Cutting migration won't solve the housing crisis

I tend to write a lot about Albanese and Chalmers, but only because they're the ones in government making the policy decisions. Fortunately, it appears that the Coalition has finally awoken from its policy slumber, with opposition leader Peter Dutton revealing that if elected, his government would 'fix' housing by:

- cutting the permanent migration program from 185,000 to 140,000/year for two years (-25%), then transition it back up to 160,000/year over another two years;

- temporarily banning foreign investors and temporary residents buying existing homes for two years; and

- reducing excessive numbers of foreign students studying at metropolitan universities.

On the latter point no details were provided, other than that he "will work with universities to set a cap on foreign students". Given that the current government is already doing something quite similar – it plans to 'soft cap' international student numbers, with education providers able to get around it by constructing "purpose-built accommodations" – it's not yet clear how, or even if, Dutton's student policy will be different.

But outside of the ambiguity on the question of students, Dutton claimed that all said and done these policies would "free up almost 40,000 additional homes in the first year. And well over 100,000 homes in the next five years".

Sounds good. But just how realistic are those claims?

By the numbers

At the end of June 2022, Australia had a total dwelling stock of roughly 10.88 million. We've added around 230,000 more since then (completions minus demolitions), bringing the stock to about 10.92 million.

So, by cutting permanent migration Dutton will increase the stock of homes by about 0.4% in the first year and 0.9% over five years. As a rule of thumb, a 1% increase in the supply of housing in Australia reduces the cost by 2.5%, so house prices will be around 2.5% cheaper after five years under Dutton's plan.

Of course, every bit matters, but that's hardly the solution to a crisis.

There's also reason to doubt the numbers will even be that large. Dutton's plan is to cut permanent migration by 45,000, and he expects that will make 40,000 additional homes available. He didn't show his workings, but the only way I can make sense of that is to think he assumed:

- almost all of those permanent migrants will live alone (1.13 to a home versus the Australian average of 2.49); and

- none of the people gaining permanent residency in the next year are in Australia.

On the second point, each year 60% of the people gaining permanent residency are in Australia when it's granted, because many of them transition from temporary visas. Those people will already be renting or own a home, so shouldn't be included in Dutton's estimate of "freed up" homes.

If I re-run the estimate above but exclude those 60%, then Dutton's plan will, at best (there are almost certainly more than 1.13 migrants per dwelling), reduce dwelling costs by 0.1% in the first year and around 0.4% after five years.

As for banning foreign purchases, that's likely to be even smaller in terms of market impact. Just 1,339 foreign approvals were granted to purchase an established residential dwelling in 2021-22, and the current government is hiking taxes on any of them that are left vacant for more than six months. In other words, either the government will get a lot more cash it can use to build dwellings or subsidise rents, or those foreign-bought homes will be occupied.

Again, it's not nothing. But it's small, and messing with migration is generally a bad way to deal with a housing crisis that is the result of many years of completely unrelated but equally poor policy.

Migrants aren't the reason the housing market is messed up

Permanent migrants – the stream Dutton wants to cut – are only expected to make up around 17% of net migration in 2024-25. If you're looking to blame migrants for using too much housing, it's the temporary stream – e.g., students, working holiday makers – where you should cast your gaze. And there's no denying that the large influx of students following the border re-opening has contributed, at the margin, to a tighter housing market.

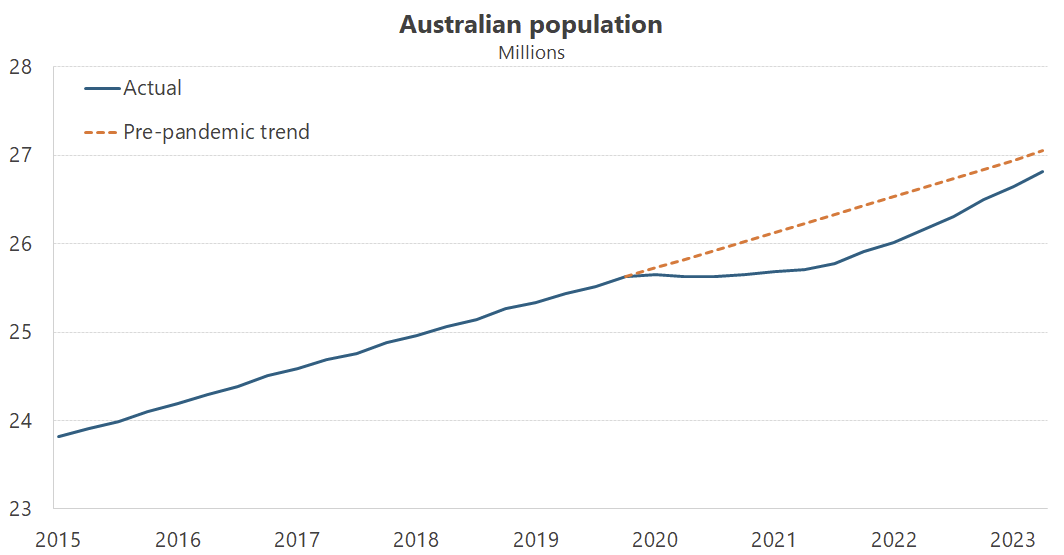

But the housing market is no worse than it would have been without the pandemic; our population is actually lower than it would have been had the pre-pandemic trend continued.

We may not ever reach the pre-pandemic trend, either, because the recent surge in net migration is temporary; students and backpackers couldn't get into the country for a couple of years. During those years, existing visa holders left but no one came in to replace them. Now the reverse is happening, with new temporary visa holders coming in each year but no departures to offset their arrival. The vast majority of students finish their degrees and then go home, and many will soon start doing that again.

And you really don't want to be making changes to long-term policies such as migration to temporary phenomena that will reverse once the people granted visas in 2022 begin to leave. Especially as migrants aren't that impactful on housing prices, at least compared to other factors, as "an immigrant inflow of 1% of a postcode's population raises housing prices by around 0.9% per year".

The fact is, changes to migration policy are unlikely to have much impact on the housing market, with variables such as interest rates, investor demand and taxes far more important for prices. If we want to fix housing, there are plenty of policy levers we can pull, but a knee jerk change to migration is unlikely to be a very effective one.

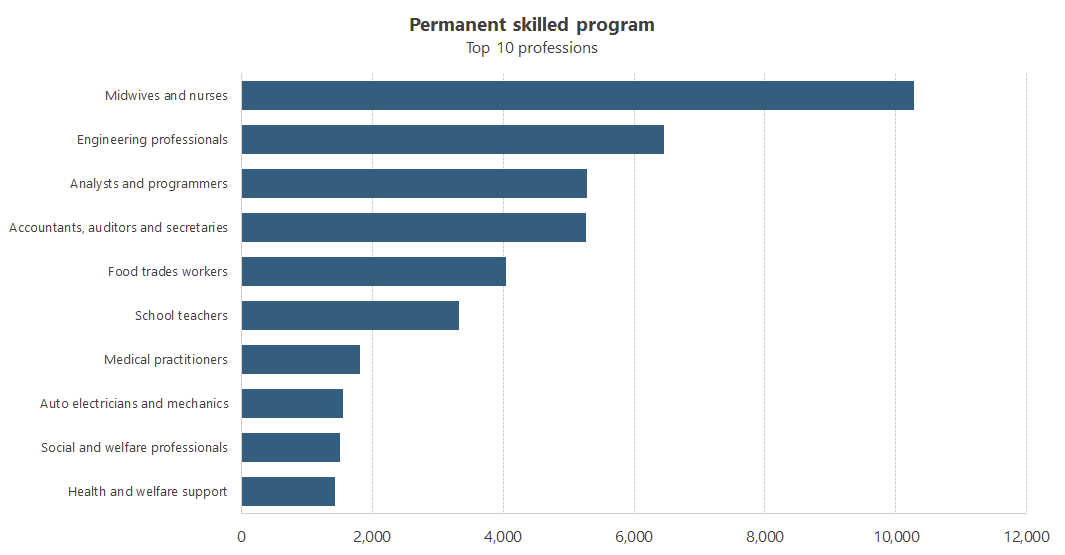

Reducing permanent migration could also be counterproductive, because it would cut off supply of the very people we need to build more dwellings and perform other tasks we value, such as caring for us:

As for reducing temporary visa numbers, having the government centrally plan student allocations by education provider may also come with unintended consequences, as ANU's Andrew Norton cautioned when the Albanese government's policy was announced:

"The caps will face all the problems I have identified with bureaucratic allocation of domestic student funding. Because numbers will be allocated between universities and courses according to a politician or bureaucrat’s view of where students should enrol, rather than where students want to enrol, actual enrolments are likely to be well below the capped level."

Look, you won't find any Australian who disagrees that the housing market is messed up. But without a doubt, most of them – including many of our politicians – have the wrong idea about how to fix it.

More populism than substance

If migrants aren't to blame for the bulk of our housing woes, why is Peter Dutton making migration the centrepiece of his "housing" plan? One word: populism. Migration is a political hot potato right now, with the media regularly producing articles showing record rates of net migration, often omitting the fact that it's temporary and will soon revert back to something resembling the pre-pandemic period (perhaps even lower with the recent crackdown).

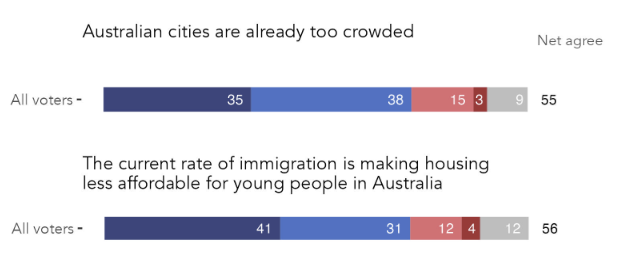

A Redbridge poll from April this year found that most voters believe that our cities – which have some of the lowest densities in the world – are too crowded, and that the current level of migration is making housing less affordable.

One Nation, led by infamous anti-migration campaigner Pauline Hanson, is surging in the polls, from 2.5% to 6% – the highest level of support for the party for six months since November 2023".

One Nation is closely aligned to the Coalition on most other policies, so Dutton is moving further towards nativism to convince marginal Liberal party voters to stay with the party. It's a similar strategy to the one the Labor government recently adopted when it reformed HECS in an attempt to keep some progressive, inner city votes from switching to the Greens.

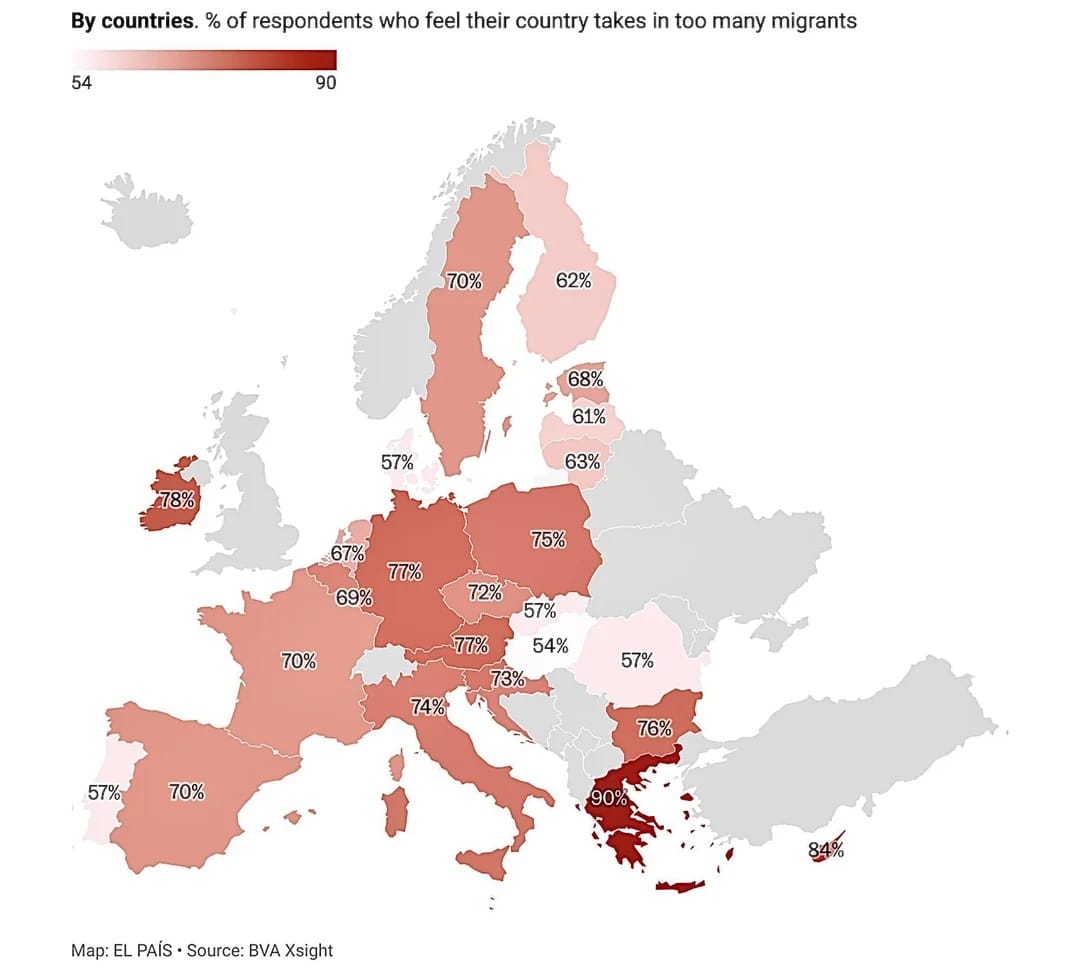

It's a sad state of affairs that our economic policies are being determined by fringe parties on extreme left and right, but that's politics, I guess. And we're not exactly alone: the new Dutch coalition wants to opt out of European Union (EU) rules and cap asylum seeker and foreign student numbers. Support for migration across Europe is uniformly poor, making opposing it a political winner:

Even the EU itself, once very pro-migration, now has a new "migration pact", which will see it establish detention centres and strengthen its border control.

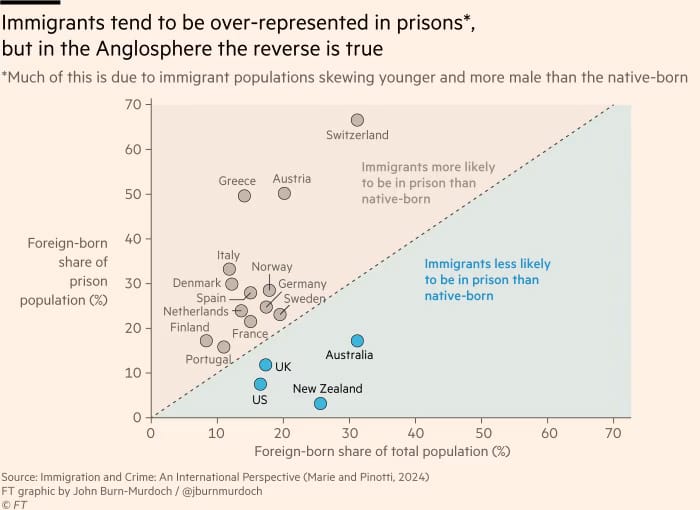

We in Australia talk a lot about "migration", but not all migration is the same. Australia and the other Anglo's have done quite well in the past, which is perhaps one reason why we sit near the bottom of this chart:

European nations, which have taken in far more migrants that are low skill, male, and often don't speak English, have done much worse out of migration than Australia. For example, in Denmark "at no point in their life-cycle is a MENA (Middle Eastern, North African, Pakistani or Turkish) immigrant a net contributor to the public finances".

Finding the right balance

Don't get me wrong; Dutton's solution will, all else equal, slightly reduce house prices. But in the long run, declining birth rates and fewer migrants will move us in the direction of Japan, where houses are literally being abandoned – especially in the regions – because there just aren't enough young people willing to live out there anymore.

That may well be what the voters want. But there are limits to nativism; Japan, for example, recently doubled its annual skilled migrant cap "based on expected labour shortages in certain industries even if employers were to raise wages and make other changes to attract talent".

If you have low birth rates and low migration, real GDP will slow or even contract, until eventually you can't afford the various entitlement programs you've promised yourself. That's also a difficult political decision but is probably far enough in the future that it's a trade-off most voters aren't even considering.

Ultimately, it's a shame that both major parties are scapegoating migrants as the cause of the housing crisis, instead of looking at their own policies – for example, the various taxes and welfare thresholds that keep the elderly in oversized houses, gobbling up scarce housing supply. By all means we should have a serious conversation about the appropriate amount and types of migration, but blaming them for the housing crisis is just pure politics.

But perhaps that's inevitable when at its core, most people don't understand the housing market, and will often vote against their own interests when it comes to housing. Dutton and Albanese are just doing their jobs, playing into anti-migration sentiment for political gain, even if it comes with significant costs.

Member discussion