels that we should end the government's protection for firms such as Qantas that clearly demonstrate pricing power on domestic routes. But that's not what caused the inflation, and a lot of Fels' other recommendations would lead to poor outcomes for consumers.

2. A cure for dengue

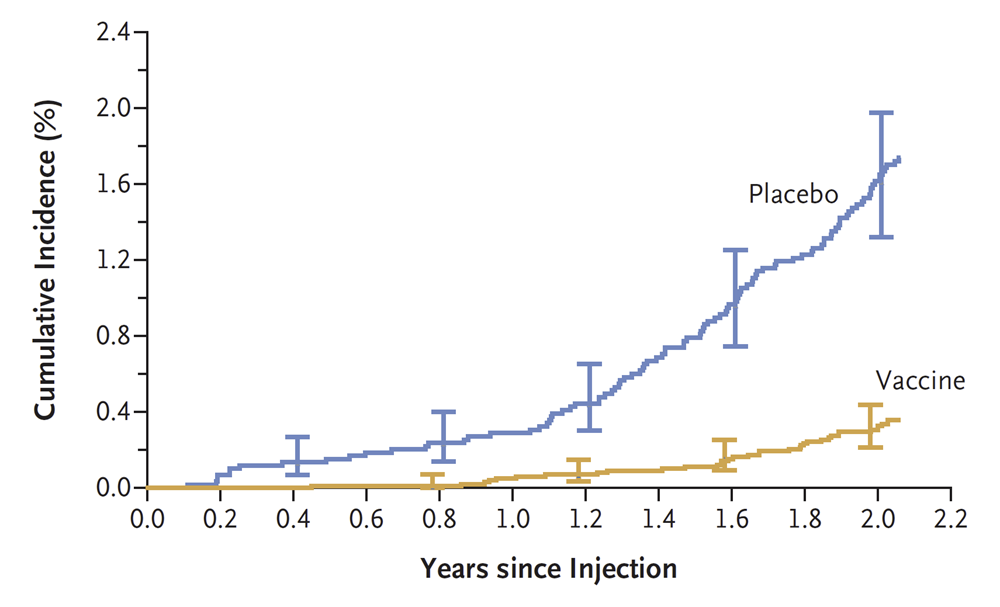

The mosquito-borne Dengue virus killed up to 40,000 people in 2019 alone. Now we might have a vaccine:

"In a trial involving 16,235 persons in Brazil, the live, attenuated, tetravalent Butantan vaccine was efficacious in all age groups at 2 years."

The vaccine provided 80% protection from a single dose (all four-strains of Dengue) among those with no prior exposure, and 89% protection in those with a history of exposure.

If true, it's amazing news. Mosquitos are by far the most dangerous animal in the world. Even more dangerous than we are to ourselves!

3. The design of war has changed

We spend a lot on aircraft, vehicles, ships and submarines in this country – even if some of it is never "fit for purpose", such as the Taipan helicopter.

Even the stuff that works is what I'd be tempted to call old tech, useful for fighting the last war. But Russia's invasion of Ukraine has flipped the thinking about how to defend yourself against a larger, more heavily armed opponent. Ukraine's army chief, Valerii Zaluzhnyi – who, incidentally, has been fighting internally with Vladimir Zelenskyy (it's going to be fascinating how that plays out) – recently penned an opinion piece for CNN, arguing that a lot of what we're investing in today will probably be useless if we ever tried to use it against a major power:

"It is well known by now that a central driver of this war is the development of unmanned weapons systems.

They are proliferating at a breathtaking pace and the scope of their applications grows ever wider.

Crucially, it is these unmanned systems – such as drones – along with other types of advanced weapons, that provide the best way for Ukraine to avoid being drawn into a positional war, where we do not possess the advantage."

Australia is a big, sparsely populated island, so it doesn't make sense to invest in a bunch of manned vehicles and vessels that have Buckley's chance of repelling a much larger, well-equipped force. Instead, we should probably be investing far more in relatively low-cost, high-tech, unmanned devices:

"The remote control of these assets means fewer soldiers in harm's way, thus reducing the level of human losses.

It offers the opportunity to reduce (though certainly not eliminate) reliance on heavy materiel in combat missions and the overall conduct of hostilities.

And it opens up the possibility of inflicting sudden massive strikes against critical infrastructure facilities and communications hubs without deploying expensive missiles or manned aircraft."

The good news is our Department of Defence is looking at bulking up our stock of drones and counter-drone capability. The bad news is that they plan to take eight years just to make a decision on what to acquire!

Yep, we're screwed.

4. Phishing for more

In 2022 Australians lost $3.1 billion to scams, up 80% from 2021. According to ACCC Deputy Chair Catriona Lowe:

"Despite fewer reports to Scamwatch, losses experienced by each victim rose by more than 50 per cent last year, to an average of almost $20,000.

This is due, in part, to scammers using new technology to lure and deceive victims.

'Scammers evolve quickly and unfortunately, many Australians are losing their life savings', Ms Lowe said.

'We have seen alarming new tactics emerge which make scams incredibly difficult to detect. This includes everything from impersonating official phone numbers, email addresses and websites of legitimate organisations to scam texts that appear in the same conversation thread as genuine messages. This means now more than ever, anyone can fall victim to a scam'."

That figure might be about to get a lot bigger, as scammers are increasingly using AI to attack everything from banking to porn. In Hong Kong, a finance worker at a multinational firm was recently tricked into making a "secret payment" of $25,000 via a team video chat:

“(In the) multi-person video conference, it turns out that everyone [he saw] was fake,” senior superintendent Baron Chan Shun-ching told the city’s public broadcaster RTHK.

Chan said the worker had grown suspicious after he received a message that was purportedly from the company’s UK-based chief financial officer. Initially, the worker suspected it was a phishing email, as it talked of the need for a secret transaction to be carried out.

However, the worker put aside his early doubts after the video call because other people in attendance had looked and sounded just like colleagues he recognized, Chan said.

With more people working remotely, phishing scams such as this – which with AI an attacker can execute quite cheaply, with as little as a legitimate LinkedIn profile and a bit of time – are surely only going to increase.

The lesson: don't give away anything, to anyone, without verifying via some form of multi-factor authentication first!

5. The secret to Trump's success

"You can't defeat an opponent if you refuse to understand what makes him formidable." - Bret Stephens.

Regardless of what you might think about Donald Trump the person, there's no denying he's a formidable politician. The NYT's Bret Stephens – a person who admits to have "consistently opposed him" – had a good look at the political machine that is Trump, from the perspective of "someone who wants him to lose":

"Trump got three big things right — or at least more right than wrong.

Arguably the single most important geopolitical fact of the century is the mass migration of people from south to north and east to west, causing tectonic demographic, cultural, economic, and ultimately political shifts. Trump understood this from the start of his presidential candidacy in 2015, the same year Europe was overwhelmed by a largely uncontrolled migration from the Middle East and Africa.

...

The second big thing Trump got right was about the broad direction of the country. Trump rode a wave of pessimism to the White House — pessimism his detractors did not share because he was speaking about, and to, an America they either didn't see or understood only as a caricature. But just as with this year, when liberal elites insist that things are going well while overwhelming majorities of Americans say they are not, Trump's unflattering view captured the mood of the country.

...

Finally, there's the question of institutions that are supposed to represent impartial expertise, from elite universities and media to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the F.B.I. Trump's detractors, including me, often argued that his demagoguery and mendacity did a lot to needlessly diminish trust in these vital institutions. But we should be more honest with ourselves and admit that those institutions did their own work in squandering, through partisanship or incompetence, the esteem in which they had once been widely held."

Australia will hold a federal election just four months after the United States unless, as some expect, it's called earlier to capitalise on the modified stage 3 tax cuts and potential cash rate relief. While opposition leader Peter Dutton might have the charisma of a turnip, there's a lot he can learn from Trump. For one, immigration is suddenly a big issue in Australia because of the large rates of growth the media is reporting in the official data, despite the fact the net increase was always going to be temporary. The Liberal Party successfully campaigned on a variation of this issue back in 2013.

Second, people are quite pessimistic about the economy: employment might be at record highs but the cost of living crisis is overwhelming everything else. You also have to remember that while employment is extremely important for people, ultimately they're working so that they can consume. Many are having to work longer hours or pick up second jobs to get by. You can be sure that the Liberal Party, despite playing the leading role in causing the crisis, will remind people that the Albanese government hasn't done all that much to make it any better.

I don't think faith in our institutions have been eroded anywhere nearly as much as in the US – perhaps the Reserve Bank of Australia is the only one to lose more credibility than its US equivalent, the Federal Reserve (which is receiving praise for a 'soft landing') – but two out of three 'Trump cards' should still worry any incumbent government facing an election.

6. And if you missed it, from Aussienomics

The need for tax reform: We desperately need tax reform in this country and fixing bracket creep for good would be an excellent feather for Chalmers to put in his rather empty reformist cap.

Miles off the mark: Queensland's Premier Steven Miles appears to be out of his depth. Last week he called for RBA rate cuts, and announced reviews into supermarket pricing and homelessness. On Sunday he released a rental package that risks making the situation worse.

Member discussion