Friday Fodder (9/24)

The rental affordability crisis has been overblown; why your shower should be a lot better; Chris Minns is doing great work on housing; the freaky side of politics and academia; and a little green bonus.

1. Just how affordable is renting, really?

You may have seen PropTrack's Rental Affordability Report for 2024, which made headlines for all the wrong reasons:

"Rental affordability has hit its worst level in at least 17 years, when records begin... The deterioration in affordability has been driven by the significant increase in rents since the pandemic, which wages have not kept pace with."

No one would deny that rents have increased significantly. But PropTrack's methodology decisions makes the situation look especially bad in times of inflation, and when governments are providing significant support to households.

The first methodological issue is that an "affordable rental" is defined as a listed rental that would require a household to spend less than 25% of their gross income on rents.

This is problematic for two reasons. First, listed rentals only capture what the marginal renter may have to pay. Why may? Because they can negotiate a lower price. All states and territories barring WA (at least to my knowledge) have now banned the practice known as 'rent bidding', where prospective tenants compete against each other for a property. With rent bidding banned, landlords are more likely to list their properties at a high price and be willing to negotiate it down.

This is especially true because of the recent bout of unexpected inflation, which probably left many landlords unsure about what the appropriate price should be; without rental bidding as part of the price discovery process, it's in their interest to start high and then negotiate down. Such behavioural changes using PropTrack's methodology will make rentals look more expensive than they had during the previous editions of this report, even if there was no change to actual rental affordability.

Second, given that the property market in Australia is relatively supply-constrained and vacancies rates are very low, we should expect government support to be captured by landlords. That would make this index look especially bad; for example, the increase to Commonwealth Rent Assistance and various state schemes, while slightly improving affordability for some households, probably caused rental cost inflation to increase.

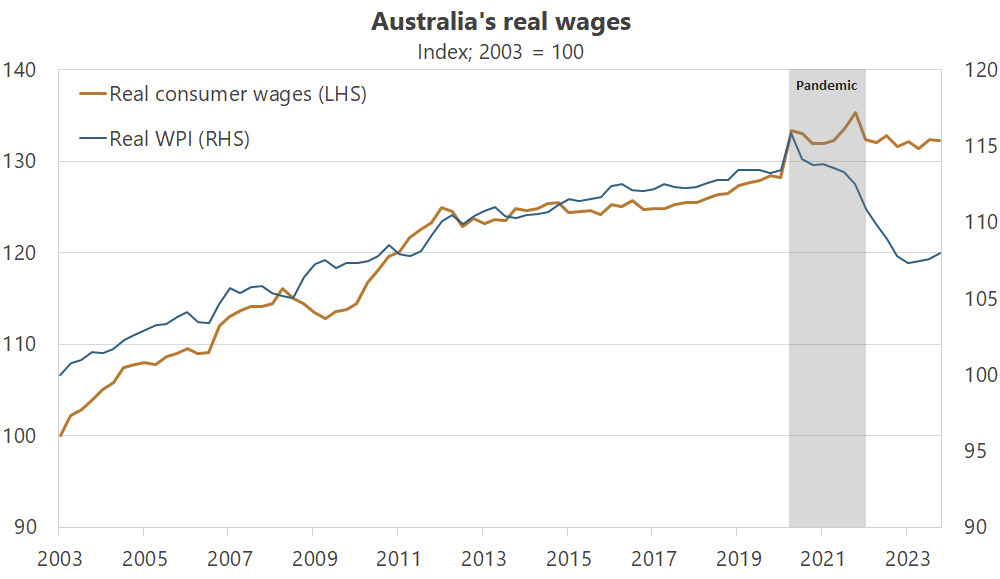

The other methodological decision that makes PropTrack's indicator less than ideal is how it calculates household income, which it does using gross household income from the annual National Accounts and the quarterly Wage Price Index (WPI).

But as I wrote yesterday, the (WPI) isn't a great measure of household incomes during periods of unexpected inflation, because it "has considerable lags, ignores bonuses, and may not fully capture pay increases people might get from switching jobs".

By contrast, the real consumer wage "more closely represents real purchasing power amongst the nation's workers". If we're looking at the affordability of something, we should really be using an indicator that more accurately reflects purchasing power.

In other words, while rentals have been getting more expensive, the situation is nowhere near as bad as PropTrack's indicator suggests, and in fact many renters' incomes (including transfers) have probably grown by even more than rents, meaning the affordability crisis has been overblown.

2. Unintended consequences, shower edition

We're a very dry country, so how we use our scarce supplies of potable water matter a lot. Showers are big users of water, which is why the Plumbing Code of Australia requires that shower heads in all new developments have a maximum flow rate of 9L per minute.

But less water pressure means it takes longer to rinse that shampoo out of your hair, or wash that soap off. What if reducing the flow rate causes us to take longer showers, increasing the amount of water we use? A new paper from the UK found exactly that:

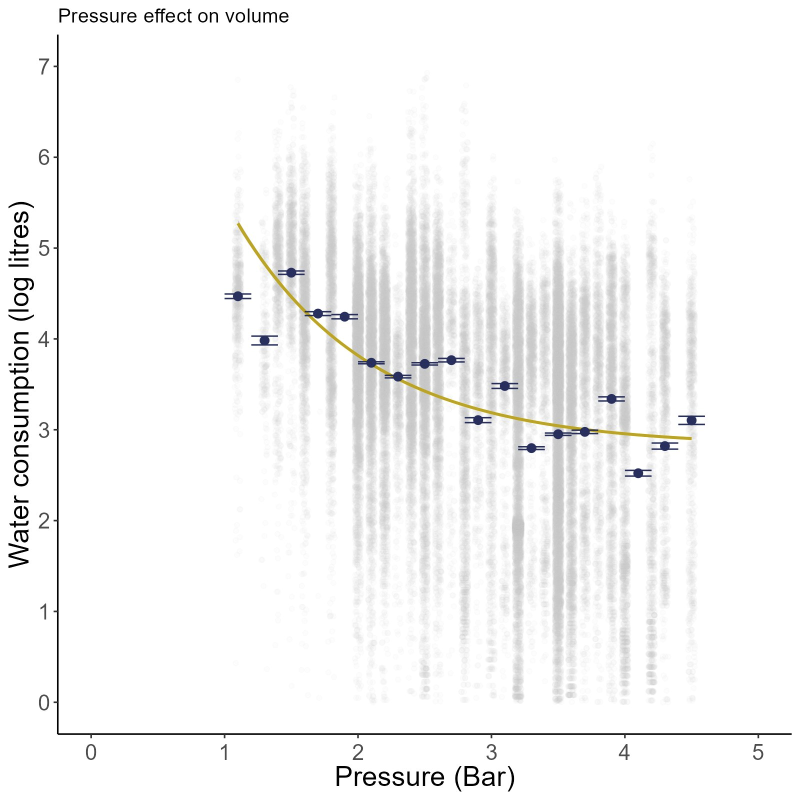

"Water consumption in 290 showers was covertly monitored for 39 weeks, capturing 86,421 showering events. Increased water pressure was strongly associated with reduced water use-an effect that can be amplified even further by installing smart timers to inform users of their shower duration.

No paper would be complete without a cool chart:

A rate of 10 litres a minute equals 1 bar, so Australia's regulated maximum flow rate of 9L per minute puts us right in the upper left, or 'high use' part of the above chart.

Removing our requirements for water restrictors, combined with an information campaign to encourage the use of shower timers, would probably see us use less water overall and help the environment (showers use hot water, so there are also potentially large energy and carbon savings).

3. Chris Minns gets it

I don't often sing the praises of politicians but Chris Minns, Premier of NSW for the past year, was saying a lot of the right stuff in state Parliament this week. Specifically, when asked about his proposed housing reforms that will "accelerate rezoning" around eight transport hubs, Minns said:

"The vast bulk of academic literature in relation to housing supply and demand makes it very clear that housing supply is directly related to the costs of both the purchase price and the rent paid by consumers in the private market... The Grattan Institute, the NSW Treasury, the Commonwealth Reserve Bank, the Productivity Commission—every reputable economist and land economist in Australia recognises the correlation between housing supply and eventual price.

...

When we were in opposition, members opposite would say, 'Look at the cranes in the sky'. Now, any member who meets with a property developer or a builder has a dirtiness associated with them in some way. Members can look to the vast majority of economists and academics in New South Wales, who clearly and repeatedly recognise the connection between supply and price, or they can follow the member for Wahroonga. They cannot do both."

I'm no fan of appeals to authority, but I get that's how politics works (read #4 today for more on that!). However, in this case Minns is on the right side of the debate – what's needed to solve the housing crisis in this country is more responsive supply, which means a less rigid zoning regime.

Minns is also correct that without meaningful change, people will eventually start to leave Sydney for more affordable regions, which is what an influential 2018 paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives also found:

"When housing supply is highly regulated in a certain metropolitan area, housing prices are higher and population growth is smaller relative to the level of demand."

That paper also touched on the political economy of deregulating supply, a hurdle Minns has yet to fully clear:

"The great challenge facing attempts to loosen local housing restrictions is that existing homeowners do not want more affordable homes: they want the value of their asset to cost more, not less. They also may not like the idea that new housing will bring in more people, including those from different socioeconomic groups.

...

This suggests that more fiscal resources will be needed to convince local residents to bear the costs arising from new development. On pure efficiency grounds, one could argue that the federal government should provide such resources, but from a political economy perspective, the median taxpayer in the nation effectively transferring resources to much wealthier residents of metropolitan areas... seems challenging to say the least. However daunting the task, the potential benefits look to be large enough that economists and policymakers should keep trying to devise a workable policy intervention."

If the Liberal Party's attacks in Parliament are anything to go by, including joining the Greens in bashing property developers (hint: they're not to blame), then Minns certainly has his work cut out for him!

4. Politics and academics may be freakier than you think

Steven Levitt, the co-author of 2005's pop-econ best seller Freakonomics, retired from his tenured job at the University of Chicago at the young age of 57. He's now speaking quite freely, with a recent podcast discussing his retirement a real eye-opener.

On public policy

"It took me years and years to understand that, number one, usually nobody cares at all about your research. No matter how much you love it, it never gets any attention. Number two, the quality of my research had nothing to do with it being passed around. It was being passed around Washington because it was the only paper that supported the position that they had already chosen. Right, the policy outcome they want chosen first and then they went for papers. And I'm sure they were disappointed that the only article they could find that it all supported them was by some grad student, but they took what they could. And what I read, the real lesson I learned over time is that I don't actually think that my research or even my writing, more popular writing, has ever really fundamentally changed the way any politician thought about anything and that it's just, I've come to a different conclusion which is that it is incredibly hard to influence any policy or anyone's beliefs by doing research."

On quitting academia

"So, these were four papers that I was really excited about and collectively they had zero impact. They didn't publish well by and large, nobody cared about them and I remember looking at one point at the citations and seeing that collectively they had six citations. I thought, my god, what am I doing? I just spent the last two years of my life and nobody cares about it. And I really think it's true that the way I approached economic problems, without a fashion, without a vogue, and for better or worse, probably the profession is better for having a different set of standards than I was used to meeting up with. And that was really discouraging to me.

...

It just didn't make sense to me to keep on puttering around, doing all this work, spending years to write papers that no one cared about when I had other ways of getting my ideas out. And really my interests were elsewhere. I didn't get any thrill. It'd be one thing if I got a thrill from publishing, if I loved the act of publishing, and it made me feel great to see my nature in some journal, then it would be different. But I never cared about that. I just liked answering the problems and I realised there were better ways, there were better venues for me to answer your problem. And so really the question is, why am I retiring now? The question I should ask myself is why didn't I retire a long time ago? It made no sense. I've just been, I've thought, I've known for years, it's the wrong place for me to be. And it just took me a long time to figure out how to extricate myself from academics."

On Nobel prize winner James Heckman

"An absolute genius, but a nightmare personality. He eventually decided that he and I were at war for the future of economics although I never saw it that way. And he did crazy things. I just tell you one crazy thing he did. At one point he started a new seminar series. So, an academic department to have the labour economic series, the macro-exemplary. He started a new seminar, and I'm not even joking. I'm literally telling you the truth. It was called the 'Get Out the Sleaze' seminar. And the only thing you needed to be invited to speak was to be critical of me. So, it was an entire semester of some academics, a lot, some of them weren't even academic. You didn't have to be an academic. You just had to not like me and have publicly said you don't like me. And he invited, he invited guest after guest whose only agenda was to destroy me to come on campus to present their work.

...

I didn't, it didn't bother me that much because I didn't take it that seriously, but the extent, the extremes that he would go to try to make life difficult, not just for me, but for others, really, it's stunning. And you could never, in a business world, you just couldn't get away with that. But in academics, there's enough freedom that people can just do really anti-social things. And so, still get away with it."

You can listen to the full podcast here, or read the transcript here.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

A public property developer won't fix housing – The Greens' plan for a public property developer to build below-market housing won't fix the housing crisis. It ignores market realities and could crowd out private investment while driving up construction costs.

What Australia's per capita recession really means – Australia faces deepening per capita recession amid lack of productivity-boosting reforms. Excessive pandemic stimulus fuelled inflation, while ballooning government spending propped up growth amidst a struggling private sector. The risk going forward is a period of stagflation (low growth, elevated inflation) and there's no China-led commodity boom on the horizon to rescue us this time around.

6. And a bonus: hypocrisy thy name is Greens

Given how critical I was of the Greens' housing policy, why not layer it on extra thick this week? It turns out Greens leader Adam Bandt, whose website claims he is fighting for "a safe climate, a more equal society and a real future, for all of us", lives a life that most of us could only dream of:

"Greens leader Adam Bandt has come under fire for racking up an expenses bill of almost $1million a year, including hundreds of thousands on printing and two private jet flights.

The anti-fossil fuel campaigner also claimed $12,000 on a taxpayer-provided vehicle and petrol allowance plus $29,000 on government COMCAR trips and taxis, according to figures from the Department of Finance.

Despite his party's core policy of cutting C02 emissions Mr Bandt used two private jets during the 2022 election campaign, landing tax payers with the $23,000 bill.

...

The $963,166 in expenses racked up by Mr Bandt are on top of his $314,000 salary and do not include the wages of his personal staff."

Rules for thee, not for me! Have a great weekend.