What's up with Japan?

If you've found yourself dreaming of a holiday lately, you've probably stumbled across an article or two on Japan. That's because Australians are reportedly flocking to the land of the rising sun in record numbers:

"The number of Australians heading to Japan is going through the roof, with 252,900 people from Down Under heading to the Asian hotspot between January and March this year - up 46.3 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019."

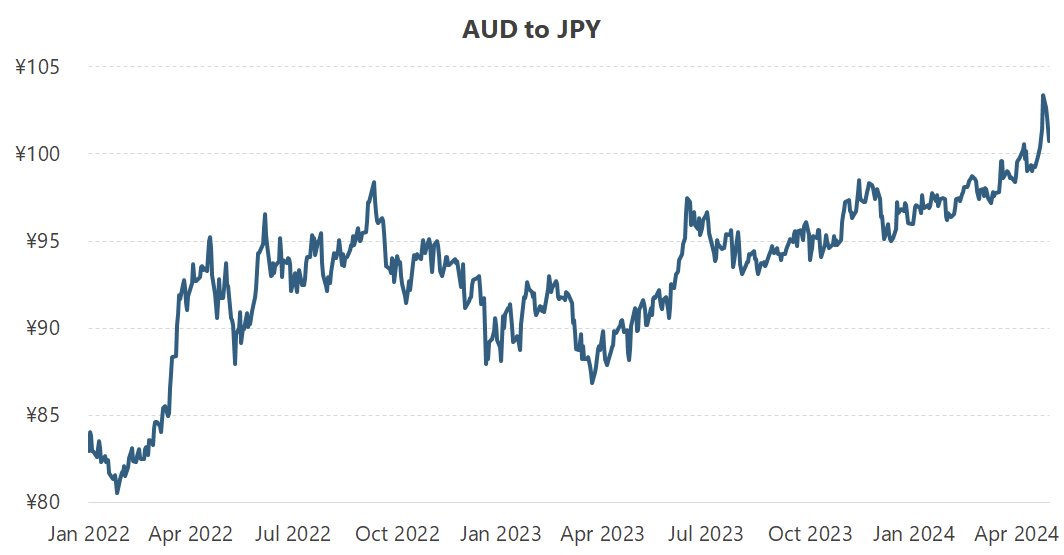

One of the reasons cited for the surge in tourist numbers is the collapse in the value of the yen. Even against the woeful Aussie dollar, the yen has performed poorly in recent years; since the start of 2022, it has lost over 20% of its value and is now below parity (1 yen to 1 cent) for the first time in a decade.

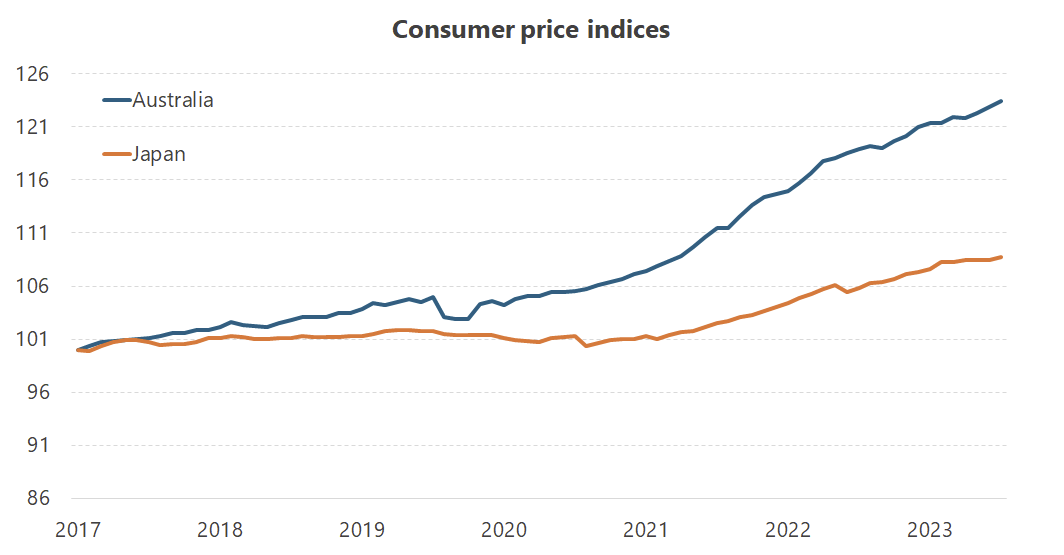

Now it's true that a relatively weak currency, provided domestic prices haven't risen by even more, makes for a great excuse for a holiday. And that's exactly what has happened: not only is the Aussie dollar stronger than the Japanese yen, but domestic prices in Japan have risen considerably more slowly than they have Down Under (i.e. the real effective exchange rate has declined).

For an Australian in Japan, their dollar now goes a lot further than it did only a couple of years ago, notwithstanding a few foreigner-only surcharges the Japanese have started to tack onto everything from hotels to trains in a bid to level the playing field between locals and tourists:

"A dual-pricing system is emerging as a solution to this issue. Under the system, prices and fees are set high for foreign visitors so as to increase sales and profit, maintain local infrastructure, and hold demand in check, while affordable prices are kept for Japanese people."

But despite the sensationalist headlines about the "staggering" increase in tourism over the past year, we shouldn't get too far ahead of ourselves. In the decade prior to the pandemic, Australian peak-season tourism (Dec/Jan) to Japan was growing at an annual growth rate of more than 20%. The 2023-24 increase has been impressive, but tourist numbers are still below the pre-pandemic trend.

I would have thought the relative collapse in the yen would have sparked a few even more trips than what we've seen. But there are also plenty of reasons why Aussies might not be all that quick to jump on a plane despite Japan's affordability, whether it be our own cost-of-living crisis, limited flight options, or because most people like to plan their holidays well in advance and the yen's collapse against the Aussie dollar only really started in 2024 (the AUD/JPY exchange rate was largely unchanged between Jun 2023 – Jan 2024).

But tourism aside, I wanted to know a bit more about what's up with Japan's economy and why the yen has collapsed in recent months, and whether it's likely to stay depressed.

Will Japan have a debt crisis?

There has been chatter lately about whether the yen's collapse is the precursor to a currency or, worse, full-blown financial crisis in Japan. For example, Noah Smith:

"Japan is no emerging market — it's one of the world's largest economies. A Japanese economic collapse wouldn't just impoverish the people of Japan; it would shake one of the pillars of the global economy, causing negative ripple effects in the Western financial system and major headaches for Western companies. Sudden Japanese weakness would also alter the geopolitical balance of power in Asia, potentially bringing us closer to a major war.

The possibility that Japan could have an emerging market-style currency crisis should therefore be concerning to people all over the world. It's a macroeconomic event that deserves our attention."

People have been warning about a looming Japanese currency and/or financial crisis ever since the last bubble burst in 1990, when a collapse in private credit was largely absorbed by the public sector. Today, the Japanese government's net debt-to-GDP leads the developed world at 155%, and its central bank has been so active in 'quantitative easing' that it owns over half of all Japanese government bonds on issue. The situation looks precarious, to say the least.

But Japan's government has been leading the world in terms of indebtedness for decades. There is, of course, a point at which net debt reaches levels so high that markets begin to doubt whether the government will pay it back. But it's not clear Japan is at that point yet (although Greece wasn't at that point either... until it was).

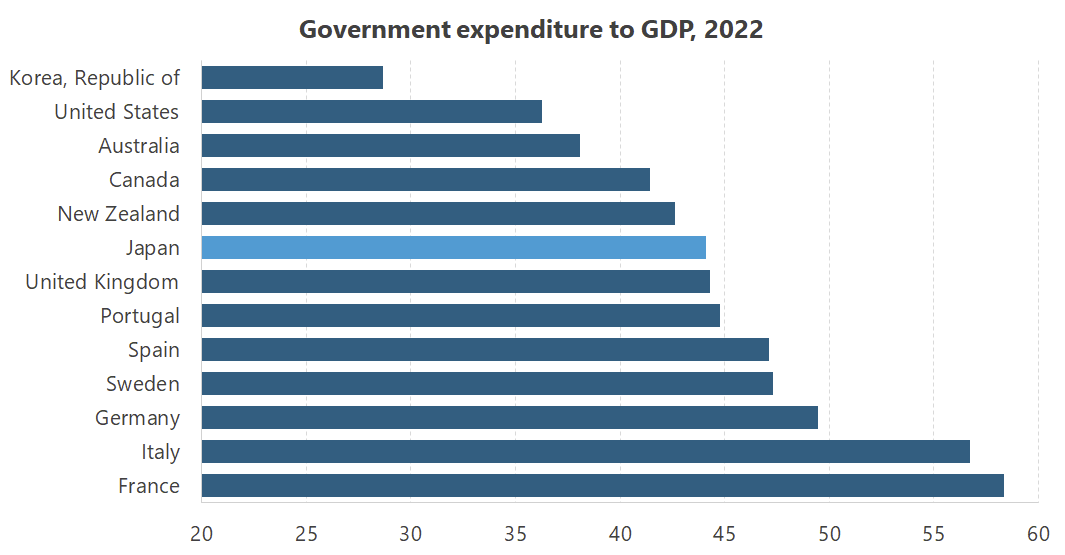

There are a few reasons why Japan's public debt is probably still manageable. First, if we take the same group of countries we did earlier, Japan's public expenditure to GDP is in the middle of the pack; i.e., it isn't anything to be especially worried about, at least in the context of a debt crisis (I'd be more concerned about Italy). Japan still has the fiscal capacity to raise taxes.

Second, Japan's natural interest rate is probably lower than most other advanced economies because its potential growth is lower. While Japan doesn't have a productivity problem any more than other advanced economies – per working-age adult, Japan's post-1990 GDP growth has actually performed as well as the US – it does have an ageing problem.

Basically, it doesn't have enough young people; its ability to produce workers to pay for its government's spending has been declining for decades, both due to low fertility rates but also its unwillingness to permit much immigration, relative to countries such as the US, Canada and Australia (Joe Biden gaffed on the weekend, accusing Japan of being "xenophobic. They don't want immigrants.").

But the lower potential rates of growth and nominal interest reduces the burden of Japan's debt. As a share of GDP, government interest payments in the US are roughly double Japan's, despite its lower share of debt to GDP.

Third, Japan has its own currency (unlike, say, Italy). Notwithstanding the Bank of Japan's (BOJ) interventions, it has an open capital account and so its floating exchange rate moves in-line with its trade in goods and services and capital flows. The yen could collapse reflecting changes in those flows, but Japan won't have a currency crisis unless investors believe that the only way it'll be able to repay its debt is via inflation, rather than through spending cuts or revenue raising.

It's just not clear at all that concerns about a crisis are what's causing the yen's decline, given that Japan's public debt burden is still below many other advanced economies and that it has more fiscal manoeuvrability than most European countries. What seems more likely is that the yen is falling because of changes to trade and capital flows.

Caught between a rock and a hard place

Japan has changed a lot over the past few decades. Domestic labour constraints and the emergence of countries such as China and Vietnam as manufacturing options led corporate Japan to conduct " a strategic relocation of their production bases by expanding their overseas production of low-end products, while domestic production is concentrated more on high-end products".

Japan is still a big investor and goods manufacturer but a lot of that now takes place offshore. That insulates corporate Japan somewhat from exchange rate movements, so a weaker yen is not as effective as it once was in terms of boosting Japanese exports, but it is effective in boosting corporate profitability. Even with the yen's 16% depreciation against the US dollar since the start of 2023, Japan's Nikkei index is up 28% in US dollar terms over the same period (nearly 50% in yen terms).

I think what a lot of commentators forget is this isn't the first time the yen has fallen a lot; it's not even the biggest depreciation in recent memory. In 2012, after Shinzo Abe became Prime Minister and commenced 'Abenomics', the yen depreciated nearly 40% against the US dollar in under two years – yet no currency crisis ensued. In the past two years, the yen has 'only' lost 18% of its value. True, they were starting at different levels (100 yen was worth ~75c in 2012), but these kinds of movements are not unusual for floating currencies. Following the mining boom/bust from 2013-15, the Aussie dollar went through a bigger depreciation than Japan is facing today, and we turned out just fine.

The BOJ has over a trillion US dollars in reserve – which it accumulated during the decades of trying to reduce the value of the yen – and while those may not last long if confidence in the yen were to collapse, that doesn't seem likely. While the BOJ will inevitably burn some of those reserves trying to slow the decline in the yen, it's ultimately pushing against a string: the difference between yields overseas and in Japan has widened since other central banks started tightening monetary policy in 2022/23, and that's what's causing the yen to depreciate. You can't stop those forces with currency market intervention alone.

No, the only way the BOJ can stop the yen's depreciation is by closing the monetary policy differential (ideally with fiscal support – Japan's government is still running a budget deficit of around 5% of GDP). But it seems more than content, perhaps because of political pressures, to instead waste its reserves defending some arbitrary exchange rate, perhaps holding out until the US Fed cuts rates – although it could be waiting for quite a while!

Making matters more difficult for the BOJ is that the yen's depreciation may be somewhat self-reinforcing: Japan imports almost all its fuel, so energy costs are going to rise for domestic businesses, reducing their already-low returns, further discouraging repatriation into the yen. Households will find themselves with even less disposable income, reducing domestic demand. Meaningfully tightening monetary policy in such an environment will be painful, and potentially politically unpalatable, given it would also raise the governments interest payments.

Ivory tower mismanagement

Just because I don't think Japan will have a currency crisis doesn't mean I'm optimistic about Japan's economy. A fantastic place for a holiday, sure, but it clearly has an unsustainable debt problem that needs to be repaired (which will further sap private sector growth), is a country where real wages haven't risen for a decade and has chronic labour shortages due to its aging population. It is now much more profitable for corporate Japan to invest offshore than domestically ("ordinary profits" include net interest income, "operating profits" do not), and they're not even sending the proceeds back to Japan anymore.

There just aren't as many exciting, profitable investment opportunities in Japan as there are elsewhere, reducing demand for the yen (outside of tourism). The yen is weak because Japan's economy is weak.

But it's important to remember that none of these problems are new; they've just been exposed by the rise of inflation and interest rates across much of the world. According to CLSA's Nicholas Smith, domestic demand is likely to stay subdued no matter what the BOJ does:

"Pensioners account for 39 per cent of consumption and their payouts likely won't stay up with such an inflation bump. [The BOJ's target of] 2 per cent inflation target makes more sense in ivory tower theory than in an economy that hasn't seen inflation in a generation."

There's very little fiscal or monetary policy can do to address changes in demographics. Japan's government and central bank did everything they could to stimulate domestic demand but their attempts were futile. Leaders of an aging, relatively high-saving country such as Japan should have acknowledged that real GDP growth was virtually impossible and simply tolerated mild deflation. They should have conceded that various spending and entitlement programmes that the Boomer generation promised itself were no longer affordable.

Instead, the government's deficit spending and the BOJ's efforts to stimulate domestic demand have left it with debts that the Japanese will be paying for many years to come. As a result, the Japanese people will be poorer, and some of that will be reflected in a weaker real effective exchange rate.

Member discussion