Inflation and Australia's cost-of-living crisis

I thought I'd kick the year off by commenting on perhaps the biggest issue facing the average Australian last year, and one that looks set to continue in 2024: inflation and the cost-of-living crisis. According to the ABS:

"The rise in annual living costs for employee households is the largest increase since this series started in 1999. The last time the CPI recorded an annual increase of 9.6 per cent was in 1986."

Employee households – who rely primarily on wages and salaries for their income – have borne the brunt of the recent inflation, largely due to rising interest rates. These households tend to rent more than other cohorts or have relatively new mortgages, and both rental and mortgage costs have increased sharply in the past year. But no group has done especially well; most households have fared as bad, or worse, than indicated by the CPI (which doesn't include mortgage interest charges).

Treasurer Chalmers has indicated that he is aware of the problem, citing it more than half a dozen times in his relatively short Budget update speech in December. But I don't think Chalmers' cost-of-living policies will do much to fix the crisis, largely because he doesn't appear to understand how we got here in the first place.

How we got into this mess

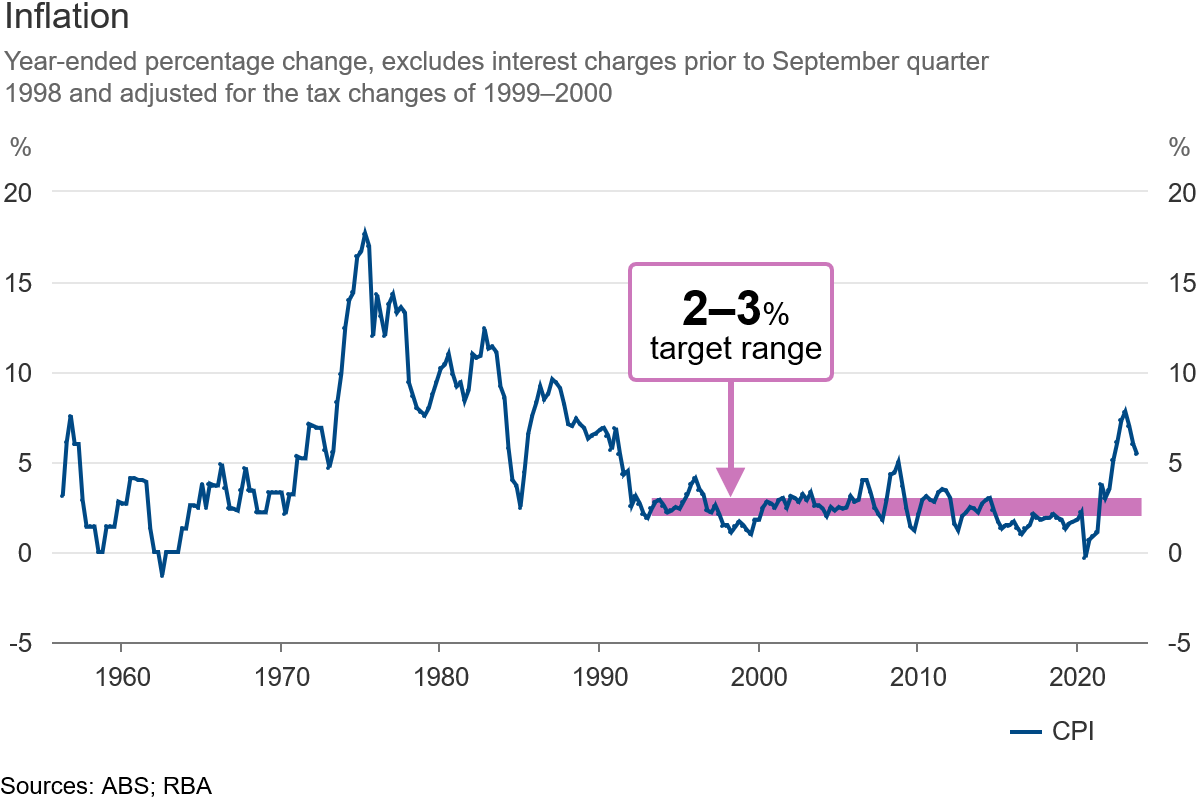

The cost-of-living crisis would almost certainly be significantly smaller without the unexpected wave of inflation that struck in 2021-22. The RBA produces a nice chart that visualises the recent jump well above its 2-3% target range, with annual consumer price increases peaking at 7.8% back in December 2022.

The inflationary shock took almost everyone by surprise. Indeed, the RBA's Governor at the time, Philip Lowe, infamously predicted that because the central bank perceived no risk of inflation, interest rates would remain at historic lows until "at least 2024", a call that ultimately cost him his job:

"The fact that many people interpreted the forward guidance as 'a promise' that there would be no rate raises until 2024 led to considerable reputational damage to the Bank. When the cash rate was increased in May 2022, many people saw the Bank as having broken 'its promise'."

So just what caused the first major bout of inflation in Australia since the late 1980s? There's no straightforward answer, and it's important to remember that the experience has not been unique to Australia; just about every developed economy has seen inflation run away and encountered some variety of cost-of-living crisis. But the economists' usual suspects, demand and supply, go some way to explaining what went wrong.

The pandemic's supply shock

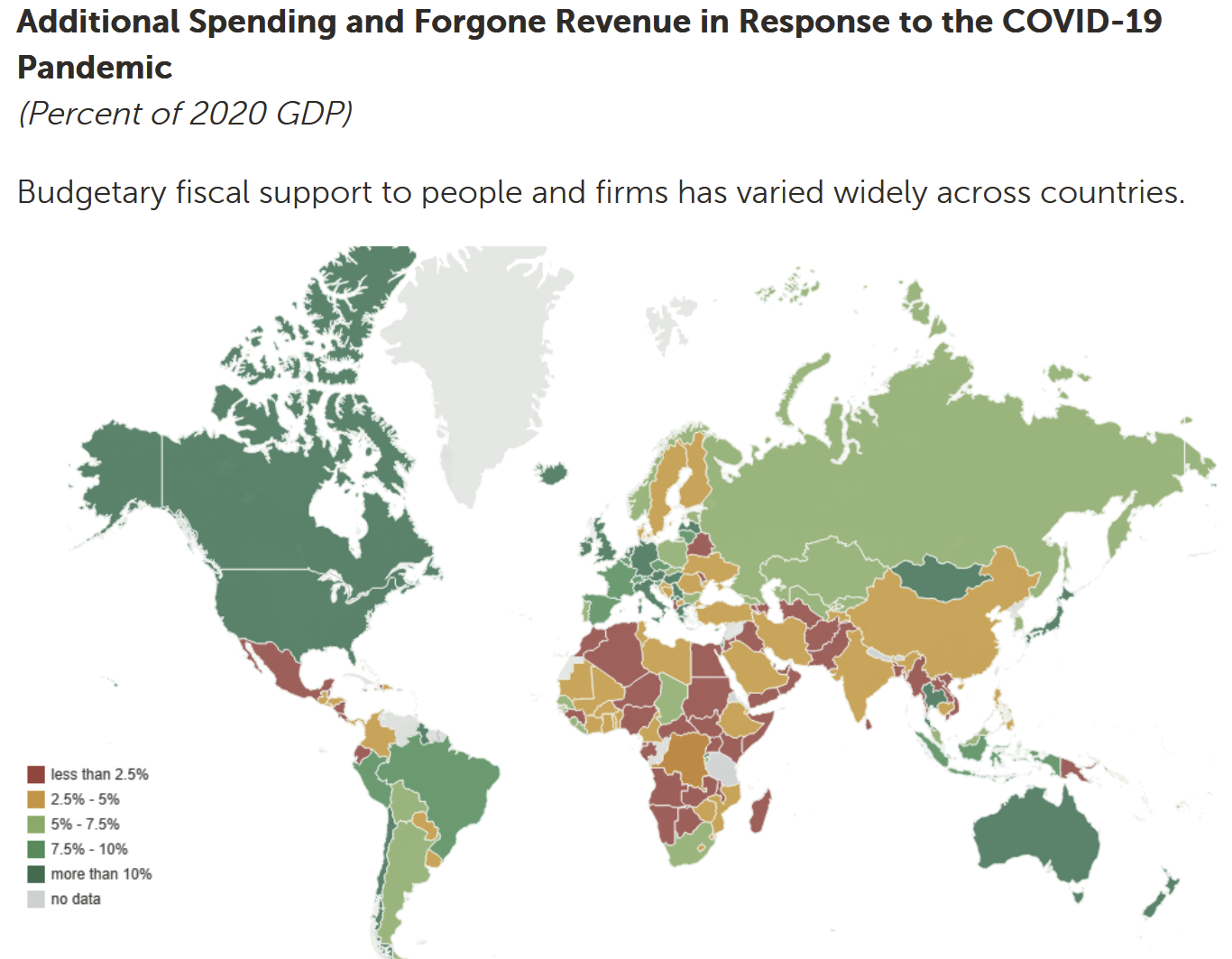

The supply shock came first: during the pandemic, governments closed their borders, ordered people to stay home and avoid public gatherings. With fewer services to spend their incomes on, and generous government hand-outs ensuring that those incomes remained at or above pre-pandemic levels (e.g., JobKeeper), people began to spend what they didn't save on goods.

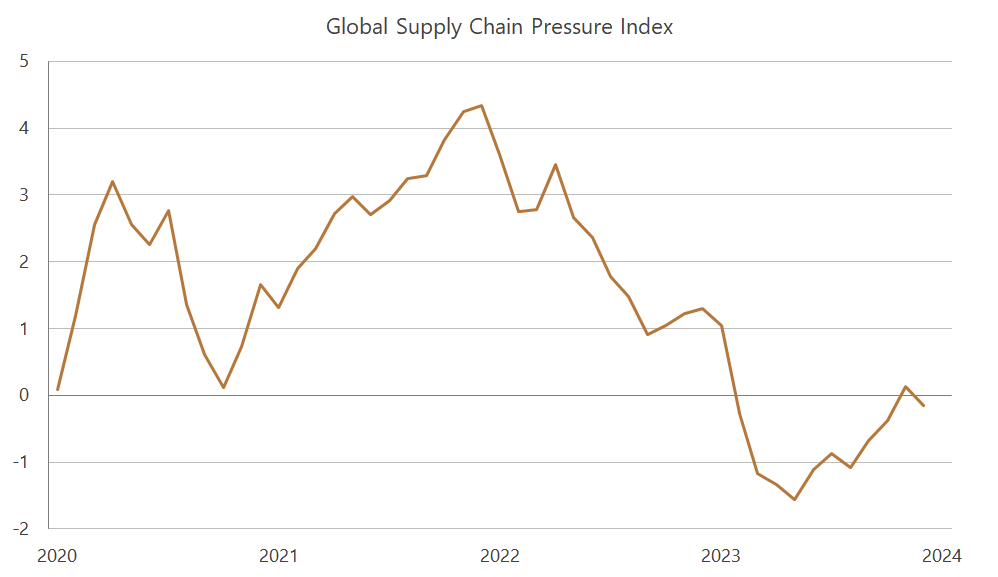

That quickly became a problem because not only was just about every country undergoing the same shift in preferences, but the world's supply chains were hampered by movement restrictions and absenteeism (lots of people got sick!). And when demand outstrips the ability to supply, you end up with shortages and/or higher prices.

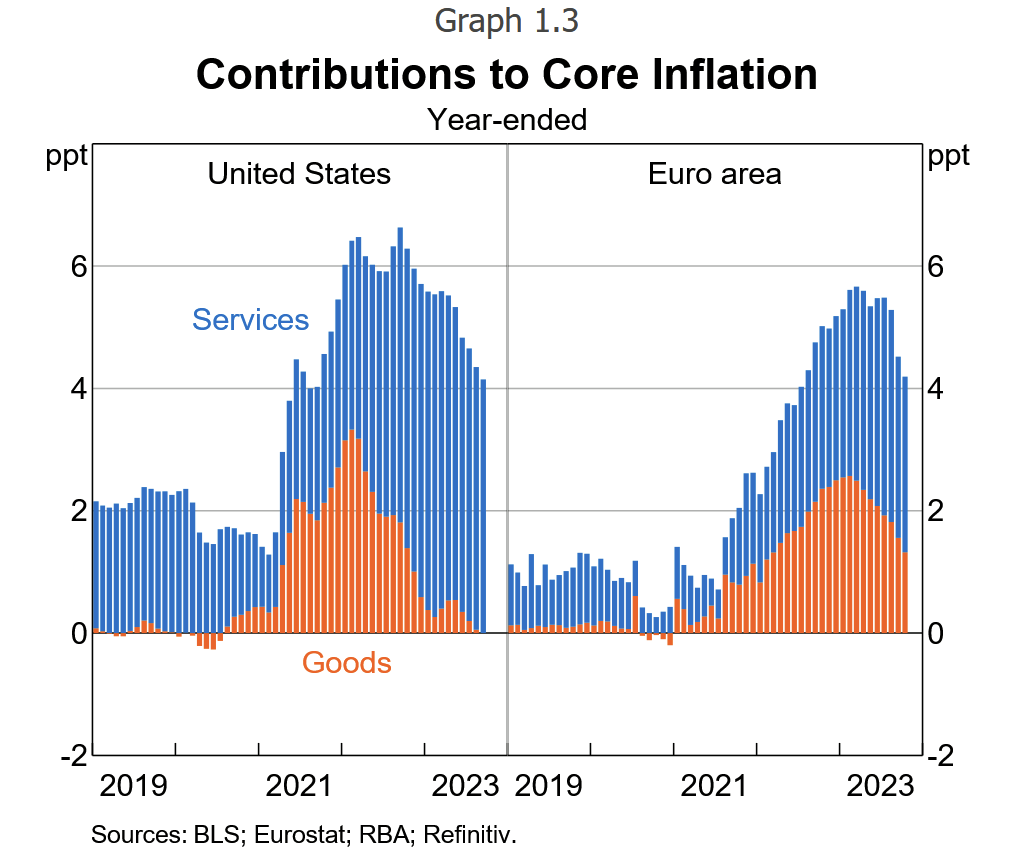

This was just as true in Australia as it was in many other major economies, given that most followed a similar blueprint in response to the pandemic. Fortunately supply chains gradually recovered and goods price inflation receded, helped in part from a shift back to consuming services again as the world reopened, which is where most of the growth in prices is coming from today.

The demand shock

If the inflationary surge was the result of a global supply shock alone – as stated by Treasurer Chalmers, who recently claimed that "[t]he world is inflicting price pressures on Australians and we are doing our best to ease them" – prices should actually decrease once the shock subsides, which according to the US Fed's helpful indicator happened around a year before Chalmers made that statement.

In reality that almost never happens; central bankers tend to prefer 'looking through' the impact of supply shocks, ensuring that – provided inflation expectations remain in check – price growth normalises at a permanently higher level, rather than the pre-shock level. They do this for two main reasons: one, to avoid slowing growth for what is only a temporary shock; and two, to avoid deflation.

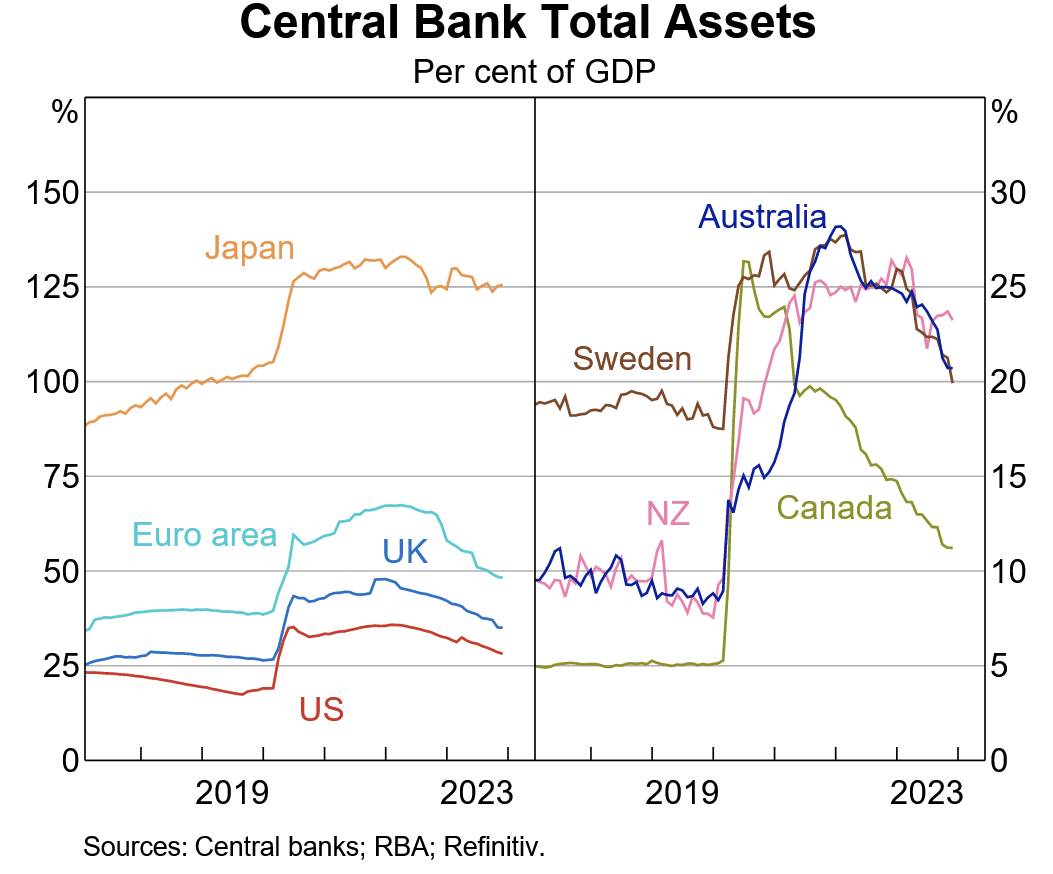

However, problems arise when central banks mistakenly interpret demand shocks as supply shocks, or misjudge the strength of demand, keeping monetary policy too aggressive for too long and allowing for a surge in nominal spending to go unchecked. A quick look at global central bank assets shows just how drastic some of the monetary responses were. Many central banks, including Australia's RBA, were still engaging in quantitative easing (bond buying) well into 2022.

While the jury is still out, this appears to be the most likely source of our current, persistent inflation: global central bankers, almost in unison, underestimated the size and scale of the demand shock, caused by large, unfunded fiscal spending around the world (that is, spending not expected to be offset by future surpluses).

Economist John Cochrane, author of The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level, summarised this effect as follows:

"The standard fiscal theory 101 says that a $5 trillion fiscal blowout will lead to an increase in the price level, to inflate away outstanding debt. But that inflation eventually goes away, even if the Fed does nothing. It goes away a little faster if the Fed raises rates.

...

Is this [slowing inflation] not a victory lap for "team transitory," the view that inflation is just "supply shocks" that go away on their own?

No. A "supply shock" would raise prices temporarily, and then prices would fall back down to normal once the supply shock is over. A supply shock all on its own cannot permanently raise the price level. How is the price level doing?

The cumulative inflation has shifted up the price level by something like 10-20%, depending [on] what you think about the earlier trend. The pure "supply shock" view says that we should now experience a symmetric period of deflation to bring the price level back to where it was, or at least to that plus a 2% trend. The fiscal theory or "demand" view says that this price level shock is permanent, or at least until something else comes along; a fiscal retrenchment would be necessary to lower the price level back to where it was."

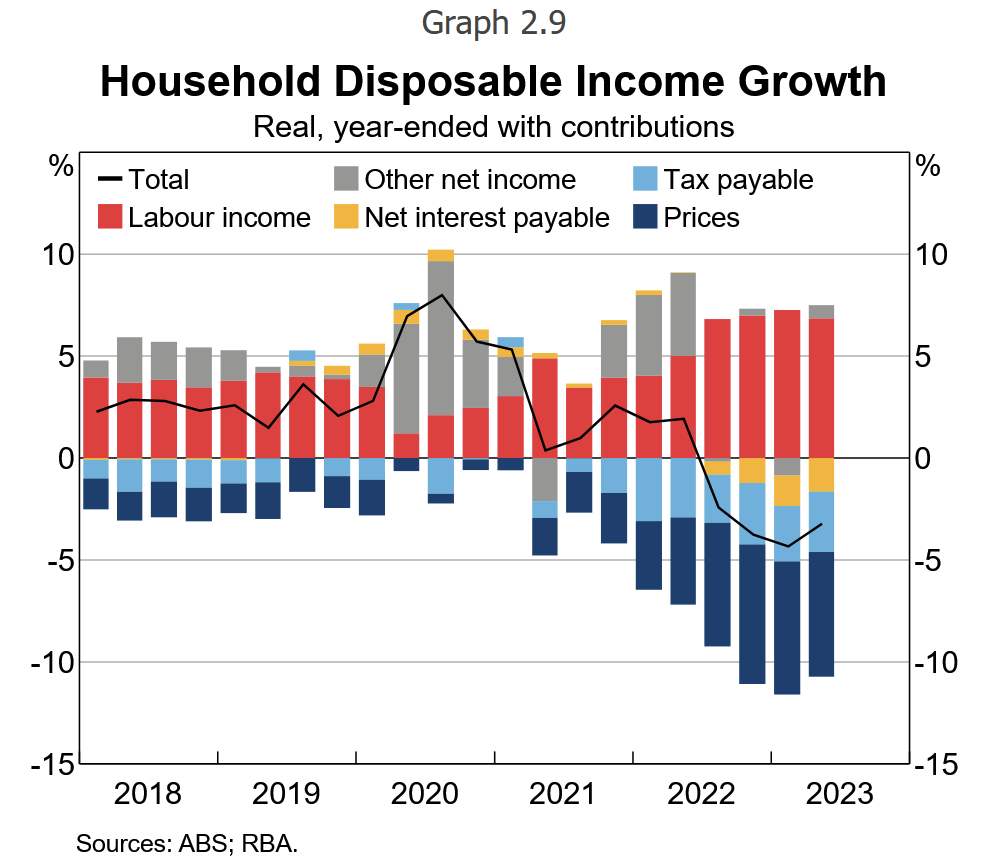

The excess debt our respective governments racked up during the pandemic is still being inflated away and will result in a permanent increase in the price level. The losers are those on fixed incomes, salaried workers and such (the 'employee households', who have been the principal victims of falling real wages (as seen in Graph 2.9 above) and the subsequent cost-of-living crisis – firms are able to raise prices faster than workers can bid up wages.

The good news is that although the increase in the price level is essentially a big, permanent loss of wealth, inflation should gradually come back down to the RBA's 2-3% target so long as the central bank credibly commits to that target. Provided, according to Cochrane, there isn't "some new fiscal or monetary shock [that] will surely intervene":

"That's one of the main dangers of economic forecasting, what I called "unconditional" above. All we can hope to do is to say what is expected to happen, what will happen on average over many situations like our own. But what actually will happen depends primarily on whatever shocks hit us next."

Other explanations

You might have heard stories from certain individuals pointing the finger at migrants or profiteering corporations as the cause of inflation. I'm not going to link to them here or speculate on their possible motivations but will say that there is very little economic support for such claims.

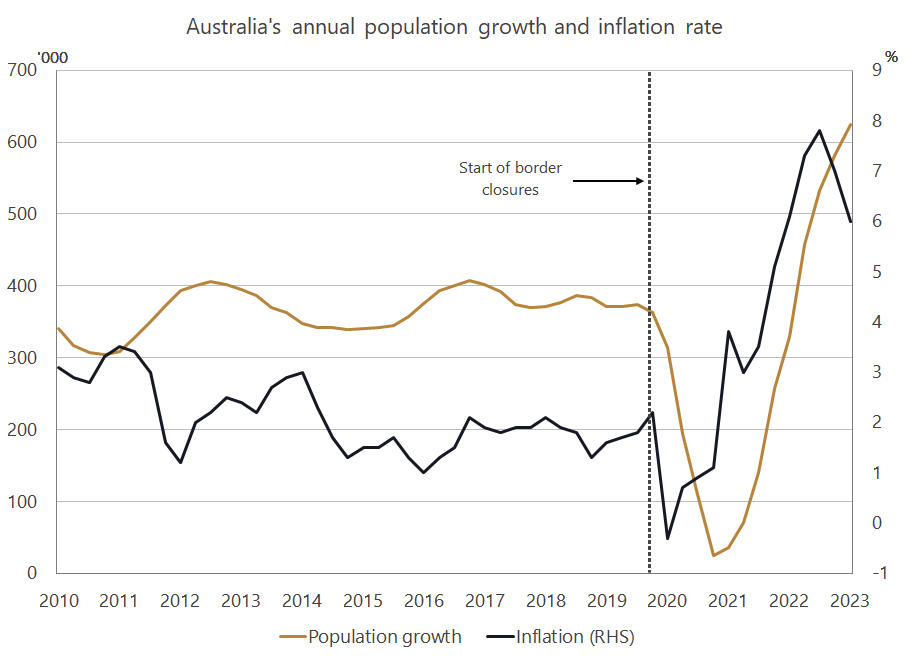

First, migrants. While it's true that Australia took in a record net 518,090 overseas migrants in 2022-23, what matters is the long-run trend and what type of migrants they are. Skilled workers, for instance, will almost certainly produce more than they consume, putting downward pressure on overall prices. Working in the other direction are those on certain temporary visas, e.g., students, who on average are likely to demand more than they produce and therefore contribute to inflation.

But for students, the key is in the word temporary. We spent two years with nearly no student migrant intake, so the large annual increase in migrants is from a low base. The record intake is essentially a supply shock that should be 'looked through': student numbers will gradually normalise, creating offsetting disinflationary forces, and the overall effect on long-run prices will be small to neutral, provided the RBA keeps expectations in check.

Further, inflation had started to accelerate and was rising above 5% annually before population growth had even recovered to its pre-pandemic level.

Which brings me to the second alternative narrative: corporate profiteering. In economics, it's important to ask what changed before trying to establish causation. Did firms suddenly become greedier? Unlikely. Did they suddenly acquire more market power? Slightly more plausible – perhaps enough competitors went out of business – but the change would need to be large to give them the pricing power required to send inflation into the stratosphere.

But what firms did do is pass on the rising costs they encountered from the supply shock discussed earlier, much of which consumers – courtesy of the fiscal demand shock – gobbled up. Without the demand shock, profit maximising firms wouldn't have been able to pass on as much as they did, as higher prices would have reduced the quantity demanded for their products. Instead, they would have passed on only some of the increase and their margins would have declined rather than remain flat, or, in the case of mining – an industry which has virtually no pricing power due to its global nature – increase.

As the RBA concluded in its May 2023 paper on this subject:

"[Firm-level net profit margins are] unlikely to have played a major role in driving the recent rise in aggregate inflation as the widening in margins has been ongoing since 2016 and the increase has been much less pronounced over the past year or so."

Do we need to keep a close eye on the impact of migration (e.g., their effect on housing), and on how competitive our markets are? Absolutely. But while those are important structural concerns, they're almost certainly not what caused the sudden, unexpected rise in inflation and subsequent cost-of-living crisis.

The policy takeaway: don't make it worse

Not much more can be done about inflation – our governments have already spent the money, and global central banks are tightening monetary policy to bring inflation back down to their respective targets.

To ease the cost-of-living crisis in the long run requires fixing the other messes in the economy, from a lack of housing to our non-existent productivity growth stemming from decades without meaningful microeconomic reform. In the near term, the most important thing to do is to avoid making it worse, so I was happy to see that Treasurer Chalmers at least acknowledged that fact in his recent Budget update:

"But I say to every Australian under cost‑of‑living pressure right now, one of the best ways that we can get downward pressure on inflation, which is smashing household budgets, is to provide the kind of responsible economic management, which is a feature of this budget update."

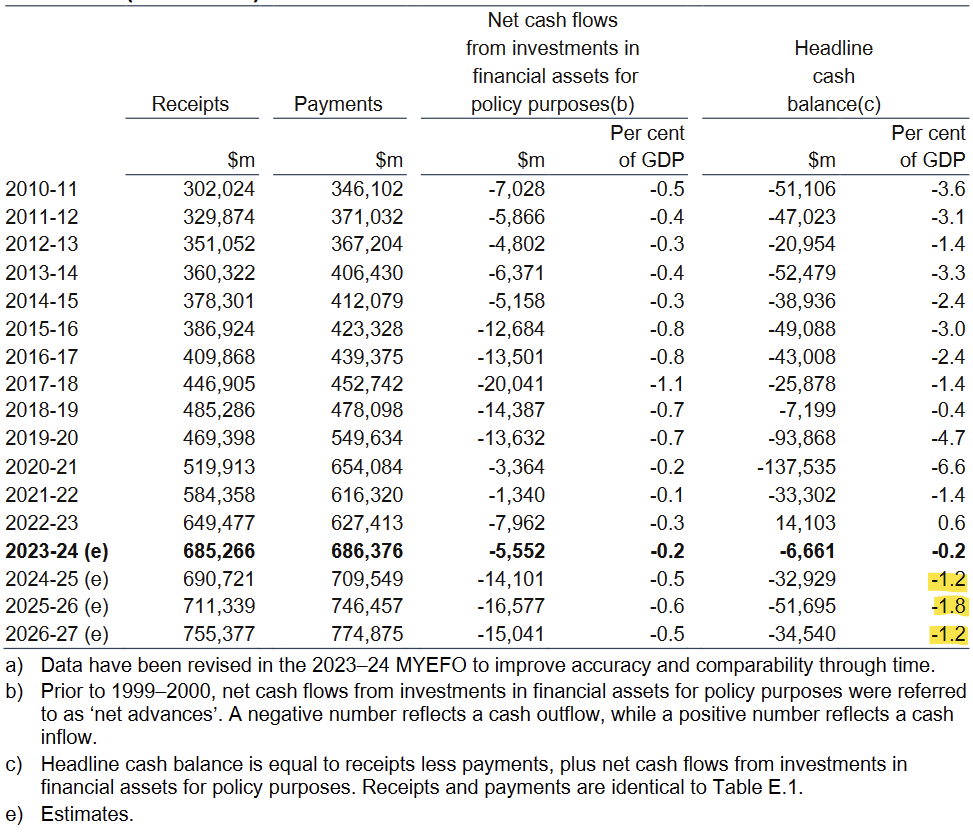

Well said. Unfortunately, actions matter more than words and December's Budget update showed that Chalmers' government intends to follow the LNP's example by spending as if the country is in a permanent recession, rather than one that's growing at over 2% annually with an employment-to-population ratio at a record high.

That kind of spending – payments are expected to increase at a rate of over 5% annually – will delay the return of inflation to the RBA's target and weaken the country's fiscal position ahead of the next (inevitable) shock. The government can use statistical slight of hands to claim it's reducing measured inflation until the cows come home ("The ABS has confirmed that our cost-of-living policies have already reduced inflation by ½ ppt through the year to September"), but if you're still stimulating aggregate demand by running headline cash deficits, then you're making it worse.

By all means, provide transfers to help the most affected groups. But such support needs to be offset by reduced spending or higher taxes elsewhere. If Chalmers is serious about easing the cost-of-living crisis, then the first thing he should do is clean up his own shop – stop stimulating aggregate demand during a demand-driven inflationary cost-of-living crisis!

Member discussion